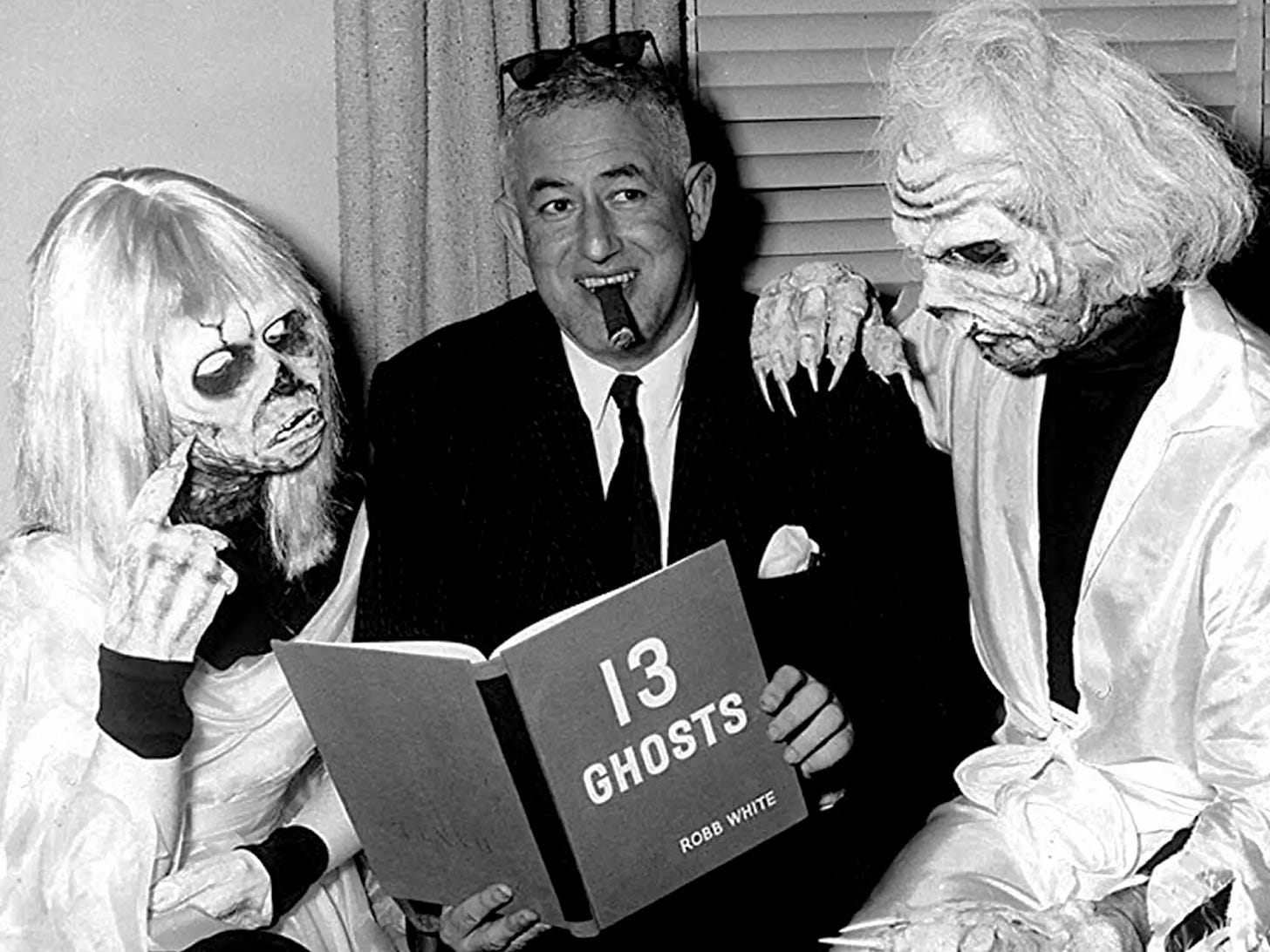

Hidden Hand: William Castle, the horror gimmick king who offered audiences a $1,000 life‑insurance policy in case they died of fright

⚠️ Reader Advisory: The following newsletter will self-destruct in 10 minutes

Hey friends,

Big one this week: Scripted Mode just dropped.

If you work with interviews, explainers, or short-form scripted content, this one’s for you. Upload your footage + script, and Eddie builds a rough cut in minutes — picking the best takes and lining everything up like magic.

No more digging for soundbites. No more manual syncing. Just a clean stringout, ready to go.

