The Cut That Changed Everything. Screenlife: The Film Genre That Turned Our Screens Into The Scene

A genre born from webcams, refined in lockdown, and now the native language of digital storytelling.

Hi friends,

Another week, another step into the future of editing.

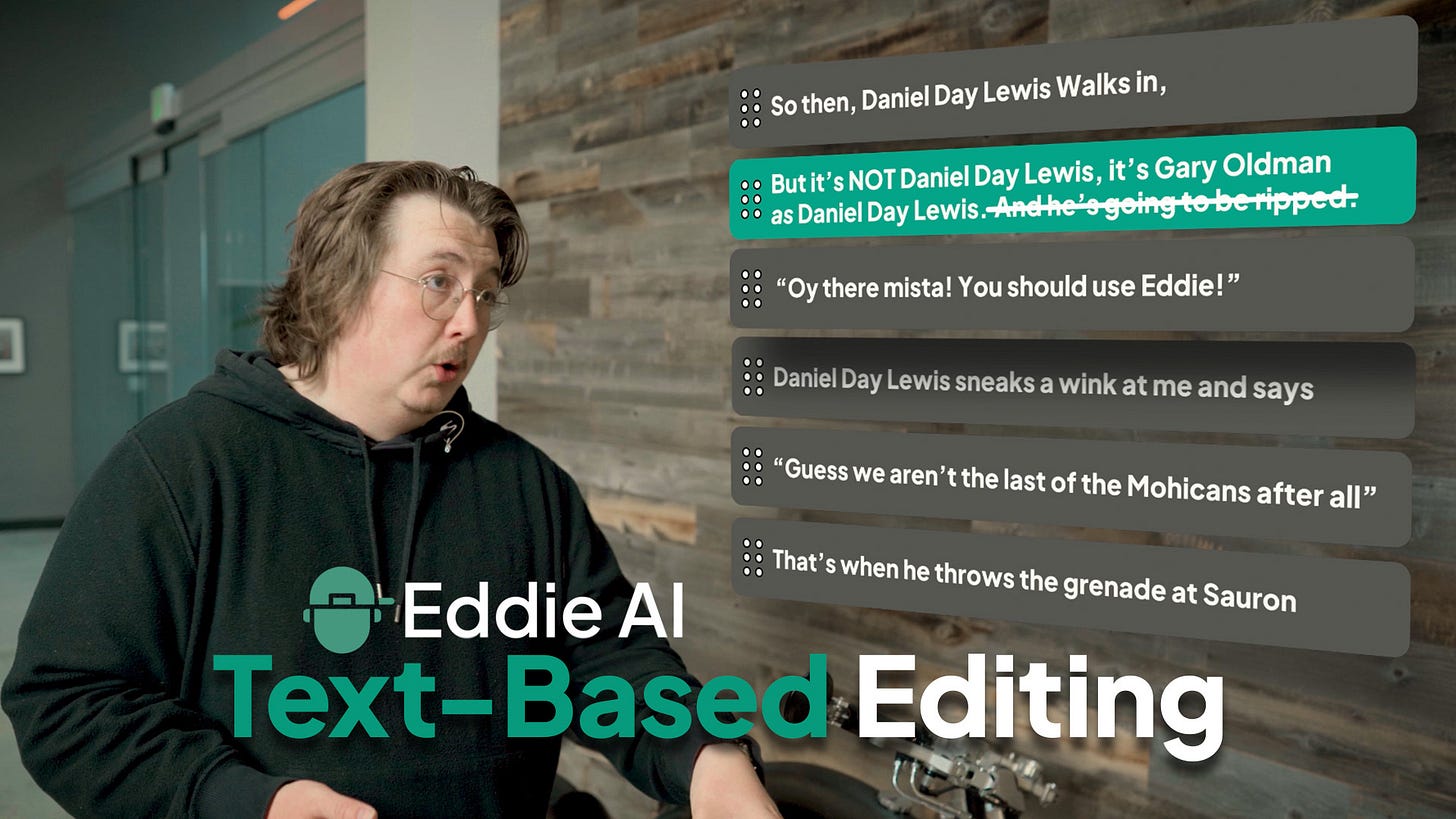

We just launched text-based editing inside Rough Cut mode—a brand new way to shape your story. This comes just a week after we dropped Scripted Mode. Our video marketing crew is busy. :)

If you’ve used Eddie before, you know Rough Cut is like having a tireless assistant who combs through hours of footage and assembles a solid first draft for you. Now, you can take that AI-generated string-out and refine it with the precision of a writer.

Want to cut a line? Just delete it.

Reorder a moment? Drag and drop.

Correct a name? Click, tap, tap.

All from a clean, intuitive script view.

🎬 The feature is live now in the latest Eddie Mac/PC version.

