How a Bronx Kid Infiltrated Lucas Skywalker Ranch (Pt 1)

Before digital rewrote Hollywood, a rock ’n’ roll roadie from the Bronx ended up at the center of the movie business.

Hi everyone —

Before CGI became Hollywood’s default language, Scott Ross was at the center of the revolution. He ran George Lucas’s Industrial Light & Magic (one of my favorite names for a company!!), co-founded Digital Domain with James Cameron and Stan Winston, and helped bring to life The Abyss, Terminator 2, Jurassic Park, and Titanic.

But his story is more than Oscar-winning spectacle. It’s about rebellion and authority, art and commerce, the making—and unmaking—of movie magic.

This is part one of his rise: from Lucas’s secretive dream factory to the renegade, rock ’n’ roll studio he built with Cameron.

Comment. Reply. Message me on X or LinkedIn: let me know what you think of this article.

—Shamir

CEO & Co-founder, Eddie AI

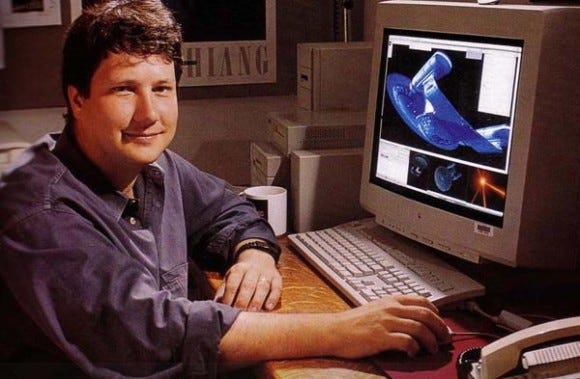

Scott Ross ran Industrial Light & Magic at the dawn of the digital revolution, then co-founded Digital Domain with James Cameron and Stan Winston. Along the way, he helped shepherd films like Terminator 2, The Abyss, Jurassic Park, and Titanic projects that defined modern VFX.

Much of what follows comes from conversations with Scott and readings from his recent memoir Upstart, a front-row account of how he became one of the most revered figures in the post-production world..

This is part one of his unlikely rise.

From the cloistered halls of George Lucas’s ILM to the renegade, Oscar-winning studio he later built with Cameron.

It’s the story of how movie magic gets made and then… unmade.

Rats and Rock ‘n’ Roll

To understand the man who would one day run ILM, we have to go back to the 60’s. New York. The Bronx to be exact. Scott Ross grew up the son of struggling second-generation Jewish parents and two childhood promises helped shape his life.

The first came when his cousins came to see him at his home and blurted:

“YOU’RE SO POOR! HOW DO YOU LIVE LIKE THIS?”

Ross swore he’d never be poor again.

The second came watching his mother emerge from the subway with weary commuters who “looked like insects crawling out of a hole.” They may have looked like insects but it was at that exact moment Scott also swore he’d never join the rat race.

On the “tribal” streets of Queens, music gave him his first stage. Via the blues, then jazz.

During his college years at Hofstra University (Long Island, New York), he worked summers and holidays handling sound for various bands. Then went on to work as a roadie and sound engineer for the Allman Brothers and even toured with Miles Davis.

From the bandstand, he glimpsed the blueprint for the perfect company: singular talents, distinctive voices, creating something greater than the sum of its parts.

That vision of a “rock ’n’ roll company” never left him.

After graduating from Hofstra, rudderless and committed to never getting a “straight job,” he decided to tag along with his college roommate who was headed to the West coast.

He arrived in California with a vague dream of making it as a musician, having packed “about 2,000 records, three pairs of Frye boots, a couple of pairs of Levis, and a toothbrush” for the trip. That dream, however, came to an abrupt and humbling end.

One night at a Stanford coffeehouse talent show, Ross heard someone tackle Charlie Parker’s notoriously difficult Donna Lee. He then turned to see not a seasoned pro, but a boy no older than 14 years old ripping through it with ease.

“That’s when I knew becoming a professional musician wasn’t my future,” Ross recalled. “I’d never be that good and if I couldn’t be at the pinnacle, it wasn’t for me.”

