One Edit After Another: Andy Jurgensen’s Masterclass in Momentum

How Paul Thomas Anderson’s editor made a 2½-hour epic feel like 25 minutes.

Hi everyone —

Happy Thursday from VidSummit in Dallas, TX.

A few things stood out to me:

Creators are really optimistic about their future. The advancements in tools and new distribution avenues are a source of excitement.

The “creator economy” is real: there are legit businesses being created and transactions happening on top of today’s video platforms. People have full time livelihoods making YouTube content. A lot of people use YT/their videos on YT as a growth channel.

Admiration for YouTube as a platform and what they’ve catalyzed. See the point above, enabled by YouTube, much of which YouTube doesn’t directly take a cut in (eg brands sponsoring creators).

People do not see the “creator economy” as zero sum. People are excited to make intros, help each other out, and pay it forward. ‘All boats are rising’ mentality. Reminds me of Silicon Valley.

I’ll share reactions to our talks at VidSummit next week once I am back home.

Enjoy today’s newsletter.

—Shamir

PS: we just launched the new Feedback mode in Eddie where Eddie gives you feedback on your edits and how to improve it for better performance on YouTube. You have to try it to believe it. Launch video is here. Download Eddie here.

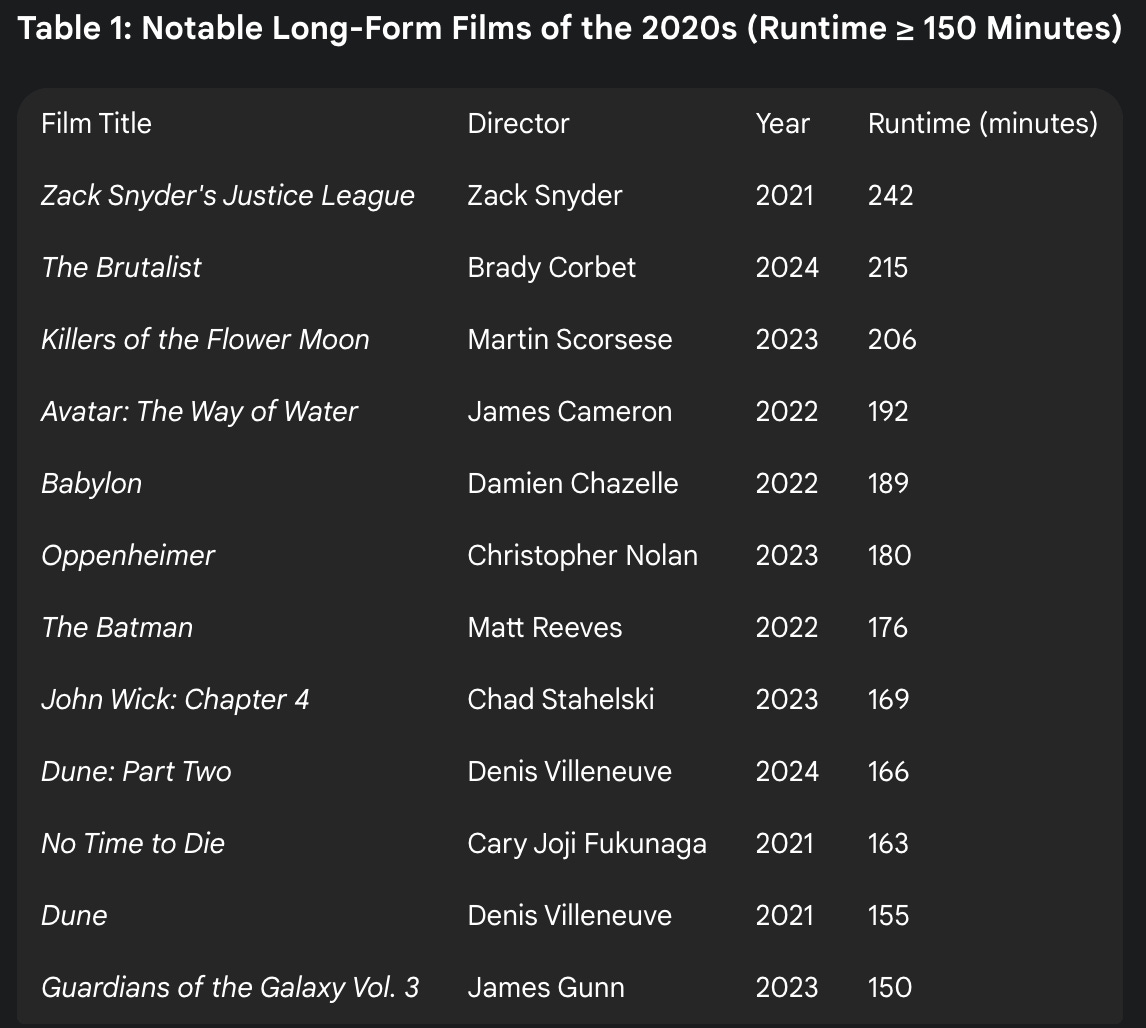

We’ve been living in the age of the three-hour movie for a while now.

Where formidable runtimes like Oppenheimer’s 180 minutes and Killers of the Flower Moon’s 206 minutes have become the norm.

This trend isn’t an accident.

It’s the direct result of a perfect storm of technological, economic, and cultural shifts that have fundamentally reshaped how we watch films. But as runtimes ballooned, so has narrative bloat and audience fatigue.

Then a film like One Battle After Another comes along. The new satirical thriller from one the greatest directors of our times: Paul Thomas Anderson.

At 162 minutes, it sits firmly in the “long movie” camp yet it many critics and casual filmgoers alike have noted its unrelenting pace.

The film is the exception that proves the rule: length isn’t the enemy, lazy pacing is.

To understand how we got here, we first have to break down why movies are getting longer.

Then we’ll dive into how One Battle After Another’s editor, Andy Jurgensen, crafted a 2.5-hour modern epic that feels half as long.

IF YOU HAVEN’T WATCHED THE FILM…. GO DO THAT. Then come back.

There will be spoilers in this letter :)

