How a Stolen Print of Jerry Lewis’s Lost Nazi Clown Film Resurfaced 45 Years Later

The bizarre afterlife of Jerry Lewis’s forbidden Holocaust clown movie and the thief who claims to have kept it alive.

The Film No One Was Supposed to See

For half a century, The Day the Clown Cried has haunted Hollywood.

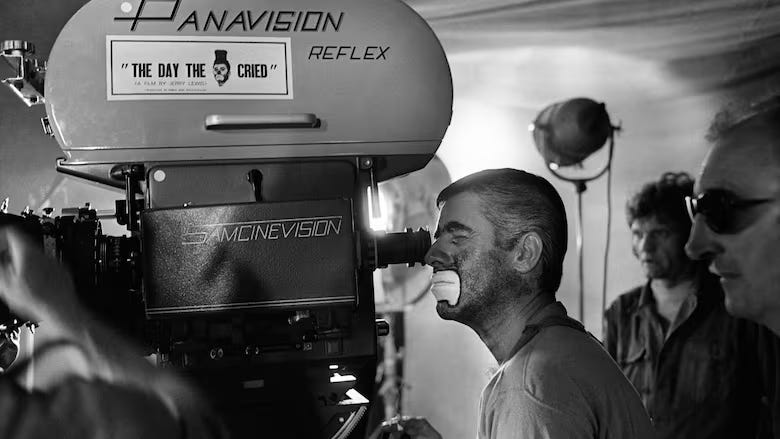

Jerry Lewis, one of cinema’s most beloved comedians, wrote, directed, and starred in the 1972 drama about a circus clown imprisoned in a Nazi camp who entertains children as he leads them to the gas chambers…

Yeah..

It’s regarded as one of the worst movies of all time. For the lucky (or unlucky) few who’ve seen it.

One of the few, was comedian and actor, Harry Shearer and he put it bluntly:

“Seeing this film was really awe-inspiring, in that you are rarely in the presence of a perfect object,” he said. “This was a perfect object. This movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is.”

So it wasn’t just bad. It was sublimely bad.

In a way that made it irredeemable to change.

Jerry agreed and locked the prints away, declaring it unfit for release and for decades it became the most infamous lost film in history.

The Myth Grows

Critics speculated whether it was simply unwatchable or too offensive.

Lost media circles treated it as the “holy grail” of cinema obscurity, a work of misguided ambition that could never live up to its own legend.

Fragments of The Day the Clown Cried have leaked out over the years, including the 1980s, when multiple drafts of the screenplay circulated amongst collectors and critics.