It’s already changing the game for YouTubers and creative teams. And we’re just getting started. Now, from editing efficiency to the king of chaos…

This week’s Rough Cut is about William Castle, the B-movie legend who turned fear into a business model. From fake insurance policies to skeletons flying over theater seats, Castle didn’t just promote his films — he engineered experiences. Before anyone was talking about “audience engagement,” he was out there making moviegoing feel like a live event.

It’s a wild story, part history lesson, part marketing blueprint, and a good reminder that sometimes the most outrageous idea is the one that sticks.

Let’s dive in.

— Shamir

In 1958, William Castle, Hollywood’s reigning prince of B-movie chaos was one flop away from irrelevance.

TV was killing theaters. Horror was recycling the same latex ghouls. And Castle was forced to mortgage his Beverly Hills house so he could make a 72-minute horror flick called Macabre.

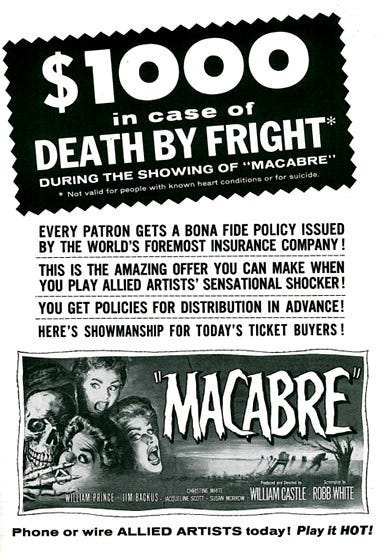

Every ticket came with a $1,000 Lloyd’s of London life insurance policy. Payable if you literally died of fright.

The fine print was longer than the script, but if you read it you’d find out that the policy was void if you had “pre-exisiting” conditions.

Castle became the king of the gimmick. What followed that was flying skeletons, vibrating seats, from a man who basically invented experiential marketing before “immersive” became a thing..

Hollywood, forever thirsty for attention, took notes.

And you should too.

