Ed Pincus, the Documentarian Who Turned the Camera on Himself

Plus a new initiative to support documentary filmmakers

Hi friends,

This week’s edition of The Rough Cut is a special one, not just because of the story we’re telling (we’re talking all about documentarian Ed Pincus), but because of what we’re launching alongside it.

Today, I’m proud to introduce 1,000 Docs—an initiative to support documentary filmmakers by giving away 1,000 subscriptions to Eddie AI Pro (if you’re doing the math, that’s over $1M in product value…)

When we started building Eddie, it wasn’t just about saving time. It was about giving storytellers more room to focus on what matters: the story itself. And one group of storytellers in particular, doc filmmakers, have been using Eddie to assist them so they can focus on their big documentary stories.

Docs don’t just entertain us. They expose what’s broken, lift up what’s overlooked, and remind us what it means to pay attention. We love docs. And more than that, they are really important to robust societies that believe in dialogue and debate.

If you’re a doc filmmaker working on your dream indie doc, we’d be honored to support you. Here’s how to apply:

Applications are open now through July 31

If accepted, you’ll get access to Eddie Pro + onboarding support from our team

Have questions? Just hit reply and I will answer them!

Please share this with your filmmaker friends and communities.

Now onto this week’s essay. It felt right that this week’s Rough Cut explores one of the most quietly radical documentarians of the 20th century: Ed Pincus. Long before confessional vlogs, parasocial TikToks, or influencer overshares, there was Diaries (1971–1976) a radical act of self-surveillance and vulnerability.

Let’s rewind.

—Shamir

The Philosopher with a 16mm shooter

Born in Brooklyn in 1938, Ed Pincus was Ivy League material from an early age. He studied philosophy at Harvard and could’ve spent his life behind a lectern quoting Nietzsche but the world outside was burning.

Civil rights marches, assassinations, Vietnam. The 70s was trying time and Ed didn’t want to theorize about the turmoil.

He wanted to be in it.

So he did what no tenured academic would recommend: he got a Bolex and hit the trenches.

In 1966, with no formal film training Pincus packed his car and drove down to Natchez, Mississippi, a town crackling with racial tension. Ku Klux Klan still looming large.

And in the middle of it, Ed started rolling.

The result was Black Natchez, one of the earliest examples of white documentarians embedded within the Black freedom movement, though even that phrase feels wrong.

Ed didn’t “embed.” He didn’t interview from a distance. He got close. Too close.

He captured men debating protest strategy in church basements. Mothers warning their sons to stay off streets.

No narrator. No cutaways. No safety net. Just Ed and his camera.

He was only 28 by the way.

And already violating the golden rule of documentaries: don’t become part of the story.

MIT, A Backpack, and a Blueprint

Ed went back to MIT and there, alongside David Neuman, he helped write Guide to Filmmaking, an instructional bible for indie filmmakers in the 1970s. This wasn’t some glossy coffee-table book or how-to for gearheads. It was radical. Ground-level. Anti-Hollywood.

He believed the camera always changed things, always. So rather than pretend otherwise, he leaned in.

The filmmaker wasn’t just part of the story, the filmmaker IS the story.

What we experience is only through the eyes of the filmmaker meaning it is their story as much as it is the subject.

Ethically and morally that posed a few uncomfortable questions but he wasn’t interested in pretending to be invisible.

He was interested in truth. And sometimes that meant becoming the story.

And it was this methodology that would all come to a head in the film that nearly cost him everything.

The Cut That Nearly Cost Him Everything

Between 1971 and 1976, Pincus did the unthinkable: he turned the camera on his own life.

No subject to find. No source. No research. All there in plain sight. In his own home.

Diaries wasn’t a doc in any conventional sense.

A raw, unflinching portrait of his marriage, children, friends, and even affairs. Arguments. Intimacies. Even confessions about sleeping with students.

The slow, painful erosion of a relationship, captured in real time.No talking heads and no voiceovers. Just real life unfolding on film in all its chaotic glory.

Audiences didn’t know how to process it. Was it art? Narcissism? Masochism? Death wish?

Pincus weaponized the camera against himself. And in doing so, made something terrifyingly honest.

Perhaps too honest..