A door closed on a dream that night. But decades later, another door would swing wide open.

The Hippie and the Suit

The next door opened in the parking lot of a company called One Pass. A post-production house based in San Francisco and one of the most important creative hubs on the West Coast during the 80s. .

Ross was sitting in his tricked-out ’72 BMW when a bigger one pulled up beside him.

The driver; skinny, long-haired, moccasins… noticed the car, grinned, and knocked on Ross’s window.

It was Taylor Phelps, president of One Pass.

They clicked instantly over cars and rock ’n’ roll and within minutes Phelps, once a road manager for Crosby and Nash & Young, offered Ross a job on the spot.

Phelps was the embodiment of the “rock ’n’ roll” leader: outrageous, funny, and anything but corporate.

Then came the “suit.”

One Pass was soon acquired by Banta Press, a Wisconsin textbook publisher that sent in Bob Dehlendorf to “whip them into shape.” According to Scott, Dehlendorf was a rough-and-tumble print man who cared little for creativity and everything for the bottom line.

If Taylor Phelps embodied freedom and flair, Dehlendorf was the opposite.

An antagonist, but a necessary one.

Ross didn’t relate to him, but he saw something vital: Dehlendorf had the business discipline Phelps lacked.

Caught between the two, Ross found the defining tension of his career. The people-first ethos of Phelps versus the numbers-driven mandate of Dehlendorf.

His genius would be learning how to fuse them.

Call to the Holy Grail

The call that changed Scott Ross’s life came in the flat tone of a headhunter:

“Lucasfilm’s looking for a new director of operations at Industrial Light & Magic. You interested?”

The role was essentially shorthand for “keep the entire machine running”. As Warren Franklin, Scott’s boss, explained, he would have the managers of “every postproduction and several production departments” reporting directly to him.

That meant oversight of nearly everything that touched the screen: animation, rotoscoping, optical, stage, models, creatures, camera and photography, the screening room, and the nascent computer graphics group.

So when a 34-year-old Ross got the call, the question of whether he was “interested”, really wasn’t a question.

For anyone in the Bay Area film world during the late 70s / early 80s, ILM was the Vatican and George Lucas was its patron saint.

Founded in 1975 to create the impossible shots for Star Wars, the company had since rewritten the rulebook for blockbusters from The Empire Strikes Back to E.T. to Ghostbusters.

George Lucas was already Hollywood royalty.

He had shattered every box office record, won six Oscars and defined what visual effects could do. The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi in particular, had cemented the Star Wars franchise as a cultural juggernaut, while Raiders of the Lost Ark and Temple of Doom extended his reach into yet another blockbuster series with Steven Spielberg.

Getting a call from ILM was the invitation onto Hollywood’s highest table. To make the decision even easier, Ross was also eyeing his exit as president of One Pass.

What he didn’t know was that on the other side of that call was a corporate culture as strange and spectacular as any galaxy far, far away.

The Receptionist Will See You Now

Not one. Not two. Not even fifteen interviews.

Before Scott was hired at ILM, he would have to dance through a grand total of FORTY interviews.

Yes. 40.

40 interviews stretched over months with even the receptionist having a stab at him. What on earth would they possibly need forty interviews for?

Well, Silicon Valley can be absurd. Hollywood even more so but at ILM, Ross found himself caught in the best and worst…of both.

ILM wasn’t like any other 80s startup.

It was a fortress in the Bay and the culture was paranoid. Everyone feared losing their place, so everyone had a voice. “It was sort of like the Hell’s Angels,” Ross said.

The interviews were less about Scott’s résumé and more about sizing him up.

Would he disrupt the fragile balance? Would he support a workforce that already felt squeezed?

For Scott, the circus was worth it. He was trading One Pass for one shot at the Holy Grail.

Welcome to the Dream Factory (Some Assembly Required)

Driving to work that first day, Scott felt like a minor leaguer called up to the Dodgers.

ILM’s headquarters weren’t in some gleaming campus but in a San Rafael strip mall off Kerner Boulevard. The carpets were a funky green and the sign still read Kerner Optical, a cover story to mask what was really happening inside.

