Bugonia: A Tale of Two Yorgos

Inside the edit of Lanthimos’ closest collaborator (not Emma Stone)

Hi everyone —

Hope your year is off to a great start.

We’re hard at work at Eddie on some new cool stuff we’ve been dreaming about for a few years, now ripe to bring it into fruition.

It’s a special time we live in. I am grateful for the chance to dream and then chip everyday at bringing that dream into reality.

I know you’re doing the same and working towards your big dreams.

Enjoy today’s newsletter. Happy Friday! And have a great weekend.

—Shamir

CEO/co-founder

Eddie AI, the assistant video editor for pros

Quick note: If you haven’t watched Bugonia yet, go watch it now. I’m about to spoil the entire thing. You’ve been warned.

Three months after its release, Bugonia is doing exactly what a Lanthimos film does during awards season: making people uncomfortable and starting arguments. Emma Stone’s actual shaved head became a meme. Jesse Plemons with his bee-obsessed conspiracy theorist who kidnaps a pharmaceutical CEO (Stone) because he believes she’s an alien from Andromeda.

The film has since generated think pieces about the validity of modern conspiracy theories and whether we’re supposed to sympathize with him.

But the person who actually made this film work is Yorgos.

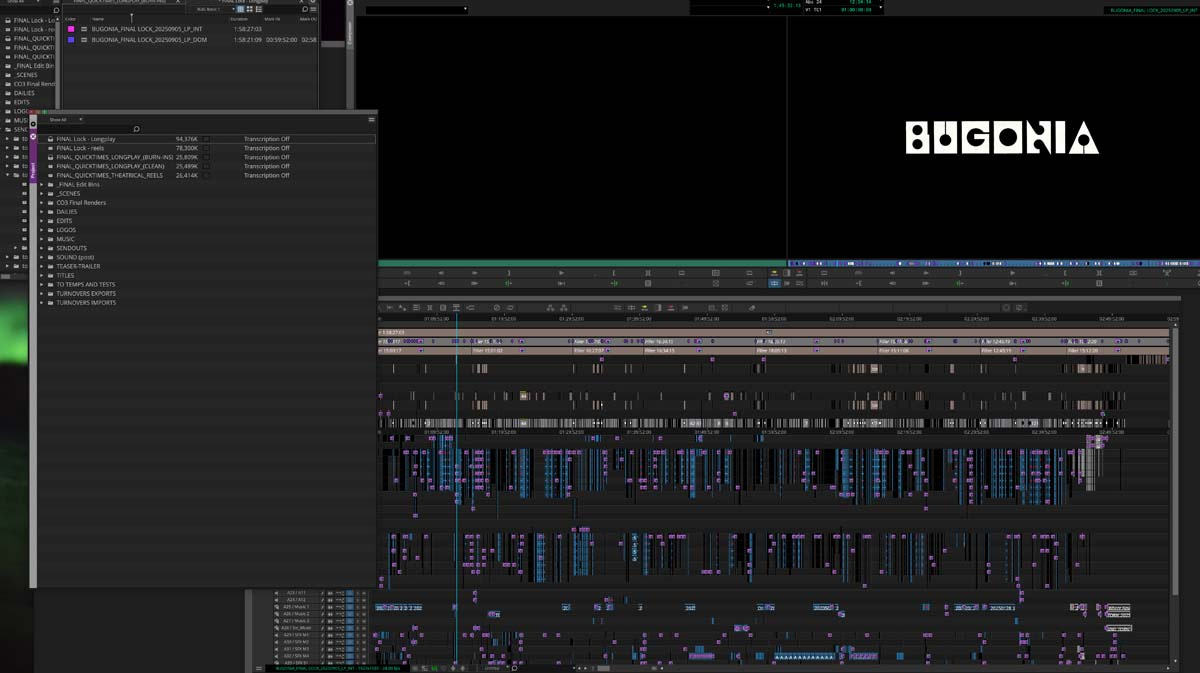

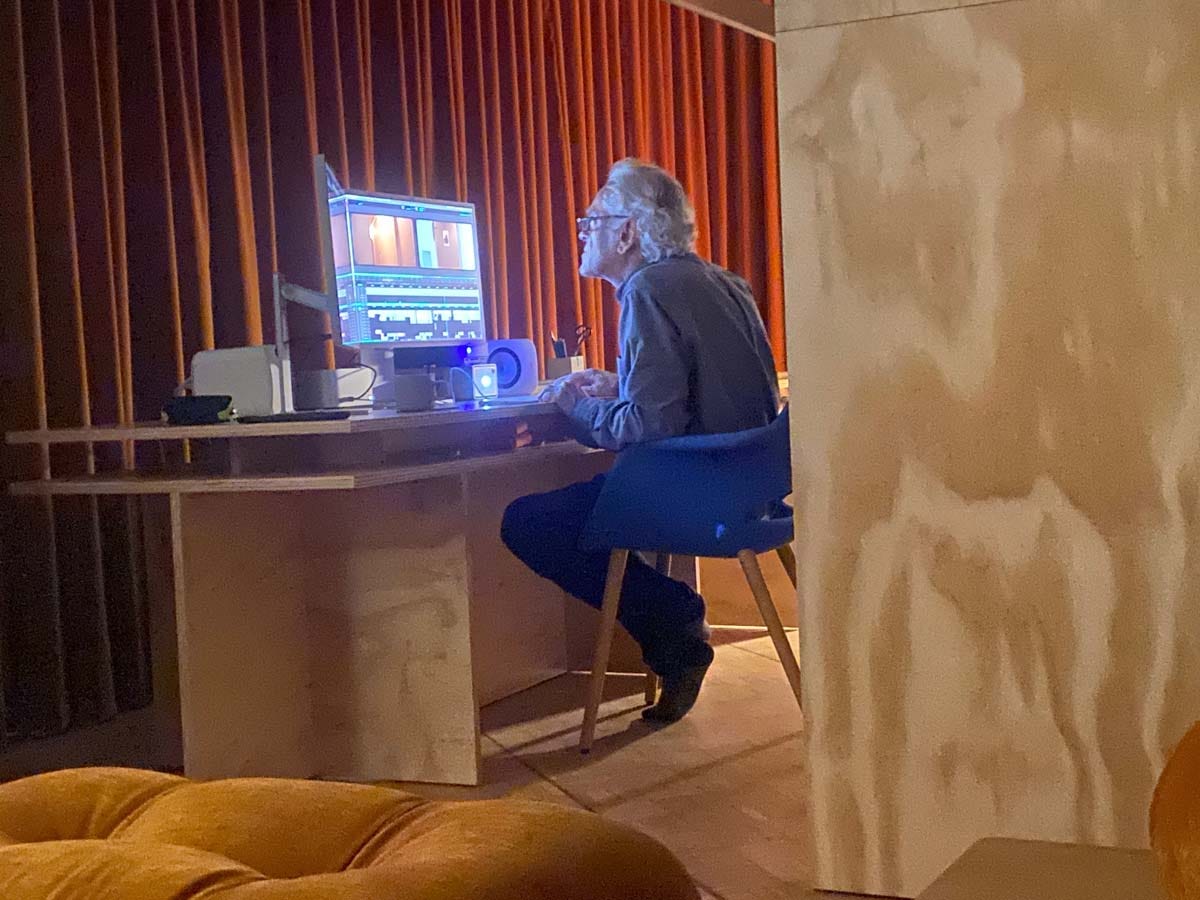

Not Lanthimos. The other one. Yorgos Mavropsaridis. Lanthimos’ editor of 20 years.

In a recent conversation with Steve Hullfish on the Art of the Cut podcast, Mavropsaridis walked through his editing process on Bugonia and we’re taking a deeper look.

The Two Yorgos: A Love Story

Mavropsaridis has edited every major Lanthimos film since Kinetta in 2005. That’s Dogtooth, The Lobster, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, The Favourite, Poor Things, Kinds of Kindness and most recently Bugonia. Twenty years of the same director-editor team, developing what cinematographer Robbie Ryan calls a “creative shorthand.”

In a normal production, the editor can sometimes be viewed as the fixer. The person who comes in after filming wraps and salvages the mess.

Mavropsaridis rejects all of that. His editing is deeply philosophical, drawing on Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze (light reading for your average film editor) to foreground what he calls the “essential aspects” of cinema: that it unfolds in time and is made of ever-differentiating planes of movement.

