The Anatomy of a Great Trailer

From hype to heartbeat: Inside the craft of selling a film in 150 Seconds

Hi everyone —

Hope you’re having a great week. We just had a Halloween party at our office (incl for families) and now my kids are negotiating with me about how they should be allowed to eat even more candy even though they’ve had enough for a year or two.

To make matters worse. One of my kids correctly guessed “320.” The exact number of candies in the bucket. The prize, of course, is the entire bucket of 320 candies.

Wish me luck.

Eddie’s been busy! We’ve been rolling out small tweaks and improvements almost every day—little quality-of-life upgrades that make editing smoother and smarter. We also boosted the Plus plan to have even more editing credit per month.

But hold onto your headphones… next week, we’ve got a bigger update coming to Eddie AI. 👀

And what do you think of our new website?

—Shamir

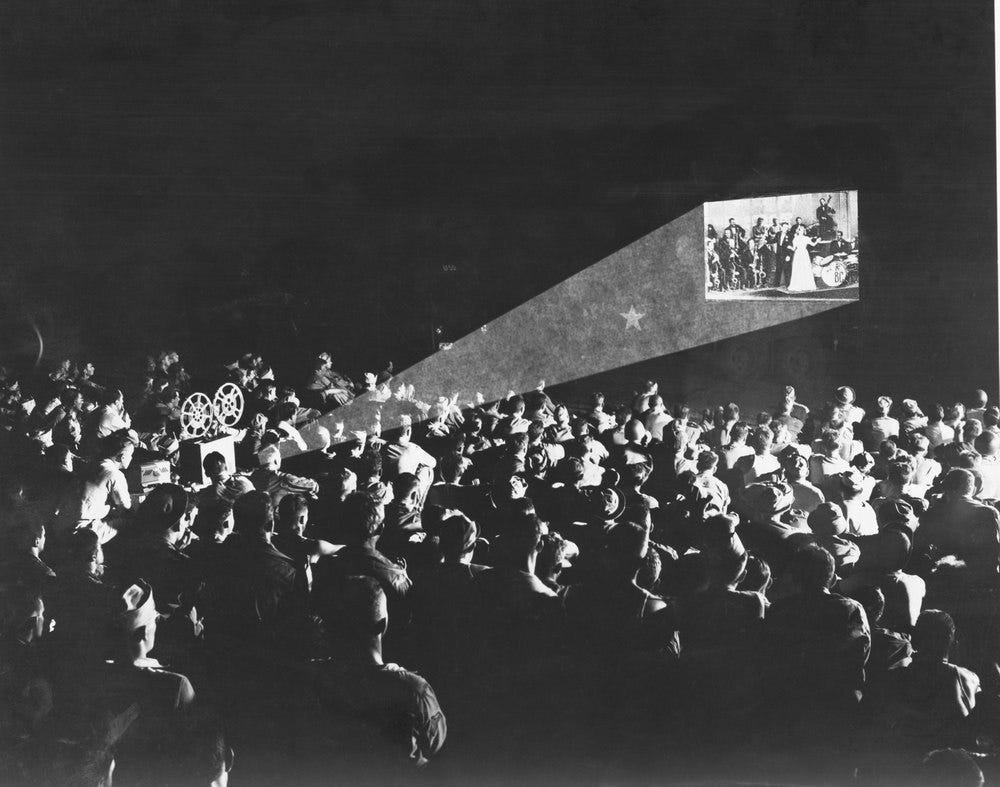

There’s a unique hush that falls over a darkened movie theater.

In the charged moments after the house lights dim but before the feature begins. Or at home, interrupting your doomscroll.

It is in this space that a very particular 150-second art form resides.

The modern movie trailer.

A horn blast, piano note or shriek of a siren. For the next two and a half minutes, the audience’s held captive by a “minor opus,”.

The movie trailer has traveled a long and improbable journey from a misnamed, post-film gimmick to what we know today. It is simultaneously a commercial, short film, and also propaganda.

