Scott Ross’ and James Cameron’s Pirate Ship: The Impossible Voyage and the Multi Million Dollar Iceberg (Pt.2)

Million-dollar compromises, a business model from hell, and the impossible partnership that revolutionized Hollywood.

Hi everyone —

I’m excited for today’s story. If you’re new here, our long form articles seek to tell the stories of the movers and shakers who sought to push video production forward, and by consequence or because of, push storytelling forward.

A quick update on Eddie, first.

We announced a meaningful update to Scripted mode yesterday (thanks No Film School for covering it). Scripted mode is intended for linear recordings — think straight-to-camera, like YouTube videos, educational content. (If you’re looking for edits with a narrative arc from interview soundbites, use the Chat & Edit mode to create a rough cut.)

What’s new in Scripted mode:

You don’t need a script anymore. (We should probably change the mode name ;) ) If you have a script or outline, add it.

Better take selection. Better story structure.

Robust text-based editing is here! See the chosen take, see the alt takes, move segments around. As before, when you’re happy: seamless export to your NLE

Doubled the input duration to 2 hours in this mode.

Expanded the number of supported languages to 5 in this mode. We support 30+ in other modes.

This update also adds support in Eddie for:

Add a treatment or brief guide to your edit

Colored and interpreted B-Roll now seamlessly Log and Relink in Premiere Pro

Multi-file, multicams in Final Cut Pro support

A new “Start Project” flow to make it clearer what Eddie does and for what type of projects.

Let me know what you think.

Enjoy today’s story.

—Shamir

Previously on The Rough Cut

Scott Ross was a Bronx kid turned rock ’n’ roll roadie who managed to talk his way into Industrial Light & Magic and dragged them into the digital age.

He rallied ILM’s underground tech rebels (the Digerati) and defied Lucasfilm’s equipment ban, greenlighting the tech that won ILM five consecutive Oscars: Roger Rabbit, The Abyss, T2, Death Becomes Her, Jurassic Park.

Then came the fall.

The ‘Green Carpet Gang.’ A corporate cold war with Lucasfilm president Doug Norby. A war Scott lost, ending with him exiled from the empire he’d helped build. The final dagger came weeks later when Scott spotted George Lucas at a Mexican restaurant in Marin County,

He walked over to thank him but Lucas stared back, blank.

“And you are?”

A line delivered with the casual cruelty of a Corleone.

Six years. Five Oscars but the king couldn’t remember his general.

Now Scott faced the one fate he deemed worse than death: being broke. But this wasn’t his end. It was the setup for the sequel.

Welcome to Part 2.

Trilogy by Fire

Scott technically wasn’t fired from ILM but he was promoted out of existence. One day he was making history; the next, he was history.

The job offers never came. Neither did the phone calls.

Until one did.

Showscan.

A call that felt like hitting the minor leagues after playing the majors. Scott’s answer was a resounding “no”. He was becoming a ghost in his own town, a pariah in Marin County who had committed the unforgivable sin of losing the best job in the world.

His severance was ticking down, counting the days until mortgages and private school tuition would rinse him clean.

When he finally hit the ground, the impact looked like friendly advice.

Ted Moehnke and Dickie Dova, his old ILM union buddies, dropped by. One of them gestured around the house.

You know, all you really need is to… downsize.”

Sell the Porsche. Find a smaller place.

The words landed like a lit match on gasoline.

Hell, no.

Scott decided to make a desperate decision. If Hollywood wouldn’t give him a job, he’d build one himself.

A job that could rival ILM. At a company that could rival ILM.

The first name he chose was ‘Phoenix Effects’ but he couldn’t rise from the ashes alone.

Devil’s Dowry

To take on ILM’s arsenal, he needed a weapon and it had to be nuclear.

He needed a partner whose name alone could bend the industry. Someone whose signature could greenlight the impossible. Someone who could scare the Skywalker Ranch suits.

