Could AI save Springfield?

Four decades in, The Simpsons is confronting its most human problem and its most digital solution.

Hi everyone —

The week is going great. We released a lot of updates, fixes, and improvements to Eddie AI. Small stuff, in isolation. But altogether, meaningful.

Hope you see Eddie continuing to get better for your video editing needs.

Enjoy today’s newsletter. Comment to leave any thoughts or hit reply.

Best,

Shamir

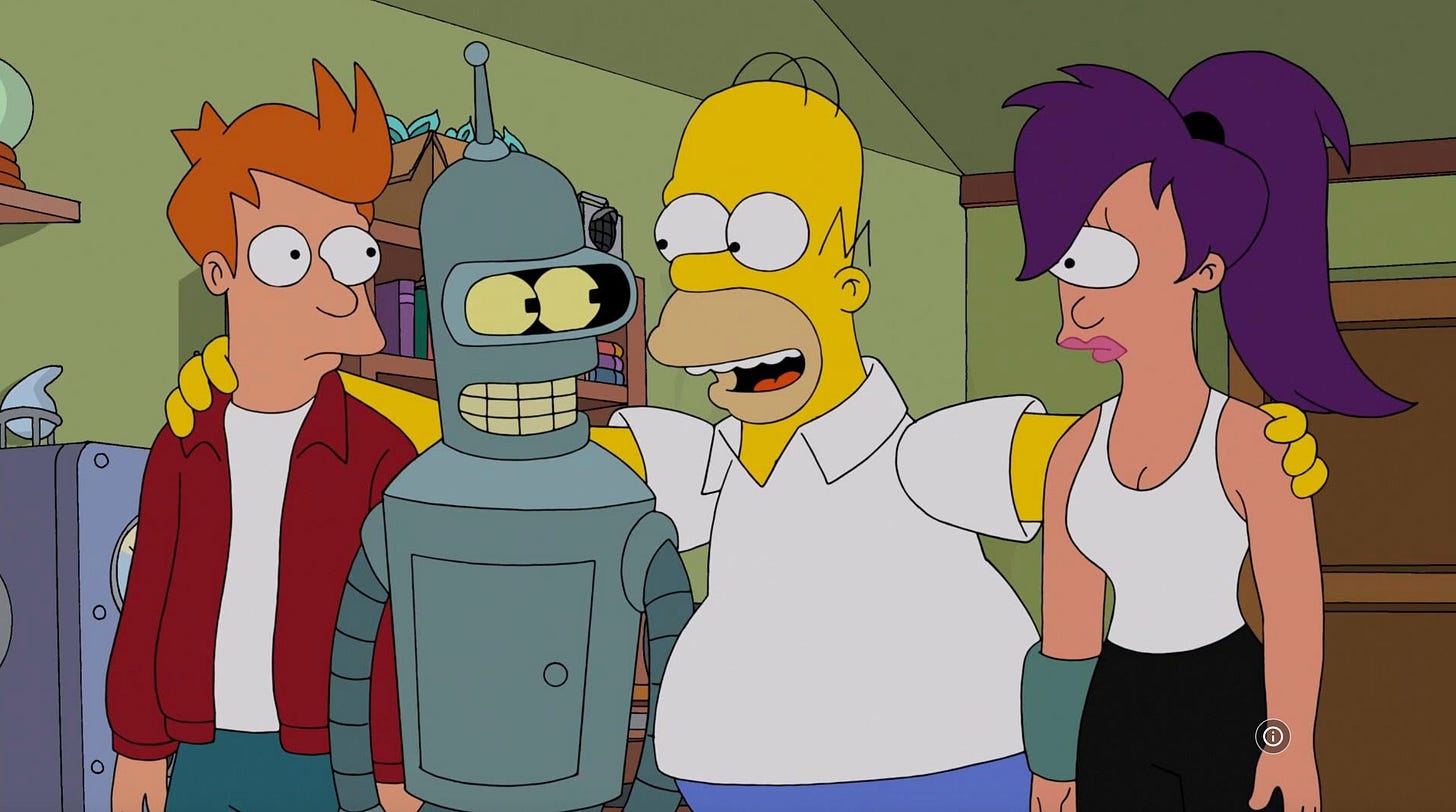

The Simpsons Movie 2 is officially happening.

The 2007 movie was a hit, but even back then critics said it had arrived a decade too late.

Now, imagine that 20 years on from that we have another Simpsons film on the horizon. It’s a gap so wide the upcoming film feels more like a seánce than sequel.