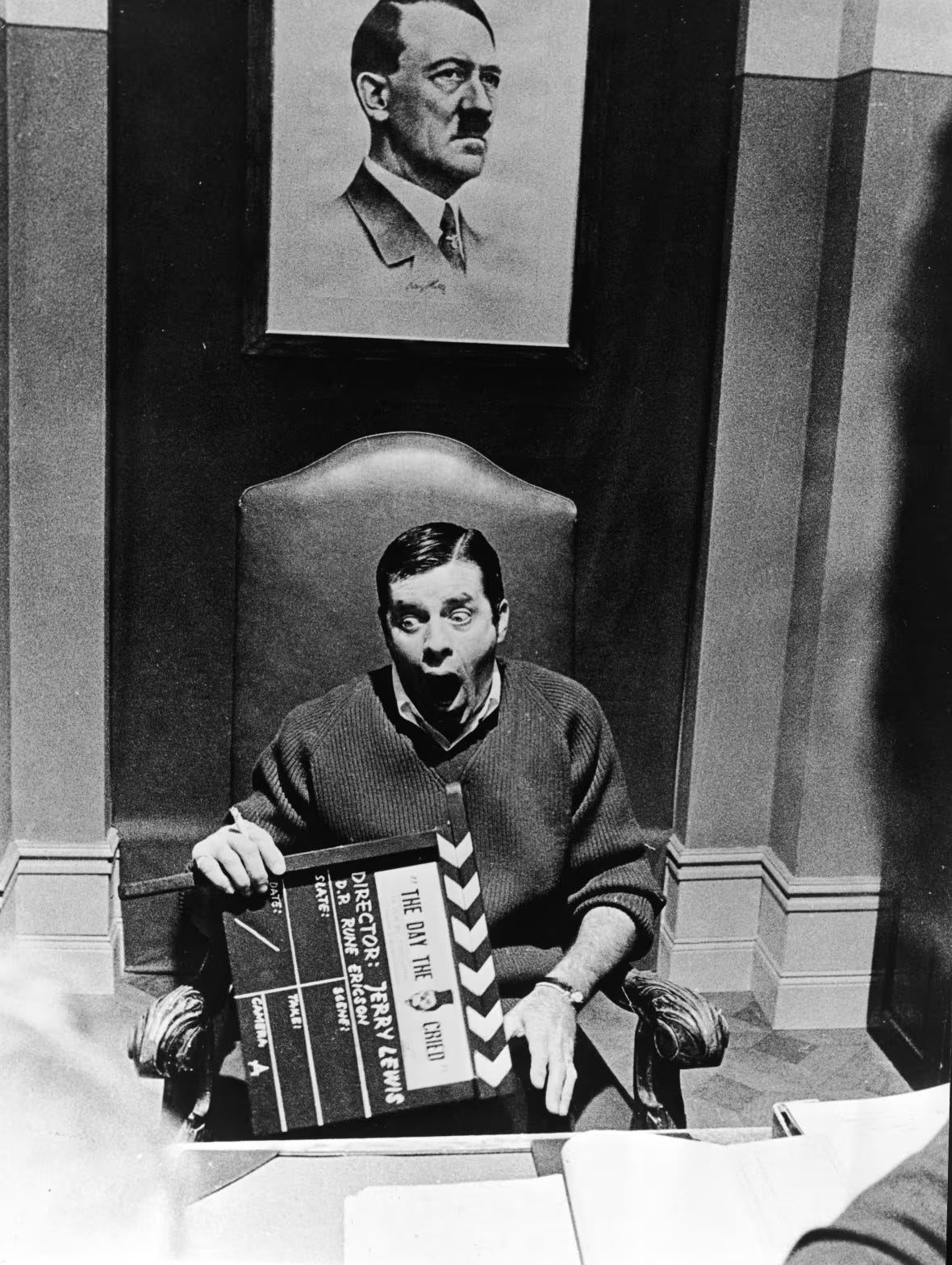

Production stills surfaced too. Blurry, unsettling images of Lewis in full clown makeup, walking with children through barbed wire fences, or sitting in despair in a prison cell.

Then, in 2015, the German broadcaster ARD aired a TV documentary called Der Clown, which included a handful of clips from the film itself.

For the first time, audiences saw actual footage: Lewis in costume, juggling for children in striped uniforms, scenes from the camp interiors. These brief moments, ripped out of context, only deepened the film’s mystique.

A year later, in 2016, the Library of Congress revealed it had received five hours of Clown Cried material, donated by Jerry Lewis himself in 2014.

But there was a catch: the contract stipulated it couldn’t be shown publicly until 2024.

And, crucially, archivists clarified it was not a finished film but reels, rushes, and rough assemblies.

2024: The Library Opens Its Vault

In August 2024, the stalemate seemed to break.

Journalist Benjamin Charles Germain Lee was granted a rare viewing of The Day the Clown Cried at the Library of Congress, the first outside eyes in decades to see the reels Jerry Lewis had deposited.

What he found was not the forbidden finished film of legend.

Instead, the archive contained reels of raw footage, partial assemblies, and test cuts. Scenes cut off abruptly. Dialogue was missing or unfinished.

In some cases, the same scene appeared in multiple, slightly different edits.

Lee reported that the five hours of material didn’t add up to a coherent whole. For myth-hunters who had long pictured a complete film lying in wait, this was both revelation and disappointment.

The truth was that the Library held only fragments and was fundamentally incomplete.

What Was in the Vault?

When archivists finally made the footage accessible to the public in September 2024, the holdings included:

~90 minutes of raw, silent color “dailies” uneditable takes shot during production.

