The Other Coppola: From Eleanor’s Apocalypse to the Ghost of Megalopolis

Chaos, creation, and the cost of being a Coppola.

Hi everyone —

Happy Thursday! TBH it feels like Friday as it’s been a busier week than usual.

Something anew is launching next week. ;) New launch means new video. :)

And we partnered on a novel film festival, Playback, that happened this past week in Chinatown, San Francisco. Playback celebrates video storytelling meets tech, specifically tech product launch videos that skew narrative.

What I saw in Playback is it is the start of the realization of the importance of video storytelling. Not just in tech products. But for everything.

Stories entertain, engage, and inform. They stir and shake and sometimes jolt us into action. Why should it only be reserved for feature films?

And the bar for storytelling will only get higher. In a world of video everywhere, the value of great storytelling will rise.

We are here for this. We are here to do our part to make it rise.

Thanks for joining us on this journey. As always, don’t hesitate to reply to this email.

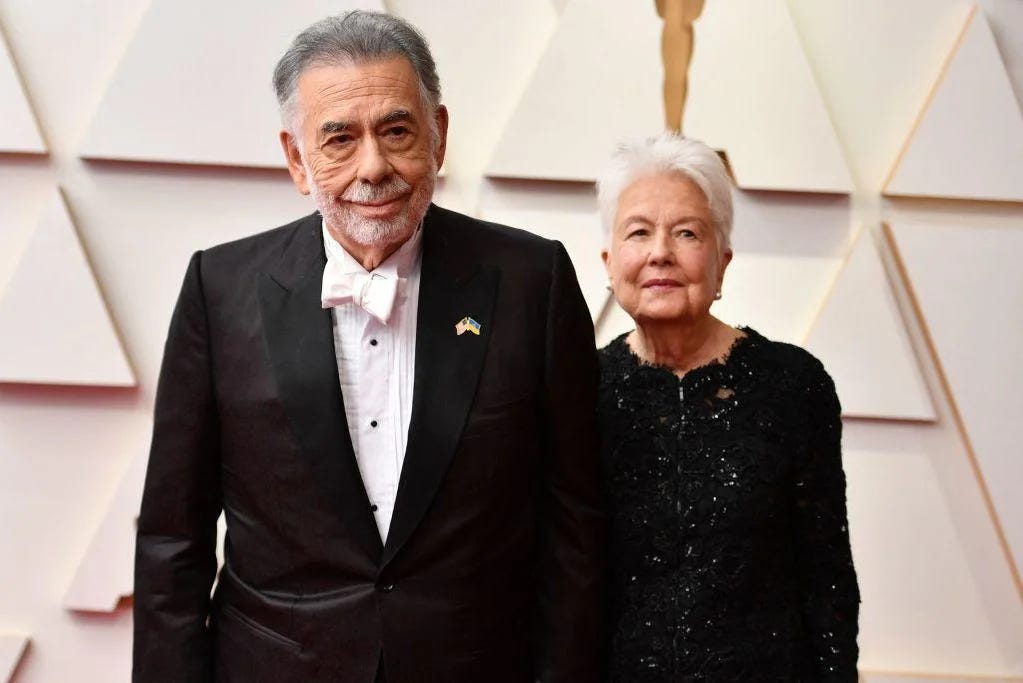

And speaking of great storytelling and storytellers, today’s newsletter is about Francis Ford Coppola and his documentarian wife Eleanor Coppola (who also lived in the SF Bay Area).

Enjoy!

—Shamir

CEO & Co-founder of Eddie AI

At this year’s Venice Film Festival, a ghost walked into the room when the documentary about Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, Megadoc premiered.

Not Francis Ford Coppola. Not even Mike Figgis, who directed it.

The ghost belonged to Eleanor Coppola, the artist, diarist, reluctant documentarian and Francis’ late wife, whose lens first taught us how to see Francis’s creative unraveling.

Figgis’s Megadoc arrives with deliberate echoes of Eleanor’s Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991), the legendary behind-the-scenes chronicle of Apocalypse Now.

But where Eleanor returned from the jungle with a mythic text about genius forged in chaos, Megadoc offers something different: a spectacle of the same chaos, this time ending in failure.

Together they trace the cost of creation. Myth on one side, ruin on the other.

Artist as Witness

Before she was known as Francis’s wife, Eleanor Neil was an artist.

She studied design at UCLA, immersed herself in the Bay Area’s conceptual art scene, and exhibited performance pieces blurring the lines between process and life.

In 1962, fresh out of school, she took a job as an assistant art director on a scrappy black-and-white horror film called Dementia 13. The director was none other than a 24-year-old named Francis Ford Coppola.

They married two years later.

By the mid-1970s, Eleanor had a front row seat to the rise of New Hollywood, but when Francis set out to make Apocalypse Now, a project that swallowed years, money, and sanity, she decided not to stay a passenger.

She picked up her 16mm camera, at first, simply to document family life in the Philippines and gather behind-the-scenes material, United Artists could use for promotion.

But the footage quickly became something else.

Instead of marketing fluff, she shot fever-dream fragments of typhoon-wrecked sets, breakdowns, and whispered confessions.

She also kept meticulous private journals. Tools of her art practice: document everything, interrogate the frame, blur the line between performance and reality, suddenly became the only way to survive the madness around her.

Notes in the Jungle

Her book Notes on the Making of “Apocalypse Now” (1979) is part diary, part existential confession.

In it, she wrote of her husband’s spiraling ambition: “That fine discrimination that draws the line between what is visionary and what is madness seems missing.”

A decade later, that diary and footage became Hearts of Darkness.

Time transformed the raw trauma of production into a historical reckoning. What could have been dismissed as promotional filler became instead a mythic account of artistic struggle, curated with the distance of hindsight.