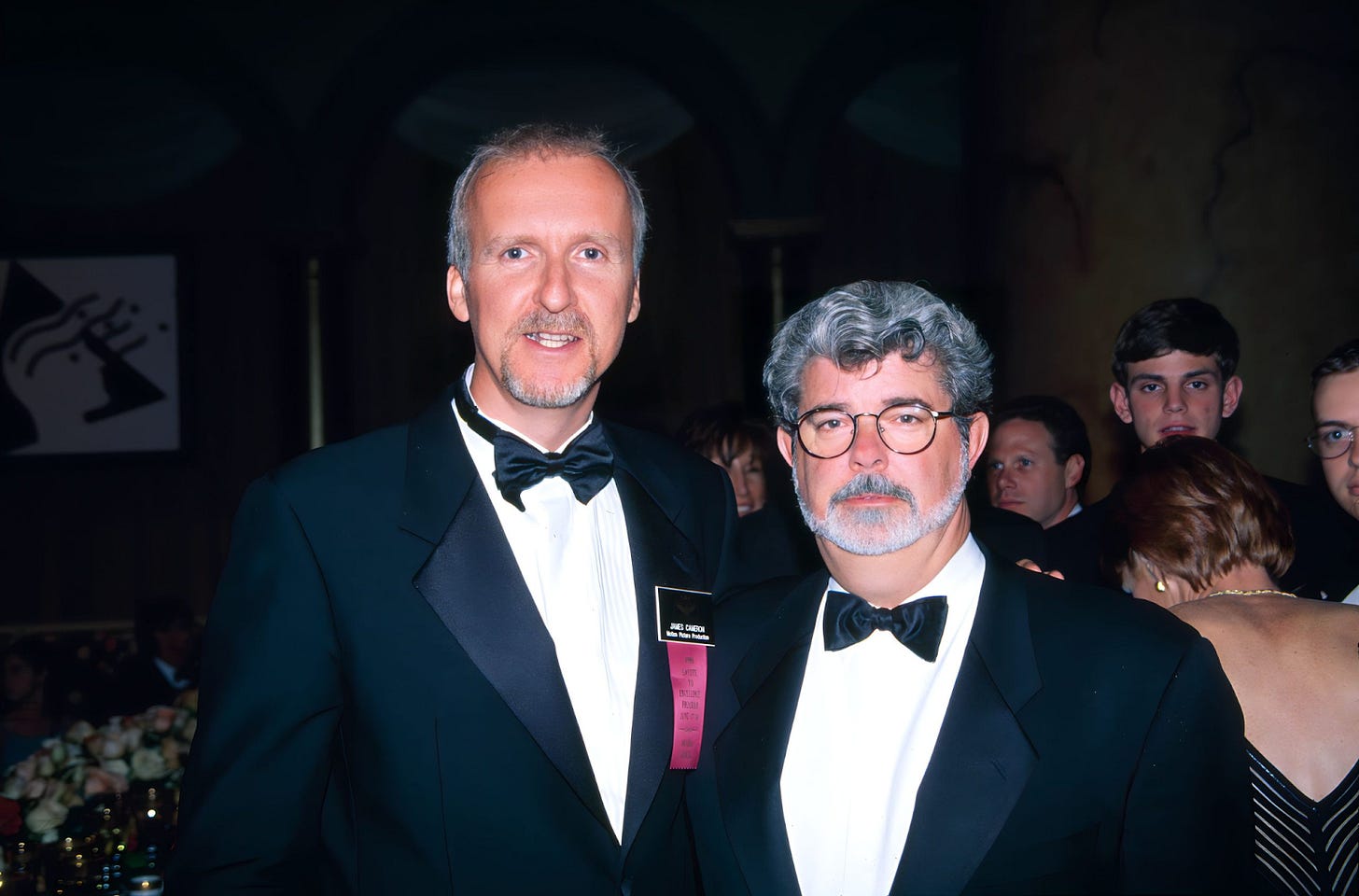

Only two men on Earth fit the bill. He’d already worked for the first. So he went for the second.

James Cameron.

If Lucas was a phantom king, ruling from a distant, manicured fantasy, Cameron was a warrior poet who lived on the battlefield. Scott was trading one impossible boss for another.

Conflict with Lucas was a cold war fought against corporate but the battle with Cameron would be a nose-to-nose brawl with a fellow artist. And a genius. In multiple domains.

