The Third Safdie: Ronald Bronstein and the Art of Editing Without Assembly Cuts

A deep dive into the editor who turns footage into warfare, scripts into tyranny, and Marty Supreme into a single sustained panic attack.

Hi everyone —

Hope you’re having a wonderful holiday break.

If you’re looking for a quick reprieve from the intensity of extended family members or thinking about why you had that fourth helping last night, I hope today’s Rough Cut newsletter provides that for you. :)

Enjoy!

Shamir

CEO & Co-founder, Eddie AI

Wherever you’ve been in the past few weeks, you’ve probably seen it.

Timothée Chalamet appearing on Good Morning America flanked by bodyguards with giant orange ping-pong balls for heads. Or the massive orange blimp floating over LA with “MARTY SUPREME” emblazoned across it.

Or The Statue of Liberty projection-mapped in hard-core orange.

Or the 18-minute fake Zoom call where he pitched A24 executives on painting the Eiffel Tower orange.

Or his appearance in a UK drill rapper’s music video for EsDeeKid’s “4 Raws” remix, debunking rumors he was the masked artist while somehow generating more mystery.

Timothée Chalamet’s press run for Marty Supreme has been as relentless and chaotic as the film itself. It opened nationwide on Christmas Day and has been heralded as a kinetic epic and a dark horse for the Oscars.

But it also marks something bigger: the official end of the Safdie Brothers as a directing duo.

Josh and Benny Safdie built their reputation as a directing duo over more than a decade through gritty New York stories shot with documentary immediacy.

Heaven Knows What (2014), Good Time (2017), and Uncut Gems (2019) established them as masters of sustained anxiety but it was Uncut Gems, starring Adam Sandler as a jewelry district hustler which became their breakout.

But last year, they split.

The result: two solo debuts. Josh directed Marty Supreme. Benny directed The Smashing Machine with Dwayne Johnson.

And when directing duos with a singular style split up, it usually begs the question: who was actually driving the style?

The Coen Brothers proved this. Ethan’s solo work (Drive Away Dolls, Honey Don’t) skews zany and absurd, which explains Burn After Reading and The Big Lebowski. Joel’s (The Tragedy of Macbeth) is austere and serious which explains No Country for Old Men.

The Safdies were known for anxiety. Chaos. Speed.

So which brother was driving that?

Well, Josh made Marty Supreme, and it’s a manic and propulsive screwball drama. Benny made The Smashing Machine without him, and it’s a somber character study..

Maybe Josh was the driving force all along.

But there’s one common denominator. Their longtime producer, writer, and editor worked on Marty Supreme but not The Smashing Machine.

So perhaps it’s the third brother. A brother not by blood, but by collaboration.

Ronald Bronstein.

A Safdie primary collaborator since 2008, he co-wrote and edited both Good Time and Uncut Gems, and played a supporting role in Daddy Longlegs. On Marty, Bronstein co-wrote the script with Josh and served as producer.

But perhaps most importantly, he was also the co-editor.

In recent interviews with the One Take podcast and Filmmaker magazine, Bronstein opened up about his editing philosophy: a process that rejects industry standards and treats the cutting room as a medieval battlefield.

Here’s how he works.