~106 minutes of rough audio reels, disconnected from any complete visual structure.

~3 hours of behind-the-scenes material, plus sets of production notes and documentation.

2025: The Curious Crispin Case

Then came the twist.

On May 28, 2025, Swedish outlets Icon Magazine and SVT’s Kulturnyheterna dropped a bombshell: Hans Crispin, a minor Swedish actor and TV personality, claimed he had been sitting on the only known complete copy of The Day the Clown Cried for forty-five years.

Like something out of a heist comedy.

In 1980, while working at Europafilm, mostly transferring porn films to VHS, Crispin said he and a colleague smuggled out the eight Swedish reels of Lewis’s Holocaust drama.

A decade later, a former co-worker slipped him the missing French opening act.

Together, he said, these reels formed a full workprint with intact editing and sound and he kept it hidden ever since.

Crispin invited Icon journalist Caroline Hainer and SVT’s reporters into his home, screened the film for them, and told the story of his decades-long secret.

Overnight, the revelation made international news, picked up by Newsweek and Vulture.

For film fans who had long believed Jerry Lewis’s own Library of Congress donation was just scraps and rushes, Crispin’s pirate copy represented something more tantalizing: a supposedly complete version of cinema’s most infamous lost film.

And then came the kicker.

A few weeks later, on June 17, Crispin told Kulturnyheterna that he had sold the copy. “I received a modest sum,” he admitted. “They came here and watched it. They made an offer. I accepted it, signed a paper, and promised not to tell anything more.”

Right...

Crispin shrugged: “Yes, I stole it. I did. And I’ve thought about it. You’re not supposed to do that. But I really wanted to preserve it.”

Caroline Hainer herself has since been blunt. To her, the film isn’t the misunderstood masterpiece myth might suggest.

“It’s a bad film,” she told SVT. “Of course there are financial interests. Jerry Lewis was one of the biggest comedians in the U.S. in the 1950s. I guess it has fallen into the hands of someone who wants to distribute it. I would say there’s a risk that the public might see it. But it’s still a bad film.”

That’s one verdict. But the bigger question is: does the Crispin story itself really add up?

It Doesn’t.

Here’s why:

Ghost screening. Crispin “showed” the film to journalists, but no footage or verifiable stills have surfaced beyond that claim. We’re asked to take it on faith.

Suspicious sale. It’s been “sold” for a “modest sum” to someone who will remain anonymous. Convenient. We’re supposed to believe this buyer also cares as much about preservation as Crispin does.

Statute of limitations, limitations. Crispin told reporters: “I looked up the statute of limitations a long time ago. Two years.” But this isn’t a theft case anymore; it’s a copyright issue. And copyright doesn’t expire after two years.

Copyright fog. In the U.S., copyright is automatic once you create a work. But formal registration usually happens with release prints, with a © notice in the film itself. No one has ever found a record of The Day the Clown Cried being registered.

The workprint problem. Even if Crispin does have a copy, by all accounts it’s a rough, incomplete workprint. Not a finished movie. At best, it’s the same stitched-together fragments the Library of Congress has, just smuggled on different reels.

Final Frame

If Crispin is really telling the truth, the logic doesn’t track.

Why would he have a fully edited, coherent workprint when Jerry Lewis himself, the director, star, and gatekeeper of the film, only deposited fragments and rough assemblies with the Library of Congress?

If Lewis never finished it, how and why would a lab tech in Sweden be sitting on a “complete” cut?

Either Crispin is exaggerating, or Lewis deliberately withheld the supposedly finished version while donating scraps.

But here’s the caveat.

It’s also very hard to believe that reporters from a Swedish state-owned broadcaster and a veteran film critic would flat-out fabricate having seen the whole thing.

Something was screened for them. The question is what.

And whether it truly constitutes the mythical finished Day the Clown Cried, or just another stitched-together workprint masquerading as a lost masterpiece.

Whether the buyer ever screens it or whether it remains locked away, one truth is clear: the myth will continue.

And judging by the 53-year wait and the verdict of those who have actually seen it, chances are it won’t be worth it.