Now, onto this week’s deep dive. We’re exploring Screenlife, the genre where the screen is the stage. From FaceTime thrillers to browser-based mysteries, Screenlife took the voyeurism of found footage and rebooted it for the digital age. It’s low-budget, high-reward, and weirdly intimate, perfectly tailored for creators who live online (so… all of us).

Let’s get into it.

—Shamir

Screenlife

You’re in it right now. Reading this on a screen. Scrolling. Probably toggling between tabs (I, myself have 23 open), maybe glancing at the unread Slack message drawing your attention (It can wait, keep reading).

Anyway, that’s the idea.

Screenlife is the genre where the screen is the scene. And the set too. No cameras but the tiny dot at the top of your laptop. Or not even a camera at all. Sometimes, it’s literally the screen. Recording.. And a faceless cursor with the digital bread crumbs of someone’s story unfolding in real time.

Think: FaceTime calls, Instagram DMs, Google searches, TikTok drafts. The world Screenlife lives in.

The precursor to Screenlife was the found footage genre.

Films like The Blair Witch Project (1999) and Paranormal Activity (2007) broke traditional narrative form by pretending footage had been “discovered” rather than staged, creating a raw, immersive experience.

Found footage made the viewer complicit, like they were watching something private and real. Screenlife took that same voyeurism and updated it for the now.

Or at least the 2010s.

Early pre-Screenlife experiments include:

The Collingswood Story (2002) Low-budget indie horror film told through webcam conversations

Megan Is Missing (2011) Controversial pseudo-found-footage thriller using video chats and text messages

Screenlife truly crystallized as a genre in the mid- 2010s, right when everyone started living online.

It was an easy sell across the board.

You had relatable premises and themes; social media, missing person, catfishers and you had style of filming that didn’t need a set. And barely needed a crew in comparison to larger productions.

Just a screenplay (and maybe not even that), screen recording software, and an editor who’s online-literate.

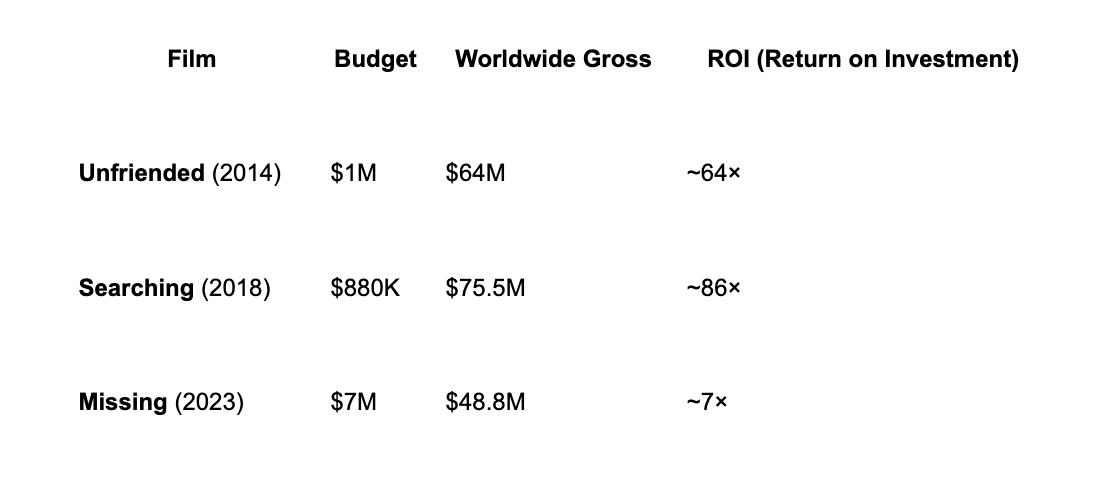

In an era obsessed with ROI, screenlife emerged as a low-risk, high-yield format: viral potential with micro-budget spend.

I mean just look at the math:

It’s a genre that can sell with no stars, just like Horror doesn’t.

Screen to Stage

The year: 2014. Unfriended drops. A horror film told entirely through a MacBook.

One continuous screen recording of a teen’s desktop. Skype calls, Spotify queues, and passive-aggressive group chats as supernatural forces tear the digital façade apart.

Timur Bekmambetov, the Kazakh filmmaker behind Wanted, produced it and is now regarded as the pioneer / coiner of the term Screenlife.

Then came Searching (2018), starring John Cho. A missing daughter. Frantic father. And a trail of browser history, livestreams, emails, and forgotten login screens. While Unfriended weaponized the interface for fear, Searching turned it into a medium for emotional unraveling.

Each click carried weight. Each pause in typing revealed more than dialogue ever could. It proved that Screenlife could be more than a genre gimmick.

By now, Screenlife had explored horror and thriller. But what about comedy?