The legend is true: Cameron was a truck driver who, after seeing Star Wars, quit his job and willed himself into becoming a filmmaker. He didn’t go to film school; he went to the USC library, photocopying graduate theses on optical printing and film tech to build his own education.

He started his career not as a director, but as a craftsman: a miniature model maker, a production designer, a matte artist. Working for Roger Corman, he famously built spaceship corridors out of spray-painted McDonald’s containers, sleeping in the studio for weeks on end because the budget allowed for nothing else.

This background gave him an entirely different kind of authority than Lucas.

He was often the most knowledgeable technician, artist, and engineer in the room. Delegation was optional.

It was exactly that intensity, equal parts genius and tyranny, that made Scott pick up the phone.

Scott wasn’t a stranger with an elevator pitch.

As GM of ILM, he’d already overseen the impossible for Cameron twice: the liquid pseudopod in The Abyss and the T-1000 in Terminator 2.

So when Scott called, the connection was instant.

Both men wanted to fix the broken VFX pipeline: endless handoffs, creative disconnect, a sense that magic was being made behind glass.

Fresh off T2 and newly crowned king of the world, Cameron was intrigued at Scott’s pitch. He was done lobbing his vision over studio fences. He wanted to be in the kitchen, as a collaborator, not a client.

For Scott, hearing this was like a prayer being answered.

But entry into the court of King James came with conditions.

First decree: his creature-effects oracle, Stan Winston, would be a founding partner.

Scott agreed instantly. Winston was a brand name, an Oscar-winning artist whose involvement would lend the new venture immediate credibility.

Second decree: Winston witnessed extinction firsthand with Jurassic Park making his animatronic dinosaurs look prehistoric in more ways than one. Desperate to evolve, he poured over a million dollars into a herd of Silicon Graphics machines.

A potential partnership with Scott was a way out and he demanded that the new company buy the equipment from him.

All of it.

Scott was in shock. To bring his company to life, he had to buy the corpse of another man’s dream.

But he was trapped.

Without Stan, no Jim. And without Jim, no company.

And without a company, no comeback.

Scott wrote the check and from day one, Digital Domain was built on a compromise born out of desperation.

A marriage of convenience with a bill only he was footing.

Launching the Pirate Ship

Scott survived a gauntlet of 40 interviews to get to ILM. Now he was about to face another, this time over land, sea, and wire.

His ‘93 calendar read like a travelogue of “no”.

Los Angeles to San Jose.

San Jose to Seattle.

Seattle to Chicago.

Then back to New York.

He pitched in boardrooms at Apple’s Infinite Loop, SGI’s Mountain View campus, and Sun Microsystems in Menlo Park. Companies whose engineers were literally inventing the tech he wanted to use.

Yet every meeting ended with polite smiles and the same refrain:

We don’t finance production companies.

In Seattle, he met with Microsoft’s multimedia division, hoping Bill Gates’s new obsession with CD-ROM storytelling might open a door.

Their response was colder:

Visual effects aren’t a platform. They’re a service.

Turner Broadcasting, Phillips Interactive, Virgin Group. Hundreds of letters. AT&T, Nintendo, Viacom, Comcast. Intel, NeXT. A half-dozen private equity firms. 40-page business plan.

None worked.

We make chips, not movies.

Why would directors want to sit in front of a computer?

200 phone calls, 40 flights, and over a year of rejection.

Even with Cameron’s name attached and the promise of guaranteed work from future blockbusters, the idea of a fully digital studio seemed too abstract.

Too expensive, and most importantly, too early.

I had the King of the World and the Wizard of Hollywood on board and still couldn’t get a single suit to write a check.

The most revealing rejection came from EA. Its president, Larry Probst, pulled Ross aside after a successful dinner.

He was impressed, but had one major reservation.

“No one can control Jim Cameron. He’s unreasonable. He’ll do whatever he wants. I can’t have that in a public company.”

A warning of the problem that would later almost sink Digital Domain.

But Scott was already past the point of no return.