The epic runtime isn’t exclusive to Hollywood blockbusters. International and arthouse directors like Ruben Östlund (The Square, Triangle of Sadness) are part of a global wave of filmmakers also using length as a threatical draw.

Notable Long-Form Arthouse & International Films

The Square (2017, Ruben Östlund)

142 minutes

Triangle of Sadness (2022, Ruben Östlund)

147 minutes

Anatomy of a Fall (2023, Justine Triet)

151 minutes

Drive My Car (2021, Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

179 minutes

The New Epic: Why Every Movie Is So Long Now

The move toward longer films is driven by four key forces:

Digital Greenlight

For most of cinema’s history, film length was constrained by the tyranny of the reel. A standard 35mm reel held about 11 minutes of footage, and every additional minute meant more film stock, more processing, and heavier shipping costs.

Then digital arrived.

Shipping a three-hour file costs the same as a 90-minute one. And while every extra take still burns crew time, the hard costs of stock and reels are gone.

That freedom is liberating but it also removed the economic pressure to be concise.

Grandeur

To compete with streaming, cinema has repositioned itself as a premium experience.

Runtime can be a signal of ambition. Would a 90-minute Scorsese feel like an event? Probably not. Length telegraphs scope, scale, budget, ideas and importance. It cues audiences to treat the release as an event and not background content for a phone, iPad, or couch.

Longer runtimes also pull viewers into premium formats (IMAX/70mm) which help justify theatrical pricing in a shaky economy. Length also steers the critical discourse toward “serious cinema” and gives audiences more substance to engage with.

Saga Storytelling

Cinematic universes have turned storytelling into multi-film sagas. A movie like Avengers Endgame which services a dozen character arcs is an impossible task in two hours.

Endgame ran 181 minutes and served as the 22nd MCU film, paying off arcs seeded across 20+ prior entries. Its “time heist” chases 6 Infinity Stones across 3 eras via 5 concurrent missions (New York, Asgard, Morag, Vormir, plus a 1970 detour), culminating in an ensemble finale with dozens of heroes.

Despite the runtime, it (briefly) became the highest-grossing film worldwide, nearing $2.8B, which supports the idea that length = event.

Prestige TV Effect

The golden age of television reconditioned audiences. Viewers who binge eight-hour seasons of The Sopranos or Game of Thrones now have a taste for long-form, novelistic storytelling.

To compete with that depth, films have borrowed TV’s structure embracing extended runtimes to explore character and theme with a slower pace once reserved for the small screen.