Lucas wanted the world to think this was just another strip-mall optics shop. But it was a deliberate cover, a symbol of the fear that Scott saw baked into ILM’s culture.

Everyone inside knew they had the job.

The best gig in the industry. And they guarded it like the illuminati.

Even the carpet carried meaning. Those green-carpeted front offices belonged to management, and the artists mocked their bosses as the “Green Carpet Gang”. More suits who didn’t understand the blood, sweat, and brilliance it took to make movie magic.

In one of his first meetings, Scott even found himself at the table with a young Steven Spielberg, discussing effects for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

But the dream turned disorienting fast.

Scott came from video post-production, a world that was already electronic and edging into digital. At One Pass, he’d worked with cutting-edge systems like the Quantel Paintbox and Harry. Computer-based tools with graphical interfaces that let artists manipulate images directly on screens.

ILM’s world couldn’t have been more different.

Everything ran on film. The raw material was 35mm VistaVision celluloid. Physical strips with sprocket holes. Shots were re-photographed through optical printers, each element combined frame by frame.

To see the result of a single shot, film had to be hand-carried to a San Francisco lab, chemically processed, then returned days later across the Golden Gate. Often only to reveal a mistake that meant starting the entire process again.

The strangeness wasn’t lost on Scott: Hollywood’s future was being built with tools from the past.

However, it was a tour of the coveted Skywalker Ranch that revealed ILM’s true strangeness.

Set on 3,000 acres of manicured fantasy in Nicasio, CA.

The Victorian “main house” and Deco “tech building” were presented as century-old heirlooms but someone quickly pulled Ross aside and let him in on a secret:

“This is all fantasy. The buildings were just built in the ’80s.”

“This is fucking Westworld” Ross recalled.

But like Westworld, the ranch had rules.

In a 300-seat theater, he once saw a lone figure in the back. “Shhh,” someone warned. “That’s George. Nobody talks to George. If you pass him in the hallway, don’t make eye contact. Don’t ask questions.”

Scott had made it inside the Grail. The most celebrated dream factory on Earth. But to Scott it felt less like a studio and more like an amusement park built on shared delusion, ruled by a phantom king you weren’t allowed to look at.

That funky green carpet back at Kerner Boulevard suddenly felt less welcoming.

Worse, once the awe wore off, Scott discovered that for all his lofty title, he had no real power.

He could see the cultural rot, the financial pressures and technological lag. But he didn’t have the authority to fix any of it. If he wanted to survive he’d have to play the game differently.

So he began to plot.

The Kerner Manoeuvre

Ross sketched out a reorganization.

Similar groups within Lucasfilm would be clustered together under senior executives which streamlined decision-making. In this plan, ILM would be bundled with Skywalker Sound and a new Commercials and Attractions unit Scott wanted to develop.

He presented the plan to his boss, Warren Franklin, then VP and General Manager of ILM, framing it as a solution to Lucasfilm’s structural problems.

Lucasfilm approved and Franklin was promoted to Senior VP to oversee the newly formed division.

That meant Franklin’s old role, General Manager of ILM, was now Scott’s for the taking.

Years later, he admitted the move was anything but accidental. “I can fess up to the fact that I had pretty much orchestrated Warren’s ‘promotion’ to be fully in charge of ILM.”

The Empire Strikes Out

By ‘89, Scott was now the GM of ILM, who were cementing their status as the undisputed kings of visual effects in Hollywood. But the kingdom was in disarray.

Tech was frozen in the analog past, and finances were propped up by the deep pockets of its absent founder, George Lucas.

Scott was now in a position to fix it.

He had orchestrated his own promotion to get the power he needed, and was ready to start a revolution. He just didn’t realize that in the quiet, cardigan-clad halls of Skywalker Ranch, the Empire was already planning its counter-attack.

The Rebel Alliance

Scott’s first target was tech.

ILM might have been the most famous VFX house in the world, but inside it was stunningly primitive.

An edict from Lucasfilm president Doug Norby made it worse by banning new gear.

The company was losing money, so the solution was to starve it further. To Scott, that was corporate malpractice.

“If you don’t keep up with the latest tech, you won’t have a visual effects business.”