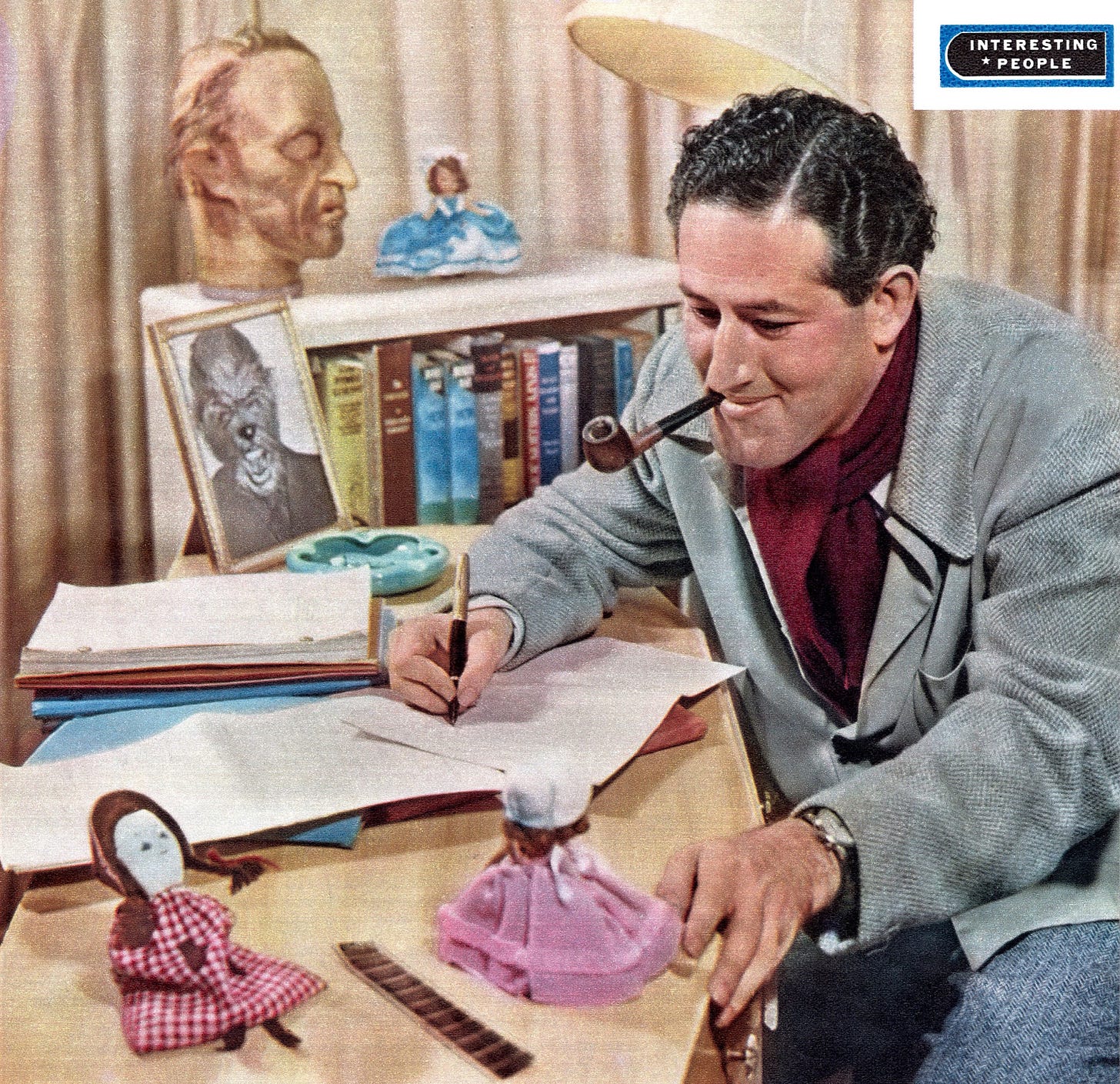

Who was William Castle, really?

Well, the real William Castle wasn’t even William Castle.

He was born William Schloss Jr. in New York City, 1914. Orphaned at age 11, he was hellbent on cracking Hollywood at an early age and ditched “Schloss” (German for castle) in favor of literally William Castle as his stage name.

At 15, he dropped out of high school to chase a touring Dracula gig. Spending his teens on Broadway doing everything: sets, lights, acting, eavesdropping.

Yearning to direct his own play, Castle somehow talked his way into leasing Orson Welles’ theater, hired a German actress, but ran into union rules that said she could only perform in plays staged in Germany.

So naturally, he made one up.

“Das ist nicht für Kinder”, he called it and wrote it over a weekend.

When the Nazis invited her to perform in Munich, Castle forged a telegram saying she refused, calling her “the girl who said no to Hitler,”.

Castle then painted swastikas on his own theater to sell more tickets.

At 23, Castle packed up and headed to Hollywood, landing a job at Columbia Pictures as a dialogue director then got bumped to studio B-movie director alongside names like Fred Sears and Mel Ferrer.

Now, he was getting his first taste of the movie business.

Macabre (1958): The Film That Came With a Life Insurance Policy

Coming from the studio system, Macabre was Castle’s first fully indie film.

Plot-wise, Macabre was pure B-movie pulp:

“A small-town doctor’s infant daughter is kidnapped and buried alive… with only a few hours of oxygen left. He’s forced to race against time, navigating blackmail, murder, and small-town paranoia to find her before she suffocates.”

Exactly the kind of cheap, lurid thrill Castle knew how to sell.

But the real drama was off-screen.

Castle couldn’t get studio backing, so he mortgaged his Beverly Hills house for $90,000 ($1M in today’s money) and financed it himself.

Then, to make sure people actually showed up, he cooked up the now-infamous $1,000 life insurance gimmick.

Betting not just his money, but his reputation, on the idea that fear could sell if you made it loud enough.

It did. The movie made $5 million against a $120K budget.

Every screening began with a black screen and a ticking countdown clock.

Castle’s voice came over the speakers to calmly inform you that yes, your ticket included a real $1,000 life insurance policy.

And no, they’re not covering you if you have a pre-existing heart condition.

In the unlikely event you did in fact die of fright during the film, your heirs would be compensated.

Audiences showed up in droves, some curious, some skeptical, all ready to be part of whatever the hell this was.

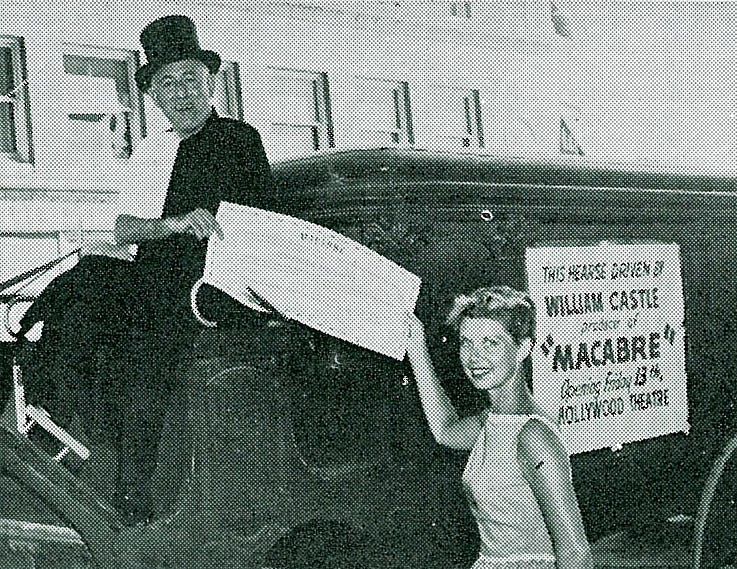

What watching Macabre in the theater would have looked like

Hearses parked outside like a mobile morgue.