All engineered to connect directly with our most primal desires.

We’re going to dissect its anatomy, its accidental history, and its psychological mechanisms to reveal the precise alchemy that transforms the trailer into a work of art.

History of the Hard Sell

The trailer’s evolution mirrors cinema itself. Constructed through innovation, commerce, and rebellion. Yet it truly began as an afterthought.

The first “trailer” debuted in November 1913. Not for a film, but a Broadway musical. Nils Granlund, the savvy ad exec for Marcus Loew’s theater chain, spliced together rehearsal footage from The Pleasure Seekers into a short promo reel.

It played after the main feature, literally trailing the movie.

Audiences, of course, left before it rolled but the name stuck. Granlund quickly shifted, applying his “new and unique stunt” to films themselves, creating some of the earliest slide promos for Charlie Chaplin comedies.

Age of Monopoly (1920s-1950s)

As cinema grew, so did the demand for standard marketing. In 1919, entrepreneur Herman Robbins founded the National Screen Service (NSS), which soon monopolized trailer production for nearly forty years.

He perfected the hard sell: bold, bombastic text and a commanding “voice of God” narration marching audiences through the plot.

The goal was nothing but clarity. Make sure audiences knew exactly what they were buying.

Trailers like this:

The Auteur Fights Back (1950s-1960s)

The NSS monopoly crumbled in the 50s, just as the “auteur theory” took hold. That shift spurred a new wave of filmmakers taking creative control. Control over everything. Including marketing.

Directors like Welles, Hitchcock, and Kubrick began cutting their own trailers, treating them as extensions of their vision.

Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) trailer broke the mold. He stayed off-screen, using only his voice to tease characters and mystery over plot.

Hitchcock went further with Psycho (1960), turning the trailer into a literal MTV Cribs-like six-minute tour of the Bates Motel, ending with that infamous shower reveal.

Blockbuster Boom (1970s-1990s)

If auteurs made trailers art, then the blockbuster era made them business.

Jaws (1975) was the turning point. its three-minute trailer laid out nearly the entire plot for TV audiences, turning the film into a national event.

This period also birthed the iconic narrator voice. Percy Rodriguez, then Don LaFontaine, whose legendary “In a world…” became Hollywood’s most famous opening line.

Digital Revolution (1990s-Present)

The internet permanently reshaped the trailer.

By the mid-’90s, studios were uploading clips online, and platforms like Apple Trailers and later YouTube turned the theater preview into a personal, shareable event.

One trailer became many.

Teasers, red-bands, countdowns, and even “trailers for trailers.” Each drop fed the hype cycle, with first-day view counts replacing box-office buzz as the new measure of success.

Deconstructing the 150-Second Symphony

A great modern trailer has to tell a story, set a tone, introduce characters, and spark excitement all under the two-and-a-half-minute limit set by the Motion Picture Association of America.

Even in under three minutes, most great trailers follow a classic three-act structure.

Act 1: Setup The first 30–40 seconds establish the world, the hero’s normal life, and the disruption that sets everything in motion. (The Matrix opens with Neo’s mundane world, then asks, “What is the Matrix?”)

Act 2: Confrontation Stakes rise. The conflict, antagonist, and “money shots” appear. Action, jokes, or spectacle that showcase the film’s scale.

Act 3: Climax Music swells, cuts quicken, emotion peaks. Usually ending on the title reveal, then a sharp “button” in the form of a final laugh, scream, or twist.

Art of Pacing

Pacing is the heartbeat of a trailer. Editors often build an audio spine first. Music, dialogue, and sound then cut visuals to its pulse. The goal is to create micro-stories: flashes of conflict or wonder that end just before payoff, keeping audiences hooked through unresolved tension.

Sonic Landscape

Sound is the trailer’s emotional engine. Music sets tone like The Social Network’s haunting choral “Creep” while effects like the InceptionBRAAM, rising whooshes, or sudden silences punctuate emotion. A single cut to black can hit harder than any explosion.