A Reel Too Real

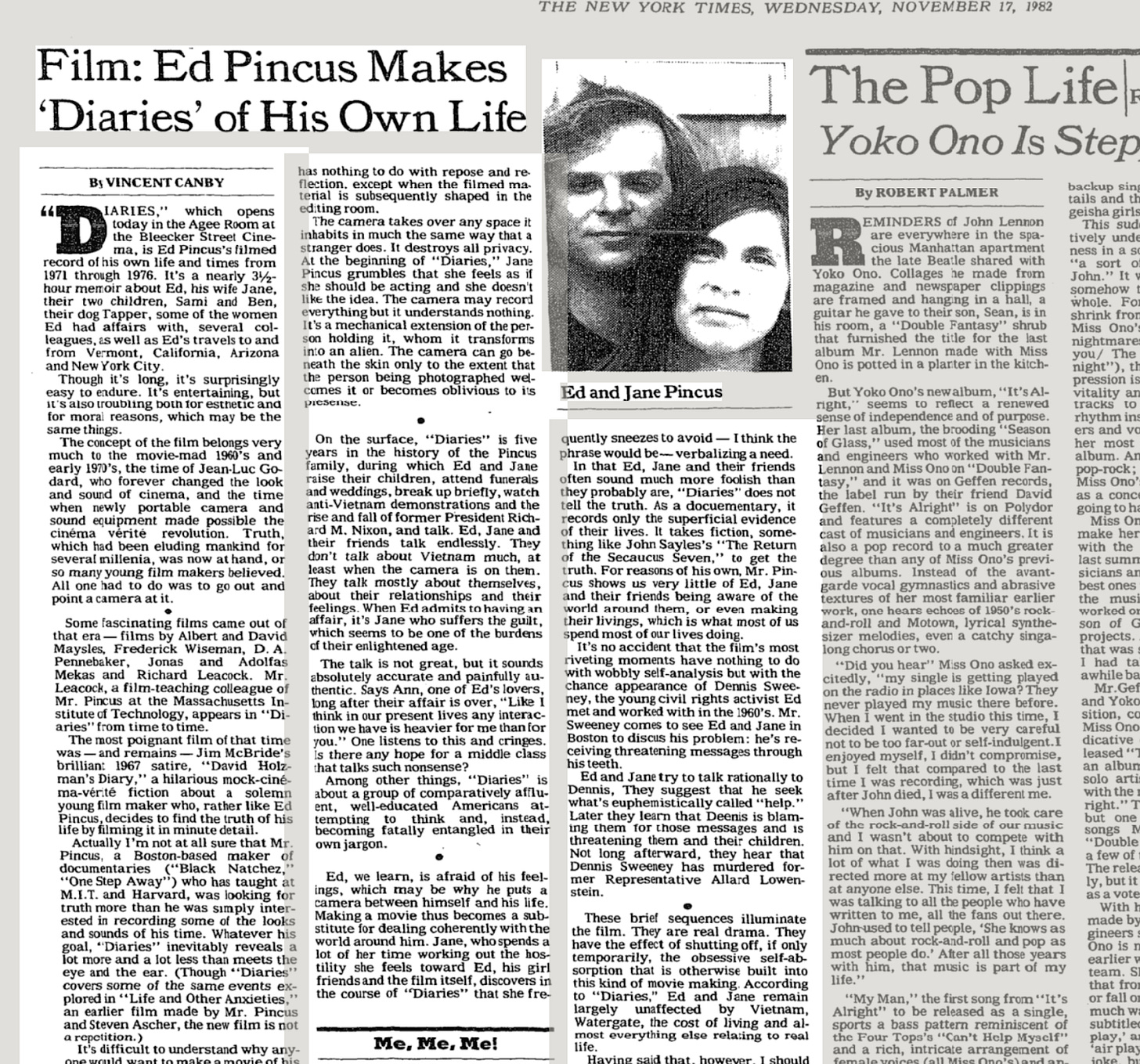

1982 review of Diaries

In the wake of Watergate, Americans were hungry for transparency.

Just maybe not this much.

Critics called Ed a voyeur. Narcissist. Exploiter. The 1982 New York Times review in particular, didn’t pull any punches:

“It's entertaining, but it's also troubling—both for aesthetic and moral reasons, which may be the same thing.”

“It's difficult to understand why anyone would want to make a movie of his own life, unless one were a filmmaker in search of a subject. It's not the same thing as writing about one's life.”

“The camera takes over any space it inhabits in much the same way that a stranger does. It destroys all privacy.”

At the start of Diaries, his wife Jane Pincus tells him, “I feel like I should be acting. I don’t like it.”

Neither, it seemed, did the film world.

So Ed did something even more radical than baring his life on camera; he disappeared from the frame entirely.

The 20-Year Sabbatical

Ed vanished. Not into scandal or obscurity but into soil.

He moved to rural Vermont with his wife Jane and became something few filmmakers with notoriety ever imagine becoming: a flower farmer.

Zinnias, garlic, and peonies. Rows of them. He traded film reels for root stock, swapped 16mm for pruning shears. His peonies made the local rounds like they were Sundance darlings. One grower called them “so good they caused a stir.”

He called it Third Branch Flower Farm. And for over 20 years, that’s where he stayed.

He kept his camera close but rarely fired, focusing instead on a quiet photo series of rural Vermonters. Intimate. Still. Never public.

And in the film world, he became a rumor. A pioneer who made one radical cut, then never came back.

Until he did.

The Storm That Pulled Him Back

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit. Entire neighborhoods swallowed and many lives scattered.

Something in Ed Pincus cracked open.

After two decades in exile, he picked up the camera again. But not to look inward this time. To look out.

He teamed up with filmmaker Lucia Small, and together they hit the road. Not with a production schedule. With questions. Their film The Axe in the Attic wasn’t about the hurricane itself. It was about the aftershocks. The grief. The gaps.

The America left behind.

Shot from inside cars, diners, motels, FEMA trailers, it’s a film that drifts, searching for meaning amongst the wreckage.

The camera, long dormant, was back in his hands. But the gaze was different now. Less omniscient. More vulnerable. Less “here’s what’s happening.” More “should we even be filming this?”

That question haunts the film as do many others.

Are we helping? Are we spectators? Are we just tourists of trauma?

You’ll have to watch it to see how those questions get answered, if at all.

A Final Frame

In 2011, Ed Pincus was diagnosed with leukemia.

His final film, One Cut, One Life (2014), co-directed with Lucia Small, became a quiet reckoning on death, memory, and what we leave behind.

He sadly didn’t live to see its release.

And yet, his fingerprints are everywhere.

It's hard to draw a straight line from his film Diaries to TikTok therapy dumps or vloggers crying into handheld cameras but the template was there.

He filmed himself long before it was normal. Or safe. Or monetizable.

He made cinema personal. And in doing so, made it universal.

Extra’s

A few of the substacks we’ve been loving