Nurses patrolling aisles with stethoscopes and smelling salts.

Castle popping out of a satin‑lined coffin for the curtain speech.

The Gimmick Arms Race

By the early ’60s, the horror game was getting crowded.

Studios were cranking out creature features like fast food, and TV was poaching Castle’s audience one rerun at a time.

Worse, theaters were starting to flirt with their own flavor of stunt marketing: motion seats, interactive lighting, even something called Smell-O-Vision, which piped 30 scents into the auditorium whether you wanted them or not.

So Castle doubled down.

Every new film had to outdo the last, turning the theater itself into a booby-trapped haunted house.

Skeletons on strings, buzzers in the seats, live audience vote-offs.

If Macabre was the test balloon, this was the rocket launch.

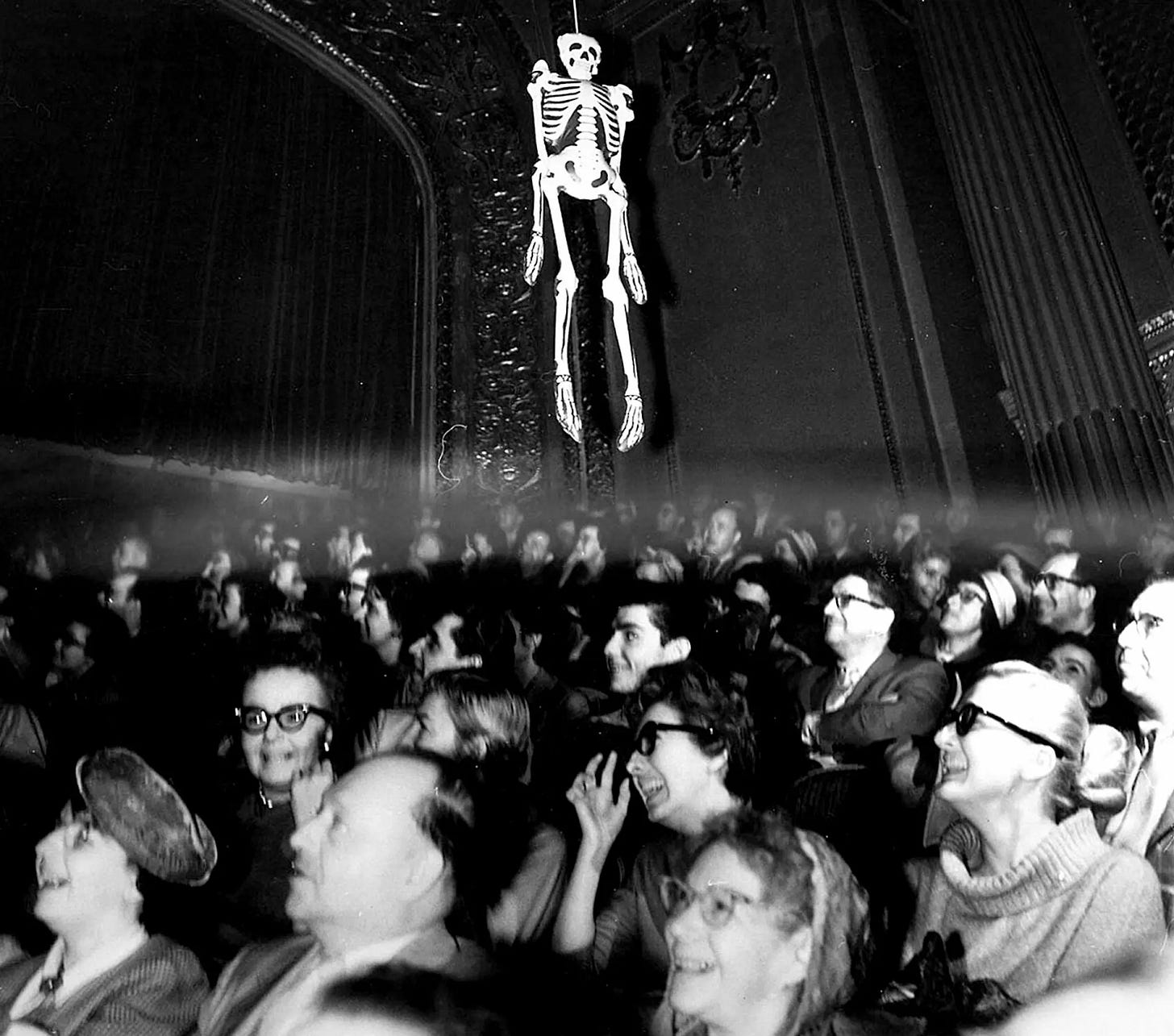

1959 – House on Haunted Hill | Emergo

During the finale, a glow‑eyed plastic skeleton zipped over the audience on a clothesline pulley system.