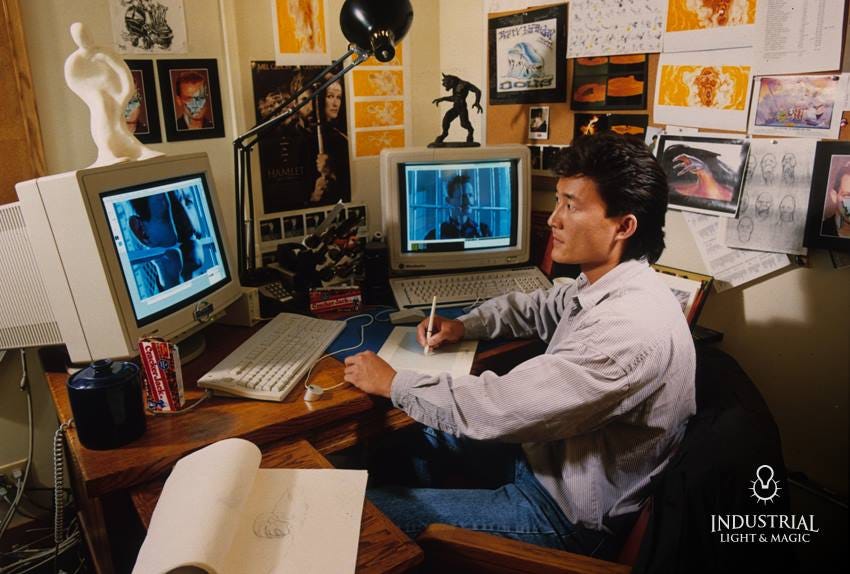

He knew he couldn’t fight alone. So he rallied the frustrated few, coining the crew the “Digerati,”. Leading the vanguard was:

Dennis Muren

Legendary VFX supervisor at ILM, winner of eight Oscars, key to Star Wars, Jurassic Park, and Terminator 2.

Scott Squires

Visual effects supervisor and technologist at ILM, pioneer in digital compositing and early VFX pipelines.

John Knoll

ILM VFX supervisor, co-creator of Photoshop, led groundbreaking work on The Abyss and the Star Wars prequels.

A small but potent rebel alliance. With them in his corner, Ross went rogue. He ignored the Ranch’s edict, stopped asking for budgets and simply started signing requisitions.

The payoff was immediate.

And historic. The gear he bought against orders directly enabled:

The first morphing sequence in Willow (1988)

The first digital full-screen composite in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)

The first CG character to show emotion, the water pseudopod in The Abyss (1989)

The first dimensional matte painting in Hook (1991)

The first CG main character, the T-1000 in Terminator 2 (1991)

Under Ross’s watch, ILM stopped being just a model shop and was becoming the launchpad for digital cinema.

Re-editing the Culture

Scott turned to his second target: culture.

ILM’s atmosphere was, in his words, “terribly depressed.” Staff were overworked, angry, and distrustful of management, mockingly dubbed the “Green Carpet Gang.”

“Green Carpet Gang,” seen as either out-of-touch suits or powerless figureheads enforcing a corporate will they had no part in shaping.

This wasn’t just an internal ILM issue; it was a direct reflection of its parent company, Lucasfilm. While ILM was the creative engine, Lucasfilm was the corporate mothership and the buttoned-down, top-down management style from “the Ranch” set the tone for all its divisions.

Scott’s fix was radical because it directly challenged this corporate culture.

He tore down the secrecy, hosting open noon meetings and weekly senior staff roundtables with one rule: argue all you want in private, but once a decision was made, everyone had to “sing a song of unity” to the employees.

He also became the artists’ champion.

When Disney refused to acknowledge ILM’s work on Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Ross fired back with this ad:

Disney’s ironclad rule was that nobody pulled back the curtain on “the magic,” which meant ILM couldn’t publicly take credit for the miracle at the heart of Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

Scott found a loophole. He retooled ILM’s logo, a magician pulling Roger Rabbit out of a hat by the ears and ran it as a full-page trade ad with the line: “Our Hat’s Off to Walt Disney Co., Robert Zemeckis, etc., on allowing us to part of the magic.”