One Battle After Another: The art of making 162 minutes fly

So how do you make a 2.5-hour movie that feels like it flies by in a third of the time?

First things first: no amount of clever editing can turn a sluggish story into a pacy one. Pace starts on the page, with stakes and purpose.

Pace = presence.

It’s about making the audience feel like they’re inside the moment, not just watching it unfold. That comes from characters we care about, and clear reasons why what matters to them should matter to us.

(Feeling like our protagonists could die at any time doesn’t hurt, either.)

Editor Andy Jurgensen, a longtime collaborator of Paul Thomas Anderson, recently spoke with The Film Stage and The Rough Cut podcast (not our pod although ours is coming soon) about how One Battle’s pacing was built.

SPOILERS INCOMING

Prologue as a Slingshot

Jurgensen’s goal was to make the opening as dynamic as possible using hard cuts and abrupt sound shifts to throw the audience straight into the story. The prologue originally ran longer but was pared down to its most impactful form.

The aim was to introduce Perfidia (played by Teyana Taylor) with maximum force, then signal that an entirely different movie is coming.

A Single, Decisive Cut

One of the film’s most striking moments is a single cut that bridges a 16-year gap. Baby Willa to teenage Willa, mid-karate class set to Steely Dan’s “Dirty Work.”

There are no title cards or expositions. But we instantly understand how much time as passed.

Jurgensen says this was always the plan; as no “in-between” footage was ever shot. The cut and cue do all the storytelling. It’s a perfect example of trusting the audience and letting one bold edit replace a montage.

Music as Motor

Whether it’s a needle drop or Jonny Greenwood eclectic, unrelenting score One Battle’s music is constantly driving us forward.

Steely Dan marks the shift from Act I to II; the Jackson 5’s “Ready or Not (Here I Come)” kicks off Act III as Bob escapes the hospital. These songs act as narrative hinges that reset audience energy.

There’s a thirty-minute stretch where Sensei shelters Bob as Lockjaw’s forces close in. Greenwood’s score ticks through it like a metronome. Steady and unrelenting.

Most thrillers use this kind of rhythm to build tension, then pull back for release.

But here there is no release.

The pulse trains us to expect something monumental but we just don’t know when.

“Peaks and Valleys”

Saying that, relentless motion can be exhausting.

Jurgensen understood the need for contrast with moments of rest that making intensity land harder.

He paced the film with quieter, character-focused scenes: a comic breakfast-table argument between Willa and Bob or tender car conversations before chases.

These valleys give us space to breathe allowing the highs hit harder because of them. As Jurgensen puts it, “you need to have a river of hills.”

Orchestrating the Chaos of Action

The final car chase sequence is a masterclass in controlled chaos.

Jurgensen’s team began by sorting footage by perspective: front of Willa’s car, rear shots, Tim’s car, Bob’s car then built the sequence piece by piece, tracking geography and momentum.

The aim was to bring the audience to the verge of motion sickness without crossing the line.

Andy Jurgensen: 9 Pull Quotes from the Cutting Room

On finding the tone

“I expected it to be serious… then realized it’s a satire.”

On PTA’s process

“Paul doesn’t tell you what he’s emulating, he wants to see what the movie becomes.”

3. On the big-screen format

“This is the first IMAX narrative presented in 1.43:1 the entire time.”

On the hybrid workflow

“We hauled a VistaVision projector on location and matched film dailies to digital on an iPad.”

On pacing philosophy

We were always asking: when do we let the audience breathe?

On the prologue

“The entire opening was reshot mid-production because PTA “felt it in his gut that he could do it better.”

On the DNA scene

“There are probably 80 versions of that scene.”

One of the hardest sequences to cut. Originally much longer, with a line that said, ‘It’s going to take 30 minutes.’

They cut it because, as Jurgensen put it, “When an audience hears that two hours in, they think, are we really sitting here for 30 minutes?”

8. On time/place ambiguity

“It’s modern, but not specific. An alternate present with wiggle room.”

On a personal fingerprint

“I did the titles myself. My partner laser-cut the logo and screen-printed it so it had real texture, we rescanned that and put it in the movie.”

One Battle After Another shows runtime is secondary.

Pace comes from story and edit working in sync. Jurgensen’s cut is the memo: match the story to the edit, throw us into the chaos, and let the cut tighten its grip until the credits hit and we finally exhale.