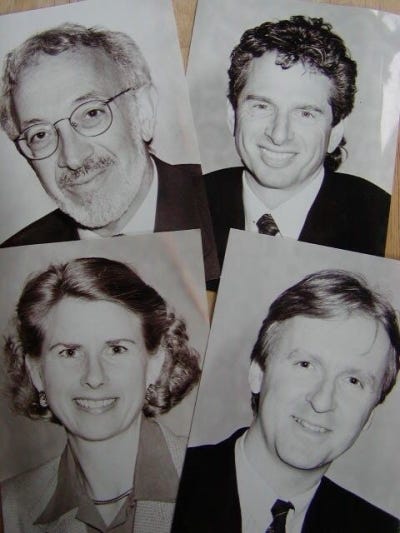

The Woman from Armonk

After a year of glassy-eyed “we’ll get back to yous,” salvation arrived not from Hollywood or Silicon Valley but from Armonk, New York.

Enter Kathleen Earley.

To Scott, she was something out of a corporate fever dream: sharp suit, sharper instincts, fluent in tech and power. A rising IBM VP known for cutting through bureaucracy like a scalpel.

When Scott pitched Digital Domain to her, she grasped instantly what most investors had missed. Scott was building much more than a vendor; he was building infrastructure.

Kathleen not only brought the deal to IBM, she brought IBM to the table.

And on that table sat $15 million for a 50% stake in Digital Domain.

At the press conference announcing the company’s formation, she stood shoulder to shoulder with Scott, Cameron, and Winston: the lone corporate exec among three Hollywood titans.

But the entire funding process had revealed the central problem.

The very thing that made Digital Domain irresistible to investors, Cameron, was also the reason they feared it. A creative force of nature is great for headlines but disastrous for boardrooms.

And disaster was certainly on the horizon. And in the water…

Martini Marina

With funding secured, Scott set out to build the company he’d always imagined. A creative pirate ship with no admirals, no green carpets, and no suits.

Digital Domain dropped anchor in Venice, California, inside the former Chiat/Day headquarters. Martini Mondays became ritual. Legendary parties featured Etta James and Dr. John. T-shirts read: Upstart.

Scott fused everything he’d learned from his two mentors: Taylor Phelps’s (his boss at One Pass) people-first spirit and the ruthless operational discipline of the suits he once fought.

He believed creative companies only worked when leadership was cut from the same cloth as their artists.

The Chaos Committee

While Scott was busy building culture, the cracks in Digital Domain’s foundation began to show.

The Operating Committee: Scott, Cameron, and Winston, was designed as a creative shield to protect artistry from corporate meddling. In practice, it was chaos disguised as collaboration.

We were meant to meet regularly. In reality, we met maybe four or five times in three years. And when we did, Jim and Stan spent the hour talking about Hollywood gossip and upcoming projects. Nothing got decided.

The first major test was Cameron’s True Lies. Cameron shed his ‘partner’ skin and reverted to ‘client.’ He hired the film’s VFX supervisor, John Bruno, without consulting Scott, a major no-no.

When production problems hit, Cameron didn’t call his partner.

He called 20th Century Fox, threatening to withhold payments that Digital Domain needed to make payroll.

To Scott, Cameron wanted all the perks of an in-house studio.

Creative control, discounted prices with none of the responsibilities. No concern for budgets, morale, or sustainability.

Outwardly, the pirate ship looked unsinkable.

True Lies earned an Oscar nomination on the company’s very first voyage.

But inside, the hull was splintering.

Digital Domain’s chairman was also its most demanding, financially punishing client. And soon, that conflict would find its perfect metaphor: a film about a ship fated to sink.