In some cities pranksters threw popcorn at it, tangling the rig and forcing projectionists to pause the film while stagehands reeled in the plastic bones.

1959 – The Tingler | Percepto

Castle scored surplus Air‑Force de‑icers, mounted them under random seats, and wired them to buzz whenever star actor Vincent Price yelled, “Scream! Scream for your lives!”

1960 – 13 Ghosts | Illusion‑O

Every ticket came with red‑blue ghost viewers. Red revealed the specters, Blue removed them.

Think choose‑your‑own‑haunting decades before interactive cinema was a thing.

Rosemary’s Baby: The Hit Castle Couldn’t Direct

After years of rattling skeletons and buzzing theater seats, William Castle finally caught a whiff of legitimacy.

Rosemary’s Baby, a buzzy horror novel everyone in Hollywood suddenly wanted but Castle got their first.

He mortgaged the house (again), secured rights before anyone else, and for a hot second, he was the most in-demand producer in town.

Paramount loved the project, but not with Castle in the director’s chair.

Shocker.

He’d have to thank one too many gimmicky B-movies for that.

So the studio handed the keys to a 32-year-old first-timer named Roman Polanski. A first-timer that could go on to make Rosemary’s Baby one of the greatest horror films of all time.

If not, the best.

Possibly only The Shining and The Exorcist are its peers.

Despite being the producer, the film’s legacy landed squarely with Polanski. Castle protected it, buffered the studio, stayed out of the way but he’d been around long enough to know when to disappear.

Because his legacy wasn’t directing.

It was showing films how to sell themselves loud, weird, and unapologetically.

Legacy: blueprint for viral hype

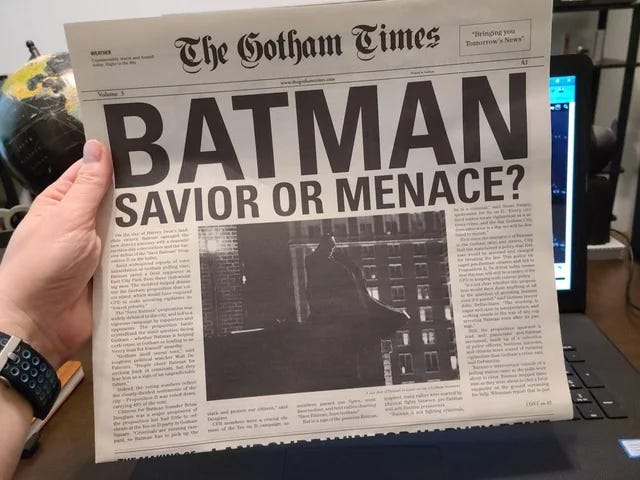

2008 viral marketing for The Dark Knight: fake Gotham newspapers distributed in real cities to blur the line between fiction and reality.

Castle rewired Hollywood’s idea of audience engagement. Before digital teams, before “experiential strategy.”

He was out there winging it, giving moviegoers a reason to dream, scream, and actually show up. And whether they know it or not, today’s marketers are still playing in the funhouse he built.

Here are a few of those modern day marketing strategies that can thank Castle.

Plot into promo Props and tickets becoming part of the narrative. Joker-stamped dollar bills for The Dark Knight ARG and golden tickets for Wonka pop-ups.

FOMO before hashtags One-night-only stunts turn screenings into social currency. The Blair Witch Project used missing-person flyers to blur fiction and reality, fueling word-of-mouth hysteria.

Sensory hacking Some theaters still use 4DX motion chairs, water spritzers, scent emitters, and even temperature shifts to activate senses home setups can’t touch.

Hollywood is constantly searching for ways to get people off their couches and back into theaters.

Premium screens, loyalty perks, bloated runtimes designed to turn movies into all-day affairs (yes, The Brutalist, we see you) nothing sticks like a story you can physically feel.

Maybe what we need isn’t more data. Maybe we need another William Castle.

Someone bold (or unhinged) enough to bet the house (his house), crank up the crazy, and remind us that watching a movie in public should feel like an event.