It was a rebellion disguised as a tribute and Disney couldn’t complain without looking petty.

And most importantly, Ross was bringing rock ‘n’ roll to ILM.

Suit: The Sequel

Every rebellion must have its antagonist. And every company has its Suit. For Scott, that was R. Douglas Norby.

A Harvard MBA and ex-McKinsey consultant, Norby had stepped into the leadership void left by George Lucas’s retreat from public life.

To Scott, he was the embodiment of the anti-creative. And Scott’s success made him a threat.

He’d turned a money-losing division profitable, revived the culture, and won the loyalty of the crew. Firing Scott outright wasn’t an option. So Norby found another way.

The first move was a corporate checkmate: a “promotion” to Senior VP of LucasArts Entertainment. No raise. Just extra baggage: Skywalker Sound, EditDroid, and a pile of money pits that couldn’t get off the ground.

The final clash came over a bonus plan. Scott’s team crushed their targets, making ILM wildly profitable.

He drove to the Ranch, ecstatic, ready to share the news. “We did it!” he told Norby.

The reply: a long, cold stare. “The other divisions had failed” Norby said and the Board had decided: no bonuses.

For Scott, it was betrayal.

He’d made a promise to his team, based on a plan Norby himself had approved. He argued, pleaded and even offered to defer payments but Norby’s answer never changed:

“No.”

The Godfather’s Gun

That was the last straw.

Scott couldn’t work for Norby any longer so he went back to the Ranch planning to use his resignation as leverage but he was already out.

Scott left ILM with an unprecedented run of creative dominance, helping them win the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for five of the six films they completed under his leadership.

Oscar Winner, 1988: Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Oscar Winner, 1989: The Abyss

Oscar Winner, 1991: Terminator 2: Judgment Day

Oscar Winner, 1992: Death Becomes Her

Oscar Winner, 1993: Jurassic Park

But the dream had died and his reign as Pope had come to an abrupt end. The final, soul-crushing blow came a few weeks later.

Scott took his family out to a local Mexican eatery in Marin.

There, sitting at a table, was George Lucas himself. Scott cautiously approached to thank him for the opportunity he’d been given to work at ILM. George stared at him, his eyes blank.

“And you are? How do I know you?”

Six years. Five Oscars. A revolution. And the king had no idea who Scott was.

In The Godfather, Michael Corleone’s restaurant meeting with Sollozzo and Captain McCluskey is the moment he seizes power, a gun waiting in the bathroom to change his destiny.

But for Scott Ross, his own restaurant scene in Marin was the opposite.

Scott returned to his family table already a dead man. Erased from the Don’s memory of ILM, as though he had never been there at all.

To Scott, this was an insight into two things.

George was so incredibly far removed from the daily operations of the company that he was as likely to know who the GM was as he was to know the cleaner.

Doug Norby had done a masterful job of ring-fencing George from any communication.

Would it be so surprising to learn that this was only one of two times Scott would ever meet George face-to-face?

At the family table, he hit another problem.

How the hell do you get another job after being fired as Pope?

You don’t just browse the classifieds for “next ILM.” His phone barely rang and when it did, he almost wished it hadn’t.

One caller was Showscan, a location-based entertainment company. They offered him a role that he turned down flat.

Recalling it was “Like being asked to play for the Montana Mud Hens after you’ve played for the Yankees.”

The truth was..after you lead a company like ILM, there is no next job. You’d have to invent one.

But he also had a money problem.

His $125K salary might sound solid for 1993 money, but not for the GM of Hollywood’s biggest post-production house. And certainly not with two mortgages, private school tuition for three kids and a wife at the time who didn’t work.

The smart move was to take the Showscan gig. But you have to remember the second rule Scott would follow for the rest of his life.

He for sure wasn’t joining any kind of rat race.

The king might not have known his name, but Hollywood did. And Scott Ross was about to build a rival empire right on George’s doorstep.

Stay tuned for part 2 where we follow Scott setting up another company that would change post-production forever (again) but this time with none other than Hollywood heavy James Cameron.

Great read!