The Impossible Iceberg

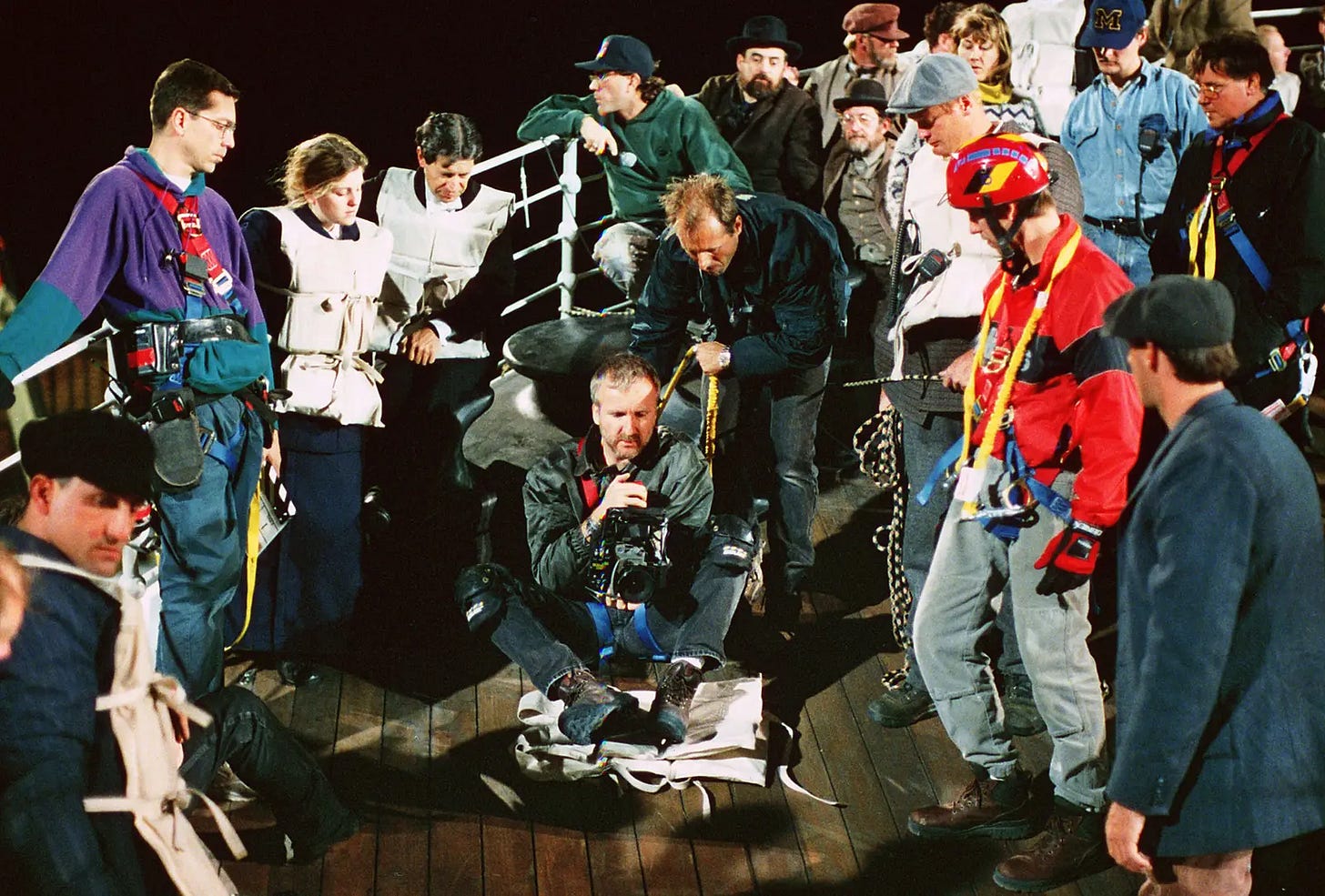

It’s early 1996 and Cameron brought his most ambitious project yet: Titanic.

He and producer Jon Landau arrived with a fait accompli: Fox had greenlit $18 million for visual effects.

Just one problem.

Digital Domain hadn’t been consulted and when Scott’s team did their own breakdown, the real cost was $27 million. A $9 million shortfall that could sink the company before the ship even set sail.

When Scott raised the alarm, Cameron didn’t flinch.

If you can’t do it for $18m, I’ll take it to ILM.

He wasn’t bluffing. ILM would eat the loss to cripple its upstart rival.

Scott put it bluntly:

If we didn’t take it, DD was out of business but if we did take it, we might still be out of business.

Scott signed the paper cueing the zeros to blur into an infinity he couldn’t afford.

Then came the slow-motion shipwreck.

Production ran two months behind, jamming the VFX pipeline and forcing brutal overtime. When Scott filed change orders, Cameron blocked them, using his power to overrule his own company.

And yet, you couldn’t deny what Cameron was building.