Which is a very fancy way of saying: he makes you sit with your discomfort.

Mavropsaridis and Lanthimos met in the least cinematic way possible: editing commercials in Athens in the early 2000s.

Mavropsaridis was already established: 20 years older and comfortable in the commercial world. Lanthimos was just starting out, directing music videos like these:

They’re nothing like the deadpan, fish-eye absurdism he’d become famous for. Which is the point. Young Lanthimos was experimenting, and figuring out what his voice even was.

And Mavropsaridis was about to spend the next two decades helping him find it.

Greek Weird Wave

In the early and mid-2000s, as Greece’s economic crisis deepened, a generation of filmmakers started making deeply strange, politically allegorical films characterized by deadpan delivery, static framing, absurdist violence, and an overall vibe of “everything is wrong but we’re going to speak about it very calmly.”

Think Dogtooth, Attenberg, Alps.

Lanthimos became the international face of the movement, but he wasn’t working in isolation. Director Athina Rachel Tsangari produced his early work and made Attenberg (2010), which is just as essential to understanding the movement.

These filmmakers were all in Athens, collaborating on each other’s projects, developing a shared aesthetic of clinical detachment and social critique.

The Yorgos Weird Wave

Dogtooth (2009) - A couple keeps their three adult children imprisoned in their family compound, teaching them a fabricated language and reality

The Lobster (2015) - In a dystopian future, single people have 45 days to find a romantic partner or be transformed into an animal

The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017) - A surgeon’s life spirals into nightmare when a teenage boy he’s befriended begins exacting a bizarre form of revenge

The Favourite (2018) - Two cousins compete for Queen Anne’s affections in 18th century England - this was their most “conventional” film to date which says a lot because it’s still pretty weird.

Poor Things (2023) - A woman brought back to life by a scientist embarks on an adventure across continents, free from the prejudices of her time.