It’s a film that must contend with the show’s golden age far behind it, its audience fractured, and its cast… audibly aging.

It’s wild to realize that the gap between The Simpsons’ first episode and its 2007 movie is now almost the same as the gap between that movie and its upcoming sequel.

While the sequel will likely be the first time many people have watched The Simpsons since 2007, some critics have voiced concern. As one commenter put it, “Audiences are going to be shocked when they hear how Marge actually sounds now.”

That raises a fascinating and uncomfortable question:

How much longer can The Simpsons cast actually keep doing this?

The show may be twenty years past its sell-by date (if not longer) and sadly, its actors are nearing theirs.

Springfield might be frozen in time, but its cast are truly running out of it. But what if there’s a solution?

Ending it?

Yeah, that’s not happening any time soon.

Earlier this year, Fox renewed The Simpsons for another four seasons, ensuring its run stretches well past 2030.

The other potential solution is the elephant in every Hollywood room right now: AI.

For months, the industry has been mourning what many call the death of human creativity: from voice cloning to digital doubles to synthetic actors.

But for The Simpsons, it’s the same tech that might be the only thing keeping it alive.

The Sound of Time

By 2027, The Simpsons cast will have been voicing these characters for nearly forty years. An almost impossible stretch in television history.

In its early 90s heyday, The Simpsons was the cultural monolith.

Regularly pulling in over 20 million viewers per episode, with the Season 2 premiere “Bart Gets an F” topping 33 million.

By contrast, new episodes draw just 2–4 million live viewers on Fox, ranking around #100 in overall broadcast ratings. TV audiences have fragmented across streaming platforms so its unsurprising but the scale of decline still shocks anyone who remembers when the show defined Thursday nights.

Yet even as its broadcast numbers fade, The Simpsons remains one of Disney+’s most-watched series and continues to dominate global demand metrics for animated content.

Still, for viewers old enough to have watched it live in its prime, it’s jarring to realize the cast who once sounded timeless are now in their seventies and eighties.

Dan Castellaneta (Homer Simpson) — 32 in 1989 → 70 in 2027

Julie Kavner (Marge Simpson) — 39 in 1989 → 77 in 2027

Nancy Cartwright (Bart Simpson) — 32 in 1989 → 70 in 2027

Yeardley Smith (Lisa Simpson) — 25 in 1989 → 63 in 2027

Harry Shearer (Mr. Burns, Ned Flanders, Principal Skinner, etc.) — 45 in 1989 → 83 in 2027

Hank Azaria (Moe, Apu, Chief Wiggum, Comic Book Guy, and more) — 25 in 1989 → 63 in 2027

“Simpsons Did It” .. but Can They Still Do It?

The longstanding careers of the cast is a testament to durable talent, but also a case study in the limits of human physiology.

As the body ages, so does the larynx. The vocal folds (or cords), composed of muscle and other tissues also undergo significant changes.

The thyroarytenoid muscle: the one that gives the vocal folds their strength, slowly atrophies and loses mass like any other muscle. The lamina propria, the soft, vibrating layer that makes sound possible also grows thinner. Even the mucous membranes that keep everything moving start to dry out.

The result is what doctors call presbyphonia, and fans simply call “What the hell happened to Marge’s voice?” The classic “honeyed gravel” of Julie Kavner’s performance has grown raspier over the years which is a direct byproduct of aging vocal cords.

Adding to the natural wear of time is the sheer physical strain of the job.

Voice actors are, in a very real sense, vocal athletes and the cast of The Simpsons has been running the same marathon for nearly four decades.

These aren’t natural voices (other than perhaps Yeardley Smith’s Lisa Simpson); they’re performances pushed to the edge of what the human larynx can do. Julie Kavner has admitted that Marge’s gravelly tone “hurts to do,” and yet she’s been doing it since 1989.

After 35 years of “D’ohs,” screams, and strained falsettos, it’s no wonder the cast’s instruments are showing fatigue. And unlike most athletes, they can’t really be replaced without replacing the entire show altogether.

Machines in the Yellow Ghost

The use of AI to “de-age” or even fully recreate voices is no longer science fiction.

It’s been deployed in some of Hollywood’s biggest franchises offering a potential, if contentious, roadmap for The Simpsons.

The tech, developed by companies like Respeecher and Sonantic, uses deep learning algorithms to create a vocal model.