Enter Spree (2020). Joe Keery (Stranger Things) plays a rideshare driver with no followers and big influencer dreams. His plan is to livestream a killing spree (I probably should’ve mentioned it’s a dark comedy), one five-star trip at a time.

Taxi Driver but for TikTok.

It’s also exec produced by Drake.

But what makes Spree essential isn’t just the plot. It’s the editing. The entire film plays out in livestream overlays, social app notifications, and frenetic comment threads.

Director Eugene Kotlyarenko employed a hyper-realistic formalist approach which meant the viewing experience of the film felt like a literal live stream.

Not a simulated one.

Screen is the stage.

Why It Doesn’t Work for Everyone

Not everyone’s cheering.

It’s “gimmickry”. “digital voyeurism masquerading as cinema”. Too much clicking, not enough camera. They argue that turning desktops into drama sacrifices the richness of visual storytelling for an interface.

The edit becomes literal, maybe even sometimes lazy.

And if the drama hinges on when a notification pops up or a message goes unsent, what happens when the novelty wears off?

Others point to the form’s claustrophobia. Some Screenlife films are worse than a bore to get through. They’re a chore. Meaning it’s actual hard work constantly watching an actual screen for 90 minutes.

Even exhausting, like watching someone else multitask.

It can really be a tough sell for anyone craving escapism because it doesn’t let you forget you’re staring at the same digital world you just tried to log off from.

Like, why watch a screen about a screen when I already spend all day glued to one?

Well, sometimes the most honest mirror we have is the one already lit up in our hands and Screenlife isn’t here to help us escape reality, it’s here to show remind us about the one we’re already living,

A Style in Vogue

Model Bella Hadid poses in the first large scale FaceTime fashion campaign. 2020.

Lockdown 2020.

All forced inside, physically and creatively.

With sets shut down and teams scattered, artists had to reimagine production within the four walls of their homes.

The Screenlife “style” infected the fashion world as FacetTime photoshoots even at the scale of a Vogue feature were shot via FaceTime.

Bella Hadid fronted Jacquemus’s Spring 2020 campaign from an empty room, styled and photographed remotely, using nothing but FaceTime.

It was considered the first big FaceTime campaign, birthing a wave of Zoom shoots that became a new normal.

Photographer Elizaveta Porodina shot indie movie darling, Chloë Sevigny entirely through a screen for The Cut.

Italian photographer Alessio Albi directed actress Alice Pagani remotely from his apartment across continents via Zoom.

If the COVID-era FaceTime fashion shoots proved anything, it was something radical.

Compelling, pro-grade storytelling could happen entirely within the confines of a screen.

A revelation for fashion and a confirmation for filmmakers.

For aspiring creators: if you have a screen, you have a set. You don’t need a budget, you need a browser. And if you know how to choreograph tabs, pings, and pauses, you’re halfway to a story.

Here’s how to do it.

Step 1: Record the Screen

Use:

CleanShot X (Mac) great for framing and annotating.

OBS Studio (Mac/PC) free, flexible, and stream-ready.

ScreenFlow or Camtasia for power users who want editing baked in.

Even Quicktime screen recording can do the job

Step 2: Animate Interface

Use:

After Effects: build window choreography, time out notifications, fake typing bubbles.

Keynote/PowerPoint (yes, really) : surprisingly useful for simple UI mockups.

Figma or Canva : design fake DMs, tweets, apps.

Or skip the fakery altogether. Just write the messages and trigger notifications live. Of course, that means you’ll actually need friends.

Or at least a burner phone and some emotional range.

Step 3: Voice It or Fake It

Go full narrative with VO like Searching, or lean into livestream-style like Spree.

Use:

Adobe Audition, Descript, or even iPhone Voice Memos.

Want to simulate a FaceTime convo? Record both ends separately, then sync in post.

Bonus Tools & Templates

CapCut, VN Video Editor, and Runway now have screenlife-style overlays and templates. Great for TikTok edits.

Try Typewriter Simulator or Text Message Generator online to fake real-time convos.

Need fake Slack threads or inboxes? Notion, Super.so, and a screenshot will do.

Hi, Still there?

Well, if you’ve made it this far you now know how Screenlife flipped the script: turning limitation into language, bandwidth into budget, and the ordinary chaos of our desktops into a cinematic playground.

But where does it go from here?

Will we tell entire epics in browser tabs? Will AI-generated interfaces let us simulate fake digital lives faster than we can live our own?

What screens are we limited to? Smart fridges, fitness trackers, car dashboard?

Or maybe we hit saturation and the genre will evolve into something else.

Maybe we need the silence of a wide shot again.

But until then, Screenlife sits at a curious crossroads, equal parts cinematic experiment and cultural mirror.

A genre born from constraints now asks a limitless question:

If our whole lives are on-screen, how far can the edit go?

Your move.