Each film refined the technique and pushed the boundaries of how long you could hold a shot or how uncomfortable you could make an audience without losing them entirely.

And then came Bugonia. Which strips everything back to its essence.

Ambience and ambiguity

For Bugonia, Lanthimos made a decision that would fundamentally shape how Mavropsaridis could edit the film: shoot on VistaVision.

The legendary 1950s format that creates images of extraordinary resolution. It’s the format of Vertigo and The Searchers. It’s gorgeous and gorgeously impractical.

They used a Wilcam W11, a “one-of-a-kind” high-speed VistaVision camera that operator Colin Anderson described as sounding “like a coffee grinder.” A camera that loud destroys the possibility of recording clean dialogue on location.

Which means: ADR.

On most films, making ADR sound natural is a problem. When dialogue is recorded in a studio and laid over the image, it lacks the chaotic resonance of a live environment. But Lanthimos and Mavropsaridis embrace artificiality.

Voices float slightly above the image. And in a film about a conspiracy theorist who may or may not be completely delusional, that separation between voice and body elevates the ambiguity even further.

The Wilcam W11 takes five minutes to reload and in the high-pressure environment of a film set, that’s an eternity. Even blank check directors like Lanthimos can’t shoot endless takes.

For Mavropsaridis, this meant fewer setups to work with. He had to rely on long takes, letting scenes play out in the wides. Which of course, is a Lanthimos staple.

Breaking Bugonia

Mavropsaridis drew upon film theory, specifically the work of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, whose two-volume Cinema books are basically the editor’s bible if you’re into making audiences suffer (artistically).

Quick film theory crash course:

Deleuze distinguished between two types of cinema, and understanding the difference is key to understanding what Mavropsaridis does.

The Movement-Image (classic Hollywood): You see a threat → you feel fear → you run or fight. Time is just measuring how long the action takes.

The Time-Image (art cinema): You see something incomprehensible → you can’t react → you’re just... stuck there, witnessing.

Bugonia employed Time-Image.

The plot is essentially a waiting game. Teddy and his autistic cousin Don hold Michelle captive, waiting for a lunar eclipse to prove she’s an alien. Most of the film is just... waiting. Watching them eat. Watching them sleep. We’re not experiencing “how long until the eclipse?” We’re experiencing time as a pure force that crushes the characters.

Many reviewers noted that the editing feels like it cuts “just a second too late or too soon.” This is all intentional.

Cutting too late: The dialogue finishes. Conventional editors cut immediately. Mavropsaridis lets the silence hang. Forces you to sit in the “dead time” after speech. It transforms the scene from narrative exchange into uncomfortable intimacy.

Cutting too soon: He might cut away before a reaction is fully processed, denying you the emotional release of seeing a character respond. Unresolved tension builds and you’re completely denied catharsis.

Cutting room floor

In a typical film, we get the backstory or the trauma dump. Or the flashbacks.

If Bugonia was a typical film, we’d see Teddy’s childhood. The pharmaceutical company actually destroying his family at length. His bees dying. Something to rationalize why he’s holding a woman captive in his basement.

Mavropsaridis cut all of it.

No flashbacks. No explanatory montages. Just the suffocating present of the kidnapping.

Well, there is a flashback but it’s incredibly opaque and not a tearful cutaway to his past.

Mavropsaridis leans into nuance. In Plemons’ performance, the tension of his jaw, manic certainty in his eyes and the way he handles his bees are all front and centre. Right now.

This also only works because Plemons is an exceptional actor. His entire character history has to be legible in his performance alone.

The Bugonia Trailer Is an All-Timer

A bit of a sidenote as Mavropsaridis didn’t edit the trailer. That was Alyssa B. Aldaz at New York’s Giaronomo, but it’s arguably just as masterful an edit as the film itself.

Giaronomo has cut trailers for Asteroid City and The Phoenician Scheme, and they clearly studied Mavropsaridis’s playbook and transferred it to trailer form.

The Chappell Roan needle drop shouldn’t work but absolutely does.

“Good Luck, Babe!” was everywhere in 2025 as a queer anthem. TikTok, pride parades, your friend’s Instagram story captioned “me at my ex’s wedding.”

And there’s Emma Stone, high-powered CEO in her G-Wagon drinking her smoothie on her morning commute, absolutely belting it out like she’s driving to a breakup and not a board meeting.

Taking a song about heartbreak and using it to soundtrack a woman who’s about to be kidnapped by a conspiracy theorist who thinks she’s an alien from Andromeda is gloriously absurd. Camp in the best way.

The trailer even restarts halfway through. Literally glitches and begins again, mirroring the scene where Stone’s CEO character flubs her corporate diversity puff piece speech and has to start over.

Best trailer I’ve seen in a long, long time.

And it worked. The film pulled in $40 million at the box office on a $40 million budget, less than the $118m haul for Poor Things but more than Kinds of Kindness’ $15m.

A $40M draw for a kooky Lanthimos film about bee conspiracy theories is honestly impressive.

Now it’s positioned as a major contender heading into the Oscars in March, with expected nominations for Stone, Plemons, and hopefully, finally, for Mavropsaridis in editing.