The process would involve training an AI on hours of dialogue from the show’s prime, allowing it to learn the precise pitch, timbre, and cadence of each character in their heyday.

Given the fact The Simpsons has been on air since the first Bush administration, the AI won’t exactly be short on data.

The original actors would still deliver the new lines but the AI would then “convert” this new recording, mapping the actor’s performance onto the younger-sounding vocal model.

The precedent is already here.

In The Mandalorian, Disney used voice-cloning tech from Respeecher to recreate a young Luke Skywalker even though Mark Hamill never recorded a single word.

The AI rebuilt his 1980s voice from archival dialogue, matching tone so precisely that most viewers never noticed the illusion.

The same technology helped late Val Kilmer speak again in Top Gun: Maverick, restoring the sound of his pre-illness voice after throat cancer left him unable to perform.

And it’s not limited to blockbusters. Respeecher was used in Bradley Corbet’s The Brutalist to perfect Adrien Brody’s Hungarian pronunciation, and in Jacques Audiard’s Emilia Pérez to refine the film’s musical performances.

It’s a reminder that AI voice synthesis isn’t just a gimmick or nostalgia trick, but a creative instrument already shaping both Hollywood spectacle and art-house cinema alike.

The Simpson's Factory

One of the clearest precedents comes from Netflix’s 2022 docuseries The Andy Warhol Diaries. To have Warhol “narrate” his own story, director Andrew Rossi used AI to recreate his voice.

The method was a hybrid: actor Bill Irwin recorded the diary entries, and an algorithm trained on the limited archival audio of Warhol himself transformed them into the artist’s unmistakable monotone.

Rossi secured permission from the Andy Warhol Foundation and argued that Warhol, who once declared in 1963 “I want to be a machine,” would have loved the idea.

The result was eerie, poetic and a glimpse of how technology can blur the line between resurrection and recreation.

From the Neck Up

For Hank Azaria, the fear of AI is just as much about losing work as it is about losing the performance.

In an essay he wrote for The New York Times in February this year:

A misconception about voice acting, is that it takes only a voice. But our bodies and souls are involved to get the proper believability.

When Azaria first joined The Simpsons in his early twenties, he remembers watching Dan Castellaneta and Harry Shearer in the booth.

They were jumping around, throwing punches, crying real tears. I was embarrassed at first. It took me a while to get up the courage to do that too.

To Hank, to sound like someone running, you run.

Azaria once even stuck a highlighter in his mouth to simulate a cigar for a gruff character. The result is a performance that comes from muscle memory as much as from imagination.

That, he says, is the part AI can’t reach. At least, not yet.

It’s the neck-up version that I can see A.I. being capable of. The body and soul part will be harder.

Still, Azaria isn’t completely dismissive.

I miss dearly Mel Blanc’s old Bugs Bunny performances. We’ll never get them again. But maybe with A.I., we can have more of them.

And it’s that exact tension between loss and resurrection, between mortality and memory that makes AI such an uncanny prospect for The Simpsons.

742 Forevergreen Terrace

AI could potentially preserve not just the show’s sound but its entire legacy. Yet the very idea carries enormous ethical concerns.

The biggest is consent.

The actors’ voices are both their livelihood and their identity, and digitally cloning them would require intricate negotiations around ownership and creative control.

It also begs further questioning: Once the actors are gone, who owns the sound of Springfield?

Who gets paid when the show keeps talking but the people behind it no longer can?

That question lives in a legal gray zone.

Under current SAG-AFTRA rules, royalties flow to an actor’s estate as long as their original performances are reused. But if a studio creates new performances using AI-trained replicas of those voices, the line blurs.

Unless contracts explicitly extend rights to digital likenesses, the estate may have no claim to those earnings.

In that scenario, Springfield could keep talking and the families of the people who gave it a voice might never see a cent.

But perhaps the deeper question is spiritual.

The Simpsons has always been about the gap between who we want to be and who we actually are. Homer chasing donuts he’ll never stop craving. Marge holding a family together that keeps falling apart. A town frozen in perpetual imperfection.

Now the show itself faces that same gap: between the Springfield we remember and the one that’s still being made, between the voices that defined our childhoods and the vocal cords that can no longer sustain them.

Maybe AI offers a way to close that gap. Or maybe it just lets us pretend it was never there.

Either way, The Simpsons Movie 2 will arrive in 2027 and for the first time in the show’s history, the voices of Springfield might be neither fully alive nor fully synthetic but instead something unsettlingly in between.

If you enjoyed reading this article please like and share!