The Lost City of NLEs: How Lucasfilm Built and Buried EditDroid

From George Lucas’s editing lab to Avid’s rise, a dive into the lost machine that shaped modern post.

Hi everyone—

Hope you’re having a wonderful week.

We extended our 1,000 DOCS grant program and announced some of the recipients. If you’re working on an indie documentary film, submit your project here.

We also added support for dozens of new languages to Eddie AI last week. You can now craft edits from interviews in Spanish, German, French, English and many more languages.

And there’s a few more updates we are hard at work on. Stay tuned in the next few weeks. As always, don’t hesitate to reach out with any comments, questions and suggestions.

Let’s dive in to today’s newsletter.

—Shamir

Avid Media Composer was the first nonlinear editing (NLE) system to conquer Hollywood. But before Avid, there was Lucasfilm’s EditDroid.

Born in the early 1980s inside Lucasfilm’s Computer Division, EditDroid promised instant random access, a graphical timeline, and the ability to cut without ever touching reels or tape.

And before that? The CMX 600, built in 1971. Often credited as the very first NLE, a refrigerator-sized, tape-based beast that was more proof-of-concept than practical tool.

But that’s a rabbit hole for another day. Because this isn’t the story of CMX.

It’s the story of Lucasfilm’s lost droid, a bold $40 million bet that for a very brief moment, looked it had brought the future of editing from a galaxy far, far away.

George Lucas, the Ideas Man

George Lucas was always more of an ideas guy.

But from his USC days to the Star Wars era, Lucas never stopped thinking like an editor, constantly rearranging sound and visuals, frustrated by what he called the “19th-century process” of physically cutting and taping celluloid.

He wanted something faster, freer, more creative. And he was willing to put serious money behind it.

In 1979, Lucas formed Lucasfilm’s Computer Division to explore these possibilities, investing $40 million into EditDroid and its sibling SoundDroid, betting big that post-production would become the next frontier of film technology.

Ed Catmull, a computer scientist from NYIT (and later co-founder of Pixar), was recruited to run it. The division would birth THX sound, digital imaging research, and eventually Pixar itself.

Among their projects: a nonlinear editing system.