The Third Safdie

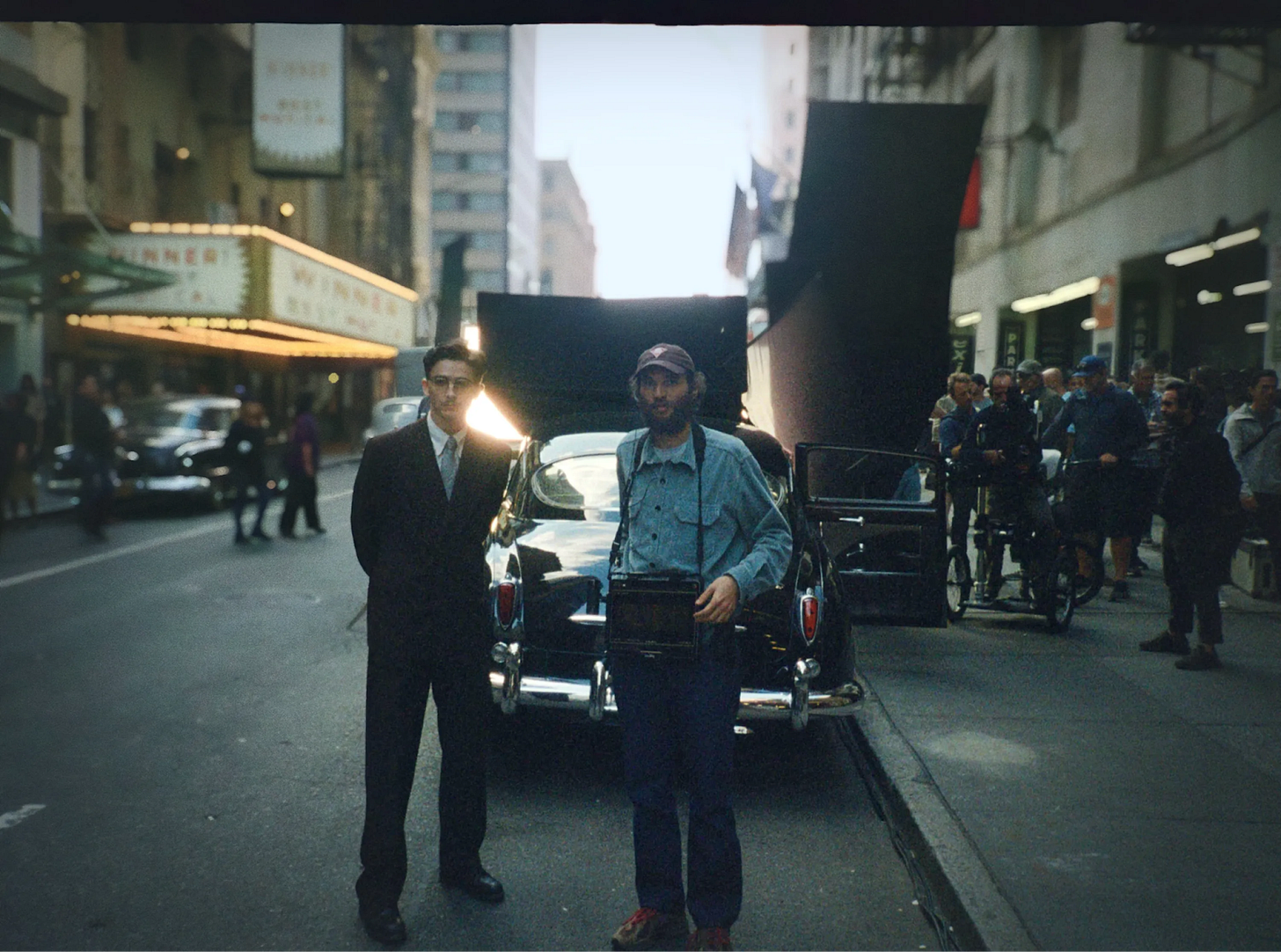

Their story begins at SXSW 2007, where Ronald Bronstein premiered his debut feature Frownland. The same festival where Josh Safdie’s short We’re Going to the Zoo played.

Bronstein watched it and felt his stomach drop.

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God, there’s somebody also vying for the same kind of immediacy. It was like my feet were made of lead; this guy was like a helium balloon.”

Back in New York, Josh introduced himself and convinced Bronstein to act in his next project, playing a character based on Bronstein’s own father. Bronstein ended up co-writing and editing what became Daddy Longlegs (2009).

The collaboration stuck, and three features followed: Good Time, Uncut Gems, and now Marty Supreme. The division of labor was consistent, with Bronstein primarily writing with Josh and editing with Benny.

And he did all of this while working as a freelance projectionist.

