Star Trek, a Basement, and a Broken Spine: The Origin Story of Hollywood’s Favorite Editing Software, Avid

Where Bill Warner saw friction, he gave editors flight

Hi everyone!

I’ve been so excited as the research was happening for this month’s longform story, the story of Bill Warner and his company, Avid. Every video pro knows Avid. Few know its origin story.

Bill Warner is an unlikely founder who took on the entire post-production establishment with a sketchpad, a secondhand desk, and a belief that editing should feel as intuitive as writing. If you’ve ever dropped a clip on a timeline, you’re standing on his shoulders.

I worked on a documentary project years ago where we edited on Avid Media Composer. The software was difficult to grasp. And it definitely looked and felt outdated. Once upon a time, Avid was the most modern thing around and captivated the mindshare of the earliest of adopters and those who dreamed of a better way to edit video.

When I listen to Bill in his launch video from 1989 (!!!), it is eerie: he sees the power of video but it is too hard to bring to life. Sound familiar?

I hope you enjoy the story. Let me know what you think in the comments or by replying to this email.

Besides researching and writing this story, we’ve been working hard on June’s updates to Eddie, which we dropped on Tuesday. We just launched multilingual support in French, Spanish, and German. We also leveled-up both A-roll and B-roll logging: smarter clip detection (we choose the best subclip), bigger projects (up to 400 clips), and smoother multicam workflows. You can read more in our write-up from No Film School here. And ICYMI: last week we dropped a video for every editor quietly using AI. Watch it here.

Without further adieu, enjoy one of the wildest backstories in post-production: how a Star Trek fan, a basement in Boston, and a broken back led to the invention of Avid, the first nonlinear editing system.

—Shamir

PS Thank you Tom, Steve and others for sharing your wonderful gems of Avid’s early years as we researched this story.

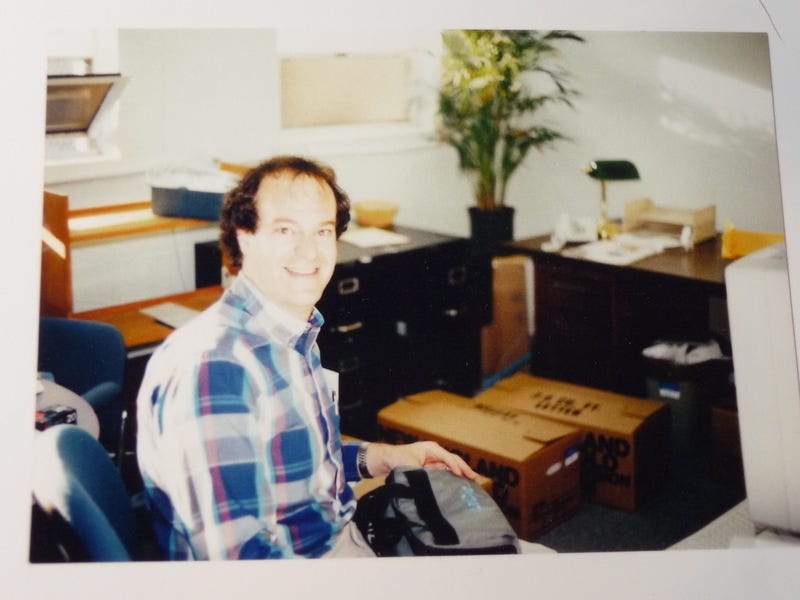

The walls were bare. Concrete floor, uneven.

A single phone line, borrowed desk, and the faint smell of rust still lingering in the air. If you had wandered into that disused machine shop in Boston circa 1988, you wouldn’t have seen the future of Hollywood.

You’d have seen a startup that barely qualified as a company.

Just two guys, Bill Warner and Eric Peters, crouched over mismatched monitors, surrounded by the whine of drives and the hum of ambition.

Warner had been working in marketing at Apollo Computer for 4 years when he ran into a problem. The company asked him to cut a promo video for their high-performance workstations, and he figured, how hard could it be?

Write the script, shoot footage, and maybe borrow an editor for a few hours. RIght?

Wrong.

Cue a week-long nightmare. The editing process was painful. What followed was bouncing between tape decks, linear systems, and a $3,000 bill.

He asked his colleague and engineer Eric Peters, a deceptively casual question:

“Why can’t we just do this ourselves?”

Most engineers would’ve laughed. Eric didn’t. He opened a notebook and sketched something radical: a video editing interface that worked like writing software.

Something nonlinear. Intuitive. Something you could do with a mouse.

They pitched the idea to Apollo’s top brass.

“Meh,” said Apollo.

And that was that.

So they quit.

No investment. No roadmap. Just a basement and a dream.

Family Vacation, a Camcorder, and a Perfect Crime

Bill got his first camera at age six. A Kodak Brownie. Later, an Instamatic. Then, at fifteen, a Nikon FTN metal, manual, and heavy in the hands. A camera that felt like graduating college.

Before there was Avid, there was Star Trek. Every Friday night, Bill Warner parked himself in front of the family TV, battling his sister over the dial.

She wanted courtroom drama. Bill wanted Captain Kirk. He won. Thankfully.

Because while Spock preached logic, it was Kirk, the swaggering idealist who followed his gut and came out on top.

For Bill that wasn’t just sci-fi. It was a blueprint. Even before he had the language for it, Star Trek was planting a seed: that great technology isn’t just about function.

It’s about feeling. Following heart over head.

But..Bill took his head to St. Louis. Literally. He majored in economics, not out of love, but logic. A “good thing to do.” He clipped Wall Street Journal articles, convincing himself that made him a serious student.

In truth, he was just inventing a version of himself he thought the world wanted.

Then came the ice. Then the tree.

Suddenly, he was in a hospital bed in New York City with a broken back and staring at a life he’d have to re-invent again.

At the hospital he met a guy called Tom Wade. Quadriplegic. Like Christopher Reeve, Tom couldn’t move his arms or legs. And yet, somehow, he moved something in Bill.

One day, Tom was on the phone with his girlfriend. Someone had cradled the receiver for him, but when it came time to hang up, he told the hospital operator: “No, I can’t. I can’t hang up the phone.”

And Bill thought: This is ridiculous. So he got to work.

He bought a whistle switch, one of those breath-triggered gadgets and rigged it up over Tom’s bed. Connected it to a light.

That moment lit the fuse. He spent the next few years building what he called the Whistle System: a DIY smart home for the paralyzed. Lights. Channels. Phones. All triggered with a puff of air. It wasn’t just a hack—it was a revelation. Technology could restore agency. Interface could equal freedom.

By 22, he’d dropped economics, enrolled at MIT, and locked in on one obsession: building tools that let people express themselves.

That early obsession would become the seed that grew into Avid.

Back at the Warner house…

When camcorders finally shrank enough to hold, he bought one for $2,000 ($6K today): a bulky battery pack on the hip and a lens the size of a Pringles can.

Then came a family trip to Palm Springs, California. Everyone was in town, siblings, cousins, the whole noisy Jersey clan.

Warner had an idea: script a heist comedy starring his nieces and nephews. He called it Take the Money and Run.

He wrote it. Directed it. Shot it. Then made one fatal mistake: he tried editing it.

Post-production back then meant sitting cross-legged in front of his parents’ fake fireplace, connecting the camcorder to their living room VCR. Two machines. No software. Every punch-in had to be perfectly timed or you start over.

They couldn’t watch TV for three days. He nearly gave up. Probably should have. But when he played it back, the joy in the room made it worth it.

And somewhere between the glitches and the rewinds, it clicked.

There had to be a better way to edit.

Now, by day, Bill Warner was in the marketing department at Apollo Computer, helping sell high-end workstations to engineers and scientists.

By night, a frustrated home video enthusiast, wrangling VCRs and cables.

But something was brewing.

The late nights, the notebook sketch, the leap into the unknown.

A question turned into a prototype.

The $300-an-Hour Lie

Before there was Avid, there was just pain.

Apollo had a rudimentary system, a Panasonic knob editor, but it was still tape.

One day, Bill pitched a bold idea to Apollo: skip the brochure, let’s make a video ad for our high-end graphics workstation.

Something slick. Something pro. And this time, Bill thought, he’d do it right with one of those futuristic “computerized” editing systems.

His boss signed off but what came next was less the future and more a $300-an-hour farce.

He called up a post house in Boston. “You have a computerized editing system?” he asked. “Sure do,” they said. “How much?” “$300 an hour.”

Bill winced but booked it anyway.

He arrived with a stack of tapes, no script, and a request: “I want to do it myself. Just show me the controls.” The tech shrugged, sat him down, and began. “P is play.” The screen flickered.

“Spacebar to stop.” Then came R. Rewind. Bill froze.

“Wait. Is that… a tape deck?”

“Of course,” the tech said, confused.

Bill blinked. “You said this was computerized.”

“It is.”

“You’re just… controlling tape decks?”

“Yeah.”

The air went out of the room. The promise of digital was a lie. All the blinking lights and green phosphor screens still boiled down to linear pain and mechanical rewind. You couldn’t jump. Couldn’t rearrange.

You couldn’t think.

Bill walked out certain of two things:

The system was broken (almost literally)

And he wasn’t waiting for someone else to fix it.

Houston, we have a blip

Bill decided to cut the whole promo video for Apollo himself. Punch by punch, rewind by rewind.

And somehow, it worked. Apollo loved it. So did customers who didn’t know polygons from pizza.

Just like that, sales videos became the go-to. Every new product needed one and Bill became Apollo’s unofficial video guy.

But trouble was afoot.

The briefs began to evolve but the budgets didn’t. Motion graphics. Glows. Effects. By edit ten, he hit a wall.

Then came the $600 million moment.

In 1985, General Motors’ tech arm, EDS, announced a massive workstation buy. Hundreds of units up for grabs. The bidding conference was packed, hundreds of faces in the room.

Bill was one of them, seated quietly in back.

When GM mentioned they wanted full-resolution video “in a window,” heads turned. Bill sat up straighter.

He had an idea.

Back at Apollo, he pitched the impossible: full-screen video on a 1280x1024 display.

Then he called a small hardware company, Parallax Graphics. They’d been dreaming of the same thing. He told them about the GM deal. “If you build it, we’ll ship it.”

They said yes.

Parallax made a triple-board set so power-hungry that Apollo had to build a new tower just to run it. Engineers nicknamed it “Giraffe” because of how far they were sticking their necks out.

But it worked. Apollo got the contract. And Parallax shipped the boards to others too.

Somewhere in the tech soup of power supplies, off-screen buffers, and early blit transfers, a thought crept into Bill’s mind:

If we can store video off-screen… and blit it fast enough… maybe we can edit. Not just 30 seconds. Not just promos. But long-form video.

I think you know where this is going..

Welcome to Avid. Watch Your Step.

It wasn’t a garage startup, but it might as well have been.

Bill’s actual basement served as the first lab. When they outgrew that, they didn’t lease the 80s equivalent of a WeWork.

They moved into an abandoned machine shop.

3 Burlingham Woods

They built their first “office” themselves. Eric handled the wiring. Bill patched drywall. They hung lights from old ceiling beams and hauled in secondhand desks. The heating barely worked and they had one single bathroom for the entire floor.

Avid Technology wasn’t a company yet.

They brought on Jeff Bedell, a young software designer with a knack for building intuitive interfaces, and within weeks, their Frankenstein system could play back low-res video clips on a screen.

Then came Joe Rice. Then Tom Ohanian. The team was five people deep, max. But in Boston’s small tech press scene, word got out.

Scott Kirsner from the Boston Globe was the first to stop by. “We think you’re onto the next big thing,” he told them despite not really knowing what that “thing” really was.

A Demo That Nearly Imploded

The real test came at NAB 1989.

The team showed up to the Las Vegas convention with a barely-working prototype. They were set to demo the very first version of what would become Media Composer. The booth was a rented table. The rig, overheating. The compression still looked like VHS on a bad day.

And then the machine broke. Hours before their slot.

The team scrambled. Jeff dove into code. Joe tried to track down spare parts. Warner begged the organizer for a delay. By the time the demo started, nobody had slept in two days.

But somehow, the Avid system ran.

It didn’t crash. Clips moved. Cuts played in real time. Editors who saw it stared slack-jawed at the screen.

“I can see the edit?” one muttered.

It was scrappy and fragile. Borderline held together with prayers and gaffer tape but it worked. The crowd didn’t just see software; they saw a future.

At that moment, Avid wasn’t just a prototype anymore. It was real. And the edit would never be the same again.

From Basement to Boardroom

But Bill Warner didn’t stick around to ride the wave forever. In 1991, just as Avid was rocketing skyward, he did the unthinkable: stepped off.

Mid-launch. Why? To chase another wild idea: voice-controlled computing. He co-founded Wildfire Communications, a speech-based assistant so ahead of its time, it made Siri look like a knock-off. Wildfire sold to Orange in 2000.

Then came FutureBoston, a digital archaeology project turned interactive atlas. Then a coworking hub in Cambridge before WeWork. Then the MassTLC Innovation unConference, flipping the script on startup gatherings.

These days, Warner’s full circle: helping founders go inward before going public. His initiative, Build Your Startup From the Heart, is part workshop, part philosophy.

He doesn’t just invest in ideas. He bets on people. Early. Sometimes before there’s even a product. If the spark is there, he’s in.

Avid in the Age of Cloud and Chaos

In year one Avid turned over $1 million in revenue.

Year two: $3 million.

Year three? $25 million.

Fast forward 35 years and you’re now looking at a yearly turnover of $360 million. Multiple Emmys, Oscars, and a name so embedded in the industry, Avid continues to be the go-to for Hollywood’s biggest productions.

What began in a Boston basement was now the trusted backbone of billion-dollar franchises and auteur-driven indies alike.

Avid’s influence on Hollywood became so foundational that you could argue they held a monopoly. At the 2018 Oscars, every single award nominee and winner in film editing, sound editing, sound mixing, and original song score was an Avid user. Yes, every single one.

Today, pretty much every high-end TV show or Hollywood film is still using Avid. Oppenheimer, Succession, The Bear, Barbie. The list is endless.

But there has been a vibe shift. Premiere Pro leads the prosumer crowd. Resolve is gaining ground and Final Cut’s still around. While Avid remains Hollywood king, in a current industry full of shakeups, even royalty can be replaced.

In 2023, Avid was acquired by private equity firm STG in a $1.4 billion deal, taking the company private once again. Some see it as a chance to innovate without Wall Street pressure. Others see a mature company tightening the reins on its legacy.

What happens next is anyone’s guess.

But what happened first: that’s the real story. Because if his sister had won that one Friday night TV standoff and they’d watched Judd, for the Defense instead of Star Trek…

Who knows what would’ve happened to the timeline: the course of history, and the one in your NLE.

I'm Dave Salamone. I was an editor at HBO Studios from '89 - '99. I believe I may have edited the first long-form project on an Avid. Play-by-Play: A History of Sports Television aired on HBO in 1991. Below is a link. Looking back, it wasn't my best work, but it did win me a Sports Emmy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9x1JUJnbi2A&list=PLgnKVFiG-uECl1qZrA7LisvrMvOvYzX0k&index=7