Enter EditDroid

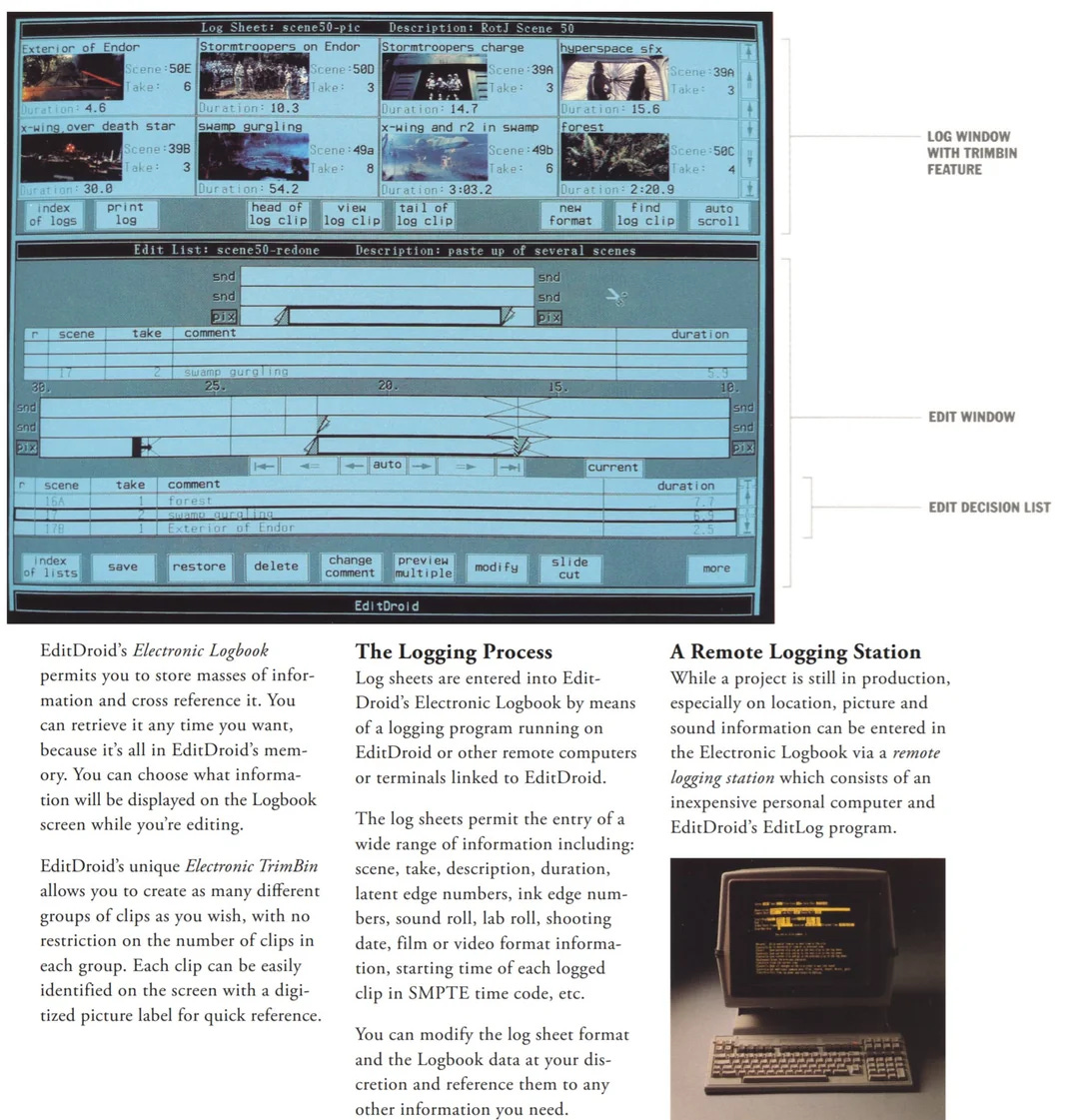

Catmull brought in Ralph Guggenheim to oversee the NLE project. They imagined a workflow where film could be scanned digitally, edited with random access, then re-printed back to film. To make it feasible in the early ’80s, they turned to videodiscs.

Through years of trial and error, the team built a system combining:

Laserdisc storage. Each disc held ~30 minutes per side.

Multiple synced players. Chained together for longer projects.

A Sun workstation. Providing a graphical interface. Bins, timelines, in/out points.

A custom touchpad. Including a KEM-style jog knob for tactile control.

By 1984, the machine was ready. Lucasfilm and manufacturer Convergence Corporation unveiled the EditDroid at the NAB convention, the same year Apple launched the Macintosh.

It looked futuristic and it worked. Well, at least in controlled demos.

For the first time, editors could glimpse a system of the future that bore real resemblance to the digital editing we know today.

Why EditDroid Was Groundbreaking

It was a preview of the entire nonlinear era.

For editors chained to tape decks and film reels, the features sounded almost miraculous:

Random access. No more scrubbing tape. Jump instantly to any frame.

Timeline grammar. The GUI introduced bins, preview windows, and a timeline. The same grammar we still use.

Collaboration. Multiple players made it possible to scale up to bigger projects.

Lucasfilm halo. The association with George Lucas and Star Wars lent instant credibility and drew attention to nonlinear editing as a serious future.

But to really understand why EditDroid mattered, you have to feel the pain of what came before.

1983:

You’re in the edit bay. The director leans over your shoulder: “Let’s try the other take.”

You sigh, reach for the catalog, find the code. It says the reel is in Box 42, top shelf. You drag over a ladder, climb up, wrestle the box down.

Pop it open, peel off the tape, pull out a little roll of film. Onto the reel it goes, threaded into the Moviola.

The projector whirs, image flickers. The director squints: “Oh… not that one.”

Ten minutes gone. For one take. Multiply that by a hundred “what ifs” and you start to see why Lucas called it a 19th-century process.

2025:

You type three letters into a search bar. All the takes appear instantly. One click, it’s on your timeline. Another click, it’s gone.

That’s the gap EditDroid was trying to close.

And for a short window in the mid-’80s, it really looked like it might happen.

The Odd One Out

EditDroid came from the same family that gave us THX, Pixar, ILM, Lucas’s Computer Division. All birthed from a pursuit of a future of film technology that Hollywood wouldn’t pay for it.

THX thrived as a gold standard for cinema sound. Pixar spun out and rewrote the history of animation. ILM became the industry’s effects powerhouse.

EditDroid was born of that same energy and same ambition. Yet its path would turn out very differently.

So…why did EditDroid die?

Short answer: it didn’t work.

Longer answer:

Beyond the technically flaws, EditDroid faced a credibility gap.

At NAB in 1984, Lucasfilm wowed crowds with never-before-seen Return of the Jedi footage running on EditDroid. But the irony was impossible to miss: George Lucas hadn’t actually cut any of Jedi on it.

If he didn’t trust his own invention to handle his film, why should anyone else?

The Droid did find believers though.

Oliver Stone used it on The Doors, wrangling a dozen cameras of concert footage, and wanted it again for JFK before a rental dispute pushed him away.

Others recalled units plagued by breakdowns, while later redesigns proved themselves on TV shows like Law & Order.

Lucas himself finally committed with The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles.

The Issues

Laserdisc limits. 30 minutes per side meant towers of discs for features.

Revision bottlenecks. Any change required pressing new discs. Painfully slow.

Fragility. Discs scratched; syncing multiple players often broke down.

High cost. Systems were expensive, often leased rather than bought.

Industry skepticism. Editors were wary. The system didn’t feel production-ready.

Marc Wielage, legendary Hollywood colourist who used an EditDroid in the 80s, later recalled on Reduser.net:

“It never worked very well. They had a lot of technical problems with it, and our company refused to pay Lucasfilm for it until it worked. Around 1987, our GM called and said, ‘We’re moving other editing systems in, come get this.’ Lucasfilm basically said, ‘We’ve written it off, keep it.’ They hauled it to the dump. I managed to save a couple of the demo discs.”