Every film set courts crisis, but what happened on Apocalypse staggers belief:

Typhoons leveling million-dollar sets

Martin Sheen suffering a near-fatal heart attack

Marlon Brando arriving overweight and unprepared

Dennis Hopper lost in a drug haze

Philippine helicopters recalled mid-scene to fight real rebels

“Crisis” doesn’t quite cut it.

The Cannes Cut Controversy

Apocalypse Now limped into Cannes in 1979 much the way it was made.

Through chaos and brinkmanship. Festival director Gilles Jacob chased Coppola into the editing bay, finding him buried under miles of footage, insisting the film couldn’t possibly be ready.

Jacob refused to take no for an answer.

He offered to screen it unfinished, to waive rules barring past winners, even to bankroll Coppola’s Cannes stay on a yacht. Coppola agreed, but Jacob lived in fear he’d pull the film at the last minute.

The Croisette got Apocalypse Now (A Work in Progress): no credits and not even picture-locked. Reviews were split, especially on the ending, but the spectacle was undeniable.

The real drama came in the jury room. President Françoise Sagan favored Volker Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum for the Palme d’Or. But Cannes brass pushed back as Apocalypse had already set the festival ablaze with press, and it was “in the best interests of Cannes” for Coppola to win.

The compromise: a tie. Coppola left grumbling he’d only won “half a Palme.”

But half was enough.

Victory, no matter how messy, transformed years of disaster into legend. As Roger Ebert later wrote of Eleanor Coppola’s Hearts of Darkness, the film stripped Francis bare yet revealed him as a brave, almost fanatical artist.

Cannes had helped write the myth, and Eleanor’s camera ensured it would never fade.

The Other, Other Coppola and the Forty-Year Echo

Enter Megalopolis.

The $120m passion project.

Conceived in the late 70s, rewritten and rewritten and rewritten again. Finally self-financed in 2021 with funds raised from the sale of his vineyard, it was Francis Ford Coppola’s last great gamble.

Like Apocalypse Now, it was ruinous in scale. But the man taking the risk was no longer the same.

Coppola was nearing 82 years old, worth nearly half a billion dollars, and far, far removed from the scrappy filmmaker who once staked his house on a war film in the jungle.

Many critics argue he hasn’t made a clear classic since Apocalypse Now and Megalopolis is unlikely to change that. It’s almost as if part of him never returned from the Pagsanjan River in ‘79.

So if Eleanor was the first “other Coppola”, the one in his shadow who chronicled the king, Megadoc offers a portrait of the second: Francis himself, now an elder statesman chasing a vision of a bygone era.

And what Figgis’s camera finds is not triumph, but turbulence.

Mass Exodus. In December 2022, midway through the Atlanta shoot, Coppola supposedly dismissed his entire in-house VFX team. About thirty people fired instantly. Two major department heads followed: production designer Beth Mickle (The Suicide Squad, Guardians 3) and supervising art director David Scott. At issue was Coppola’s unorthodox use of a massive LED volume stage.

On-Set Confusion. Reports described Coppola vanishing into his Airstream while crews waited for direction. Improvisation was starting to look like indecision. “He’s a brilliant man,” one insider said. “But does he have the ability to pull this together?” Another: “Absolute madness.”

Pushback. Coppola denied anyone was “fired,” framing the departures as planned. Lead actor Adam Driver echoed him: “All good here! … This set is far from chaotic.”

The Actors. No Brando-level implosions this time. Stars like Driver, Aubrey Plaza, and Nathalie Emmanuel kept clear of drama, though Shia LaBeouf’s intensity sparked on-set clashes, moments Megadoc reportedly preserves.

The observer was different this time. Not Eleanor Coppola, embedded and bleeding into her diary, but Mike Figgis, a peer with a sympathetic lens.

Megalopolis: An Apocalypse Without a “Now”

The film premiered at Cannes in May 2024 just as Apocalypse had nearly fifty years earlier.

But this time Coppola faced a wave of scathing reviews, and his passion project was set to drift in limbo without a U.S. distributor for two and a half months.

Let that marinate a second.

A $120 million epic, directed by one of cinema’s all-time greats, his passion project of nearly fifty years, his first film in over a decade, starring Adam Driver, unveiled in competition at the biggest festival in the world and still…. no one wanted to touch it.

Usually, films of this scale secure distribution before Cannes.

At worst, they’re snapped up by the festival’s end. So for Megalopolis to languish in purgatory that long was something completely unheard of.

Price of Admission

Time will tell where Megalopolis lands in the Coppola canon.

But Megadoc, opening in limited U.S. theaters on September 19, likely won’t redeem the film so much as it will probe deeper into the dark interior of a mind still capable of bending art and culture to its will.

Francis Ford Coppola has spent his entire career proving that moderation and normality don’t make cinema history. Extremity does. Hubris does. These are prices of admission.

Eleanor understood that. With her diary and camera, capturing not just the making of a masterpiece but the cost of becoming a cinema great. She wrote the first draft of the myth.

Figgis, decades later, gives us the second.

After Hearts of Darkness cemented Eleanor as the unseen chronicler of Francis’s legend, Eleanor Coppola claimed her own space as a filmmaker. In her seventies she turned to feature directing. Paris Can Wait (2016), a light, observational road movie, was her first narrative feature; Love Is Love Is Love (2020) followed, a gentle triptych about intimacy and aging.

In hindsight, Eleanor’s career after Hearts of Darkness reads like a quiet counterpoint to Francis’s late-life gamble.

Where he kept doubling down on extremity, she embraced simplicity.

We may never see another filmmaker like Francis. But thanks to Eleanor, we can still read the diary of what it truly takes to gamble everything for art.

Thanks for reading. Let us know what you think in the comments or by replying. And share this newsletter with friends.