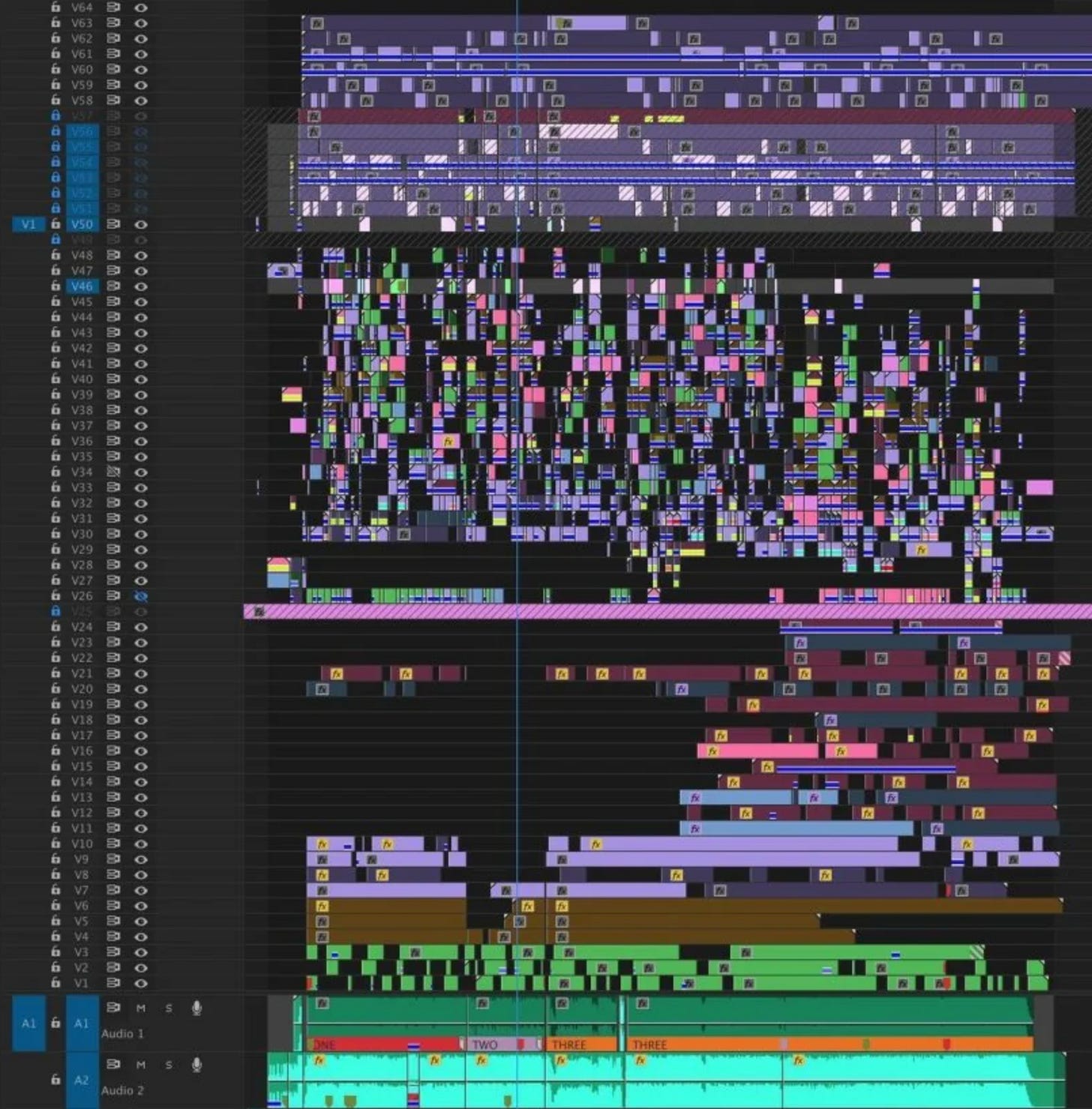

On early films, Bronstein and Benny divided up sequences and cut them separately, and only got to edit side by side starting with Uncut Gems.

Death to the Assembly

“I’ve never done an assembly in my life.”

Bronstein is a slow editor.

Josh edits the action-oriented scenes, while Bronstein handles dialogue.

He doesn’t assemble rough cuts and only shows Josh material when it’s finished. And crucially: he never makes an assembly cut. They start with the first scene and build forward, ignoring the script entirely.

The reason is structural. Once you escape low-budget purgatory, scenes are shot out of sequence. Which means assemblies built during production are also constructed out of sequence.

For Bronstein, editing is liberating precisely because there’s no obligation to honor the script, even if he wrote it.

Traditional assistants building assemblies lack this freedom. They only have the screenplay as their reference and can’t deviate from it.

Bronstein can.

Death to Dailies

“We don’t even watch dailies. When you’re shooting it’s almost like dreaming in real time and you don’t want to get woken up”

What Bronstein is describing is something closer to the Soviet montage theorists like Eisenstein or Vertov: the idea that meaning doesn’t exist in the captured image, but in the collision between images during editing.

A single shot in dailies is meaningless.

During production, everyone on set is living inside a shared hallucination, and dailies break that spell.

Bronstein’s also describing flow state.

That zone of optimal creativity where you’re fully immersed, and operating on instinct rather than conscious deliberation.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s research on flow shows that self-consciousness is the enemy of creative momentum. The moment you step outside the work to evaluate it, you disrupt the flow as you activate the critical mind, which is useful for editing but deadly for creation.

Dreams operate similarly.

You can’t analyze a dream while you’re having it without waking yourself up. And when you wake up, your mind scrambles to put what you dreamt together into a cohesive story.

Just like an edit.

Most filmmakers watch dailies religiously because they’re terrified of getting to the edit and discovering they don’t have a movie. Bronstein leans into that unknown.

CTRL + F “Footage”

“The beauty of being both a writer and an editor is that as an editor, you don’t have to have any respect for the writer, right? You can look at the material as if it’s just a stockpile of found footage and it’s your job to first impose intentionality onto it.”

By creating distance from his own work, Bronstein can see only what the footage is, not what it was supposed to be. He doesn’t need to care how hard a shot was to get.

He just sees the image. And asks: what is this, actually?

He treats conversations as “little existential medieval duels, where you have two people with opposing viewpoints, usually with one of them humiliating the other.”

The film is rooted firmly in Marty’s viewpoint as he’s the clothesline everything hangs on. But in each exchange, Bronstein works to access the perspective of whoever Marty’s interacting with and make sure that viewpoint is felt equally.

Multiple viewpoints occupying the same space simultaneously.

Fragmenting the scene to show it from all angles at once, then reassembling it into something that feels whole but maintains the tension of conflicting perspectives.

The Irony of Scale

There’s a paradox at the heart of Bronstein’s methodology:

He can afford to reject assemblies, ignore dailies, and treat his own footage as found material because he has total control. He’s co-writer, producer, and editor. He has Josh’s complete trust. Decades of muscle memory. The luxury of time.

Most creators don’t have that luxury.

You’re working with clients who need to see progress. Teams that need alignment. Budgets that can’t support endless experimentation.

You need the assembly Bronstein refuses to make.

But here’s what you can take from his process:

The assembly doesn’t have to be prison.

Don’t let the script’s structure calcify into the only way to see your material. Don’t let the assembly editor’s choices become invisible default decisions you never question.

Treat your assembly the way Bronstein treats his footage: as raw material to interrogate, not gospel to preserve.

Never Let It Calcify

Bronstein and Josh share a neurosis: when they nail a scene, they feel “a sense of mastery over every living creature on the planet.”

They can watch it 500 times in a row with the same euphoria.

But 24 hours later, it cools off.

So their process is about never letting things cool off. Always taking what seemed perfect yesterday and saying today: “It wasn’t good enough.”

“I think a lot of the tension that people get from the work stems from that kind of panic. That the movie needs to feel alive and can never calcify.”

That’s the real lesson.

Not the specific techniques. Not whether you watch dailies or make assemblies or cut in sequence.

It’s the refusal to let your work settle. To keep interrogating it. Maintain the dream state as long as possible.

And never, ever let it calcify.

Brilliant. That Q4 marketing strategy summary for Marty Supreme is so on point, almost like an adversarial network gone rogue. You perfectly capture its "relentless and chaotic" nature. Still, the "official end" of the Safdie brothers feels so sudden. Hard to believe it's definative.