Another engineer, forum user Paul Fr, worked on a second-generation redesign:

“We rebuilt it from scratch, using the same concepts. That version was reliable, and it supported Law & Order and Oliver Stone projects without a hitch. But by then, Avid had shown up at NAB. I knew it was over for us.”

In the end, only 30 EditDroids ever saw the light of day and by the early ’90s, Lucasfilm exited the hardware business entirely.

The lost city had officially sunk.

Or had it?

From Ashes to Avid

In 1993, EditDroid found new life when Lucasfilm sold it, along with its sibling SoundDroid to Avid Technology., then emerging with its own computer-based editors.

Whether patents or simply know-how, the DNA carried forward.

By the end of the decade, Avid was cutting blockbuster films, while consumer systems like Premiere and Final Cut put editing on home computers.

As Wielage noted, Avid may not have directly reused all of EditDroid’s designs, but concepts like the KEM-style jog controller and the GUI timeline found new life.

After the Metropolis, the Machine

That was the dream: to get editors out of the weeds of film spools and trim bins, and back into storytelling. The irony is that editors today voice the same frustration, just in a digital key.

Logging, sorting, pulling selects are all time eaters. What they really want is the same thing Lucas wanted for his editors.

To edit, and not manage media.

AI workflows are starting to close that gap. They promise to do for the logging and assembly phase what EditDroid once promised for reels and tape.

EditDroid was never mass-adopted, but it endures as the buried city beneath modern-post. Avid rose as the thriving metropolis but together they laid the foundation for the nonlinear editing world we live in today.

I then turned my attention to EditDroid/SoundDroid. The situation here was a bit murkier as I reflected on what I knew of the origin story.

George’s vision was that Lucasfilm would develop a proprietary system for editing film, so he brought Ed Catmull over from the New York Institute of Technology, where they were doing groundbreaking work in computer graphics. Catmull recruited Ralph Guggenheim, and under Ralph’s direction, Lucasfilm created EditDroid.

EditDroid was a non-linear editing system based on SUN hardware coupled with a Pioneer laserdisc system. This system was light years ahead of the old way, where an editor had to go poking around in physical bins to look for the piece of celluloid they needed to edit into a scene.ix With EditDroid, an editor could access all footage instantaneously. All that was required was for the raw footage to be sent to L.A. and transferred to laser discs, which took a week or two.

When it was invented in 1984, this seemed revolutionary—and it was, for about a nanosecond. In 1988, I attended the National Association for Broadcasters (NAB) convention in Las Vegas. The NAB features the latest and greatest technological innovations, and that year, this new hotshot company was there, showing its wares: Avid Technology. I watched the demo with a mix of fascination and chagrin. The difference between our Droid system and Avid’s was that theirs ran on computer hard discs, not laser discs. This system cut out the middleman. The transfer could be done in-house and fast. This was so much easier and much more elegant.

I now had a decision to make. On my ride back, I went over the scenario. The EditDroid system had two advantages: It bore the George Lucas trademark, and the interface was designed by actual film editors, not computer techs, so it had the “feel” of a Steenbeck, traditional film-editing equipment. The downside, however, was there were hardly any takers.

Given what I’d seen at NAB, I concluded that EditDroid was a losing proposition, something I was sure Lucas would not want to hear. Then, I had a brainstorm. I saw how we might salvage EditDroid and create a win-win for everyone involved.

When I returned, I went to Norby. “These Avid guys are going to eat our shorts,” I told him. “This is a much, much more advanced technology, and it will work really well.” I paused and waited for this to sink in before I launched into the rest. “So now, we need to go to Avid and put together a deal with them for a co-venture.”

I saw astonishment register on his face, followed by skepticism.

“In return for a share of the profits, we would permit them to use the George Lucas brand, the EditDroid name,” I continued. “Their technology is great, but Avid is a new player in the market. Lucas’s name would give them instant street cred. In addition, we would also actively encourage all the great editors we’ve worked with, people like Walter Murch,x to provide testimonials, telling other editors how great the system is. This would be a win for everybody.”

This could work; I could feel it.

“Absolutely not,” was Norby’s immediate reply.

I went back to my office shaking my head, knowing this decision was going to come back to bite us. Sure enough, it did. Over the next few months, we watched Avid become accepted as the industry standard while EditDroid continued to lose money. It had become blindingly obvious that EditDroid was going nowhere and that I needed to shut it down. So, I did. A week later, however, I discovered that it was back up. The reason, I learned, was that George—with whom I never got to speak—had decided that EditDroid’s position in the marketplace was very important to him, and its failure was not something he could accept.

I decided to try again. I went back to Norby. “Let’s get back to Avid and put a deal together with them. If we use their tech, we can save the brand. It’s the only way to make this work.”

Again, he said, “Absolutely not.”

I was angry now and terribly frustrated. With regrets expressed to the employees, I closed EditDroid down again.

A week later, I discovered they’d all been hired back. Could it be that Norby wanted me to fail? Was he so desperate to do so that he was willing to allow EditDroid to continue to lose money?

Some links people have shared with me:

A book about the history of EditDroid:

https://www.droidmaker.com/

And a documentary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z99wO2utddo