Titanic was an industrial miracle:

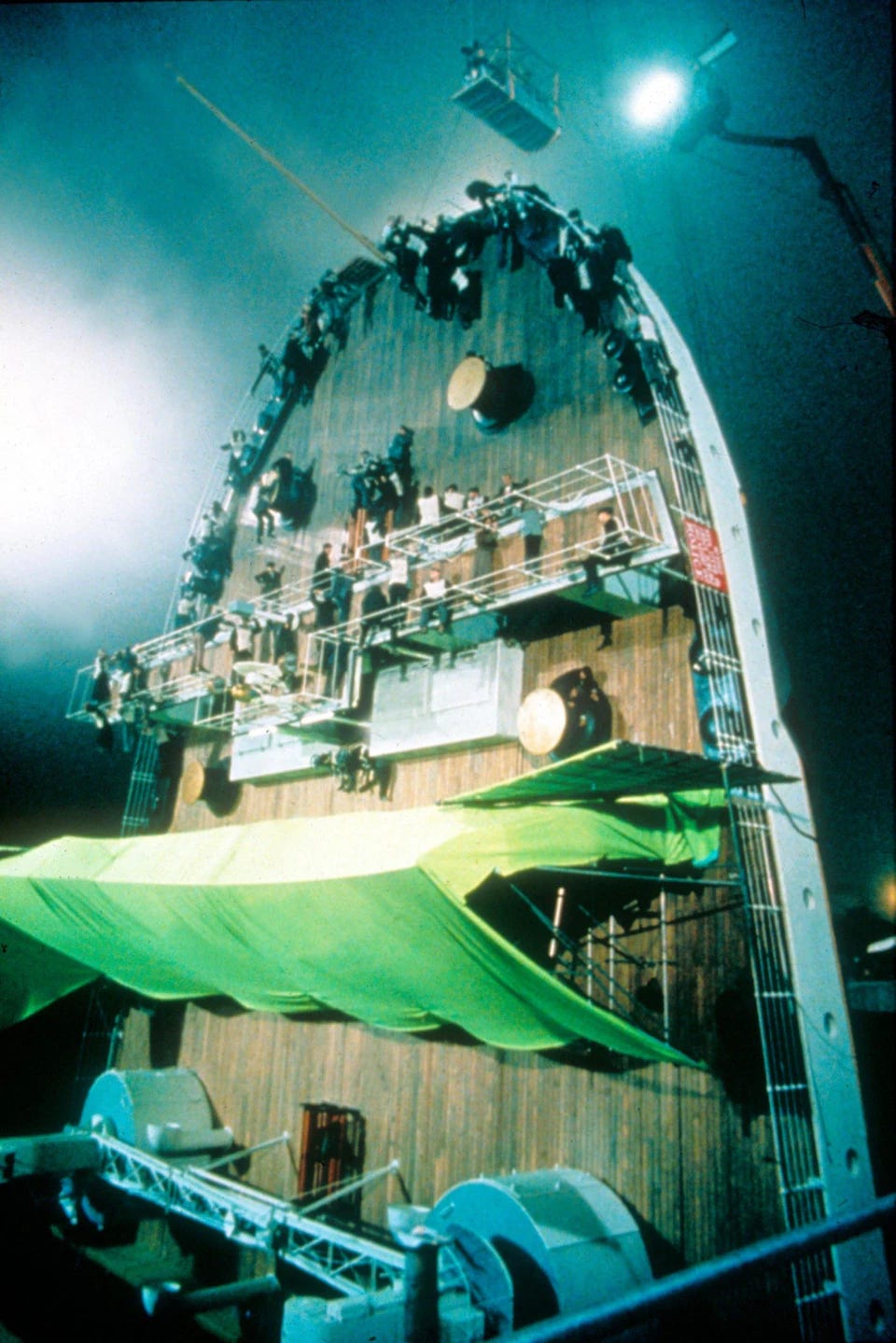

$200 million budget, 18,000 extras, 800 crew, 775 feet of ship, 160 shooting days.

All driven by one man, with Digital Domain in his shadow.

In Dartmouth.

In Rosarito.

In a purpose-built Baja studio with a 17-million-gallon tank and a near-full-scale replica.

Cameron even built the ship backwards so the wind would blow smoke correctly which required the entire image to be flipped in post.

Titanic was already making history well before wrap.

And then came the iceberg…

The Iceberg (For Real)

During the Dartmouth shoot, someone spiked the crew’s chowder with PCP, sending more than 50 people to the hospital.

In Rosarito, actors battled infection. Kate Winslet chipped a bone in her elbow and swore she’d never work with Cameron again unless she got paid a lot of money.

DiCaprio later said he regretted turning down Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights for the film.

Crew members nicknamed Cameron “Mij,” Jim spelled backwards and his evil alter ego, and Bill Paxton even called the set “Jim’s war zone.”

Post-wrap, the numbers were sinking faster than the ship.

Titanic’s bloated $200 million budget (about $400 million today) was clocking in at nearly $1 million per minute. Fox panicked, demanding an hour be cut.

I think you know what came next.

You want to cut my movie? You’ll have to fire me.

You want to fire me? You’ll have to kill me.

Fox gave up, choosing to partner with Paramount, trading domestic rights for cash.

Cameron even surrendered his $8 million salary and backend to keep the film alive.

Digital Domain was caught in no man’s land.

Titanic was both miracle and nightmare. A project that could make them and destroy them at the same time.

And just when Scott surfaced for air, the public humiliation arrived.

In an April 1997 Newsweek article, Cameron praised DD as “brilliant,” then twisted the knife:

Sometimes I think they’re idiot savants.

For Scott, that was the final straw..

He recalls they were “nose to nose, screaming at each other,” .

A showdown years in the making.

Cameron stood 6’2”, intimidating, but Scott figured he could take him as he was benching 220 at the time.

Days later, Cameron called an emergency meeting with Stan and Scott.

He declared Scott unfit to run the company and moved to replace him.

The vote: 2–1 against Scott. As always.

But when it reached the full board, something shocking happened.

The corporate backers (IBM and Cox Communications) revolted.

They sided with Scott and stripped Cameron of his chairmanship, making Scott the new chairman.

Cameron and Winston walked.

As Cameron left, he delivered one final line. One he wrote for another doomed ship:

Gentlemen, it has been a privilege playing with you.

The Lost Loot

There’s a beautiful irony about Titanic.

It grossed over $2.2 billion, becoming the highest-grossing movie ever at the time: a record Cameron would later break with Avatar’s $2.9 billion.

It won 11 Oscars, including Best VFX for Digital Domain. Yet it was a financial catastrophe.

Digital Domain lost millions on Titanic alone and had to lay off over 100 employees. The final insult: Fox reinstated Cameron’s back-end participation as a gift.

A single accounting change that wiped out any hope of DD recouping its losses.

Spoils of War

Digital Domain delivered some of its best work in the years after Titanic: Fight Club, The Fifth Element, What Dreams May Come, The Time Machine.

But behind the scenes, the same structural issue haunted them: the ‘business model from hell’ eating away at the company.

DD was winning Oscars, but barely making a profit on nearly every film.

The Last Voyage

By 2002, Scott’s ship had run its course.

The boardroom battles outlasted the glory years, and the business model that once made Digital Domain a revolution now made it untenable.

Scott resigned as Chairman and CEO. IBM and Cox sold their stakes, and the studio drifted through new owners, new eras, and eventually, bankruptcy in 2012.

But like its name, Digital Domain found a second life: a VFX powerhouse reborn from its own wreckage, working on blockbusters like Avengers, Captain America, and Dune.

After walking away from the front lines, Scott became one of the VFX industry’s most outspoken voices: consulting for studios and governments, lecturing at film schools, and campaigning for fair labor and a global VFX guild.

He’s a regular fixture on panels at SIGGRAPH, FMX, and VIEW Conference, warning about the ‘race to the bottom’ created by runaway subsidies.

In 2024, he self-published Upstart: a blisteringly honest memoir about ILM, Digital Domain, and the modern VFX revolution that inspired much of this series.

He now sits on Boards, lectures, consults and advises the next generation of artists, still challenging the system he helped build.

No longer steering the ship, but teaching others how to survive the next storm:the one brewing in the cloud, not the sky.…

If you’re like reading this please like, share and subscribe (if you haven’t already) ❤️