Voice of the Film

The booming narrator is extinct as was resurrected as dialogue which now carries most trailers. Editors remix lines from across the film into new exchanges that fit the trailer’s arc.

In the scroll-driven internet age, every sound acts as a pattern interrupt, built to stop you mid-scroll.

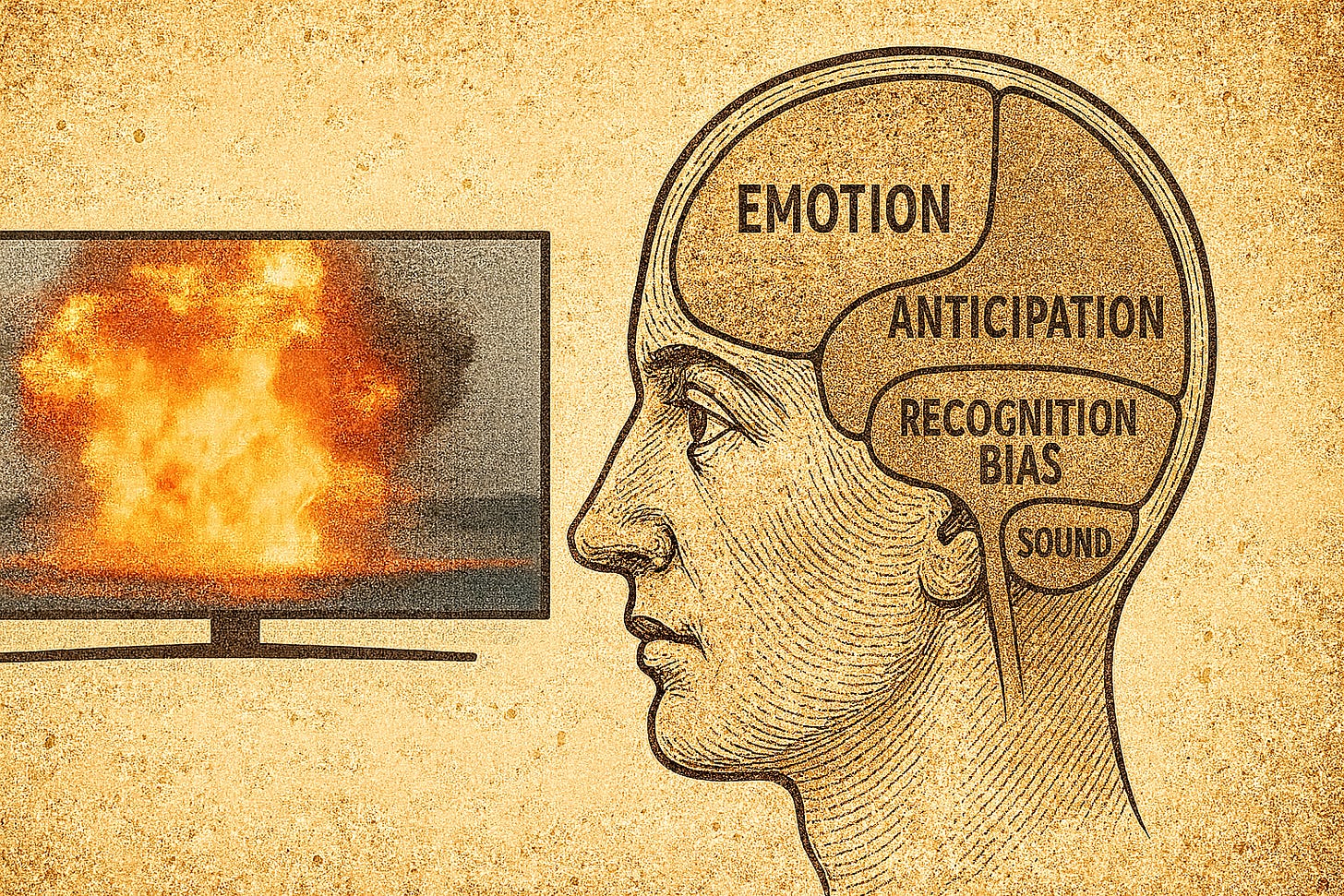

Psychology of the Sell

Trailer editors work to a script shaped by the film’s marketing strategy but the real craft begins in the chaos. Often handed hours of raw footage, they sift through it frame by frame, distilling an entire feature into roughly 2,880 carefully chosen images.

Behind that compression lies more than instinct. It’s a process grounded in psychology, rhythm, and data: the science of how to make two and a half minutes feel unforgettable.

Anticipation

Trailers thrive on tension and incompleteness. By showing fragments like a hero in peril or a romance unresolved they exploit our craving for closure. We imagine the missing pieces and feel compelled to see the film to complete the story.

Emotional Engineering

Every element; music, pacing and color targets emotion. The best trailers sync the film’s emotional promise to the audience’s mood, selling not a story, but a feeling they want to feel.

Cognitive Shortcuts

They lean on familiar biases: repetition breeds affection (mere exposure), small engagement leads to larger buy-in (foot-in-the-door), and star power substitutes for logic (peripheral persuasion).

Spoilers vs. Intrigue

Modern marketing favors clarity over curiosity. Execs and test audiences reward trailers that explain rather than entice, leading to spoiler-heavy cuts that trade mystery for metrics.

The Social Network Trailer (2010) - Art of the rebrand

When David Fincher’s film about the founding of Facebook was announced, it was widely met with skepticism and mockery.

Who would want to see a film about Facebook?

For months, it was billed as the grand collab between Fincher, generational director of Fight Club and Aaron Sorkin, one of Hollywood’s most celebrated screenwriters, known for his whip-smart dialogue in The West Wing and A Few Good Men.

Still, most people couldn’t see how a movie about the creation of a social network could be anything but dull.

But when the film’s first full trailer, created by the agency Mark Woollen & Associates, dropped on July 17, 2010, people were forced to eat their words.

It was marketing jujitsu that rebranded a “movie about Facebook” as a serious, weighty, and tragic drama.

Less a tech story than a Greek tragedy about ambition, betrayal, and loneliness.

The trailer was completely unconventional with its structure and use of music. Nearly 50 seconds pass before we even see the first actor, Jesse Eisenberg. Almost halfway through the trailer’s runtime.

Instead we see a mesmerizing, mosaic of the Facebook interface. Photo tags, status updates, friend requests. All grounding the film in a digital reality universally familiar to the audience.

Laid over this is the masterstroke: a haunting, ethereal choral cover of Radiohead’s “Creep,” performed by the Scala & Kolacny Brothers choir.

The choice of song is thematically perfect, reframing Mark Zuckerberg’s story not as one of tech-bro triumph, but as a deeply ironic tragedy of a social outcast who creates the world’s largest social network only to end up profoundly alone.

The trailer became a cultural event and widely hailed as one of the greatest ever made. It transformed a film once written off as a joke into a must-see awards contender.

Future of the first impression

The movie trailer currently stands at a crossroads, shaped by the fragmenting forces of our media landscape and the disruptive potential of new tech.

Its fundamental purpose remains unchanged, but the methods for achieving it are in a state of rapid evolution.

The theatrical trailer, while still important, is just one piece of a much, much larger and more complex puzzle.

A successful marketing campaign must now deploy a staggered, multi-format strategy, tailoring content to the specific demands of each platform.

A two-and-a-half-minute, widescreen trailer designed for a captive theatrical audience or a YouTube “event” release is fundamentally different from the short, vertically-oriented, and instantly-engaging video required to stop a user’s scroll on TikTok or Instagram Reels.

This new reality calls for agility. A blend of art, data, and intuition released in waves rather than single bursts.

Because if the trailer once lived only in the dark before a film, it now has to live everywhere. On screens, in feeds, and in our heads long after it fades to black.

If you liked reading this newsletter, don’t forget to give it a ❤️

Terrific article - so well written and presented